This essay is part of Morten Høi Jensen’s column European Diarist.

The Russian novelist most frequently cited in discussions of modern terrorism is surely Dostoevsky, and with good reason: His 1872 novel The Possessed (sometimes translated as Demons or The Devils) is perhaps the most searing work of fiction ever written about a group of would-be terrorists. One of the novel’s great achievements is to show us what the late Svetlana Boym called “the banality of terrorism”: Dostoevsky’s nihilists are not fiery ideologues so much as petty criminals and murderous con artists, swelling with wounded pride and bourgeois resentment.

But Dostoevsky owes a grudging debt to Ivan Turgenev, the novelist whose high-minded liberalism he mercilessly caricatured in The Possessed, and with whom he famously quarreled both in person and in writing. (In a famous retort, Dostoevsky once urged Turgenev to buy a telescope for himself in Paris so he could better examine his fellow Russians – thus echoing the popular notion that the westernized Turgenev was out of touch with Russian society). It was Turgenev, after all, who first made the figure of the nihilist a staple in Russian fiction, even if his efforts were later overshadowed by his Russian compatriot.

Though once eagerly feted abroad (he was admired by the likes of Flaubert, James, and Jacobsen), Turgenev became an object of scorn at home even during his own lifetime. Conservatives and nationalists loathed his European cosmopolitanism; radicals scorned his caution and liberalism. Above all else, it was Turgenev’s ability to sympathize with both sides of an argument that riled his critics. As Isaiah Berlin put it in his essay on Turgenev in Russian Thinkers (1978):

This clear, finely discriminating, slightly ironical vision, wholly dissimilar from the obsessed genius of Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, irritated all those who craved for primary colors, for certainty, who looked to writers for moral guidance and found none in Turgenev’s scrupulous, honest but – as it seemed to them – somewhat complacent ambivalence.

It was Dostoevsky who more intimately understood the underground mentality of Russia’s emergent revolutionaries. In Turgenev’s novels, by contrast, we feel that the author himself knows little more than we do about these contemporary characters. Turgenev would have been painfully aware of this himself; his published letters are filled with confessions of his own lack of artistic confidence. (He once complained of the “thin squeak” of his own pen compared to the “free, swift brushstrokes” of the great masters.) “I cannot bear the sky,” he once wrote to Pauline Viardot, “but life, reality, its capriciousness, randomness, its habits, its fleeting beauty…all that I adore. I—I am bound to the earth.” He had little interest in the irrational or the mystical, and so perhaps was constitutionally unable to envision the Lenins and Trotskys that would creep forth from the nihilism of Russia’s revolutionary youth. But for the same reason he longed to empathize with this youth – to “unself himself,” as V. S. Pritchett said in his aptly-titled biography of Turgenev, The Gentle Barbarian.

Turgenev had a great deal in common with the “superfluous men” of his early work — with their paralyzed levelheadedness, their ironic airs, their vacillation in the face of social and political upheaval. In On the Eve (1859), Elena Stakhova, a young woman, is pursued both by a dandyish sculptor, Shubin, and a young history student, Bersyenev. But it is Bersyenev’s friend Insarov, an enigmatic, single-minded Bulgarian revolutionary intent on liberating his country from the Turks, who eventually wins Elena’s heart. No one sounds more like Turgenev than Shubin when he reflects to Bersyenev:

We haven’t got anyone among us, no real people, wherever you look. It’s all either minnows and mice and little Hamlets feeding on themselves in ignorance and dark obscurity, or braggarts throwing their weight about, wasting time and breath and blowing their own trumpets. Or else there’s the other kind, always studying themselves in disgusting detail, feeling their pulses with every sensation that they experience and then reporting to themselves: “That’s how I feel, and that’s what I think.” What a useful, sensible sort of occupation. No, if we’d had some proper people among us, that girl, that sensitive spirit, wouldn’t have left us, she wouldn’t have slipped out of our hands like a fish into the water. Why is it, Uvar Ivanovich? When is our time coming? When are we going to produce some real people?

Turgenev’s interest in and attraction to these “real people” culminated in the creation of Bazarov, the young nihilist in Fathers and Sons (1862), Turgenev’s greatest novel. Bazarov, a medical student, arrives with his friend Arkady in the latter’s home in a Russian province, where they spend a few weeks with Arkady’s Anglophile uncle and widowed father. Bazarov’s radical views scandalize everyone, especially Arkady’s uncle:

‘You reject everything?’

‘Everything.’

‘What? Not just art, poetry… but also… I hardly dare say it.’

‘Everything,’ Bazarov repeated with an air of ineffable calm.

Pavel Petrovich stared at him. He hadn’t expected that answer, and Arkady even went red from pleasure.

‘Come now,’ said Nikolay Petrovich. ‘You reject everything, or more precisely, you destroy everything… But one must also build.’

‘That’s not our concern… First one must clear the ground.’

There is something of the embryonic terrorist in Bazarov, even if, as many critics have argued, Turgenev’s portrait gradually loses some of its sting and grows a little misty with affection. Though Bazarov never acts on his radical ideas and eventually dies of blood-poisoning (which he accidentally contracts during a routine autopsy), Fathers and Sons provoked an outcry on its publication. Critics on the Left accused Turgenev of mocking would-be revolutionaries, while critics on the Right accused him of glorifying them. Others were merely exasperated by what they regarded as the author’s maddening ambivalence. As one character says to another in The Possessed: “I don’t understand Turgenev. His Bazarov is some sort of false character, who doesn’t exist at all; they were the first to reject him as having no resemblance to anything. This Bazarov is some vague mixture of Nozdryov and Byron…”

Turgenev was better at writing around Bazarov than into him. The novel’s true pathos lies in its portrayal of the people directly affected by Bazarov’s actions and ideas, in particular his God-fearing parents. When Bazarov returns home for the second time in the novel his parents, movingly, bicker about how best to keep from annoying him:

‘Mother,’ he said to her, ‘on Yenyusha’s [Bazaraov’s] first visit we got on his nerves a bit. Now we must be wiser.’ Arina Vlasyevna agreed with her husband but she didn’t gain much from this because she only saw her son at table and was completely scared of talking to him. ‘Yenyushenka!’ she would say – and he would hardly have time turn around before she was fiddling with the strings of her bag and mumbling, ‘Nothing, it’s nothing, I was just…’ Then she would turn to Vasily Ivanovich and say to him, resting her cheek on her hand, ‘How can we find out, dear, what Yenyusha would like for dinner today, cabbage soup or borshch?’ ‘Why don’t you ask him yourself?’ ‘But I’ll get on his nerves!’

I thought of this exchange last year when I saw the father of Ahmad Khan Rahami, the accused New York and New Jersey bomber, explaining on TV that he had reported his son to the FBI as early as 2014. And when I read of Sal Shafi, a Silicon Valley executive who alerted authorities to his son’s radicalism last July. There probably are many such instances in which parents realize with horror that their children have embraced some destructive or even murderous ideology, whether religious or political. In Fathers and Sons, Turgenev brilliantly lays bare such generational divides and tensions, the ideological struggles between parents and their children. In doing so he reminds us, in Isaiah Berlin’s words, that “acts, ideas, art, literature [are] expressions of individuals, not of objective forces of which the actors or thinkers [are] merely the embodiment.” There is nothing mystical or demonic about embracing dangerous ideas; they are existential choices, not spirits plucked from the sky. For every Bazarov there is also an Arkady, who abandons nihilism and embraces life instead.

Morten Høi Jensen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He has contributed to the Los Angeles Review of Books, Salon, and The New Republic, and is the author of a forthcoming biography, A Difficult Death: The Life and Work of Jens Peter Jacobsen, due out from Yale University Press in the fall of 2017.

Photo: Morten Høi Jensen, Private

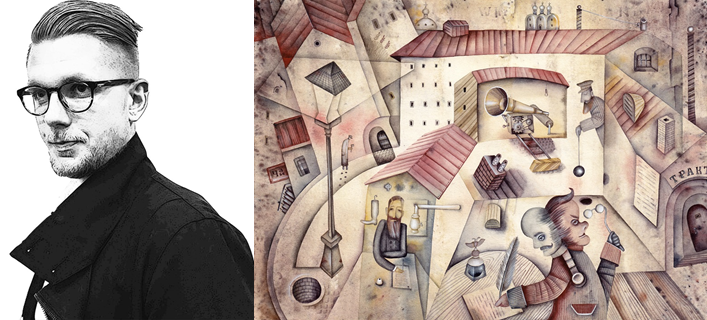

Photo: Dostoyevsky and allegory of Russian imperia, Eugene Ivanov | Shutterstock

Published on June 6, 2017.