Translated from the Danish by James McFarlane and Kathleen McFarlane.

On a calm winter morning, on 4th January, 1761, a company of five men, clad for a journey, were rowed out from the Tollbooth into the shipping roads off Copenhagen. As they stood in the boat with their back towards the sun, they could see the city lying within. The little cosmopolitan capital, with the elegant district round Eigtved’s brand-new Palace of Amalienborg, receded slowly into the distance in the thin January light. Before them in the sun lay the naval vessel Greenland. Screwing up their eyes against the glare, they could see the masts and the rigging; and perhaps one or another of them experienced a slight feeling of unease at the sight of that black silhouette. In the months to come the ship lying there was to take them on a long journey, first to the north round Skagen, then down through the Mediterranean to Constantinople. From there they were to continue their journey to Alexandria, Cairo and Suez; then on still farther through the Red Sea and down to the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, to the miraculous land of frankincense, myrrh and balsam, to that paradise on earth which the young Alexander dreamed of conquering, but where nobody had ever been, not even the young Alexander, and which-perhaps precisely because nobody had ever been there-had from very earliest times been called Arabia Felix “Happy Arabia.”

The five men in the rowing-boat also used in their documents the terms “L’ Arabie heureuse” and “Das gluckliche Arabien.” Only two members of the group were Danish; two others were German and one a Swede. All were still young, the eldest being barely thirty-four and the youngest just twenty-eight. For several years they were to live exclusively in one another’s company; but at this particular time none of them had known any of the others for more than a few weeks. Probably they were silent as they stood there in the rowing-boat, looking out towards the ship. They were bound for “Happy Arabia,” but none of them seemed particularly happy at the thought. The distant and unfamiliar has its fascination; but the day one surrenders to it, one generally finds that it has also its threatening side. This is one aspect of the matter, and something about which we can only speculate. Regarding the other and possibly graver cause of their silence during the opening minutes of the expedition, there is no need to rely on conjecture. It was, unfortunately, already an established fact. For various reasons, this little group was riven by bitter dissension.

This state of affairs, however, had not leaked out to the Press. When, a week later, on 12th January, 1761, the front page of the Copenhagen Post (Kiubenhavnske Danske Posttidende) carried the news, the announcement ran as follows:

“As His Majesty, despite the heavy cares of government in these evil times, strives indefatigably for the furtherance of knowledge and of science and for the greater glory of his people, he has dispatched a few days ago by the vessel Greenland a group of scholars, who will travel by way of the Mediterranean to Constantinople, and thence through Egypt to Arabia Felix, and subsequently return by way of Syria to Europe; they will on all occasions seek to make new discoveries and observations for the benefit of scholarship, and will also collect and dispatch hither valuable Oriental manuscripts, together with other specimens and rarities of the East. The company consists of the following persons: I. Professor Friedrich Christian von Haven, Philologus; 2. Professor Peter Forsskal, Physicus and Botanicus; 3. Engineer-Lieutenant Carsten Niebuhr, Mathematicus and Astronomus; 4. Dr. Christian Carl Kramer, Medicus and Physicus; and 5. Herr Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind, artist and engraver. These men will remain for several years in the Orient, and as they have already spent several years in careful preparation for this undertaking, it can be confidently expected that their industry and their abilities will, with God’s blessing, have happy consequences both for the advancement of knowledge in general and for the more accurate interpretation of the Holy Scriptures in particular.”

It was with these great expectations that the Danish expedition to Arabia set out. It was the first large-scale expedition that Denmark had ever dispatched, and it was the first from any country in the world to be sent to Arabia. Even in its own day, therefore, the Danish expedition aroused great interest. All Europe, eager as it was for knowledge in that Age of Enlightenment, followed this audacious undertaking with the keenest attention; and scholars from all the leading universities of the Continent sent questions to the expedition’s members in the hope that they might provide answers to them in the course of their investigations in these unknown lands. For the remainder of the century this “Arabian Journey,” as it was called, was highly esteemed for the many new discoveries which it made possible, despite all its misfortunes; over a hundred years later, English explorers were referring to “Carsten Niebuhr’s expedition” with the greatest respect. Today, two hundred years after their expedition, they are almost completely forgotten.

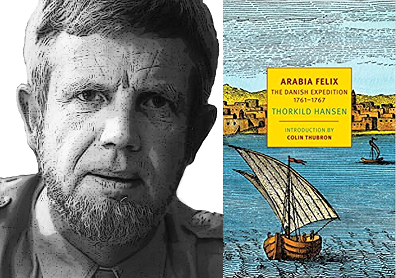

Thorkild Hansen (1927–1989) was born in Ordrup, Denmark, and studied literature at the University of Copenhagen for two years before moving to Paris in 1947. In France, Hansen supported himself by writing dispatches for the Copenhagen-based tabloid Ekstra Bladet. He returned to Denmark in 1952 and published his first full-length novel, Resten er Stilhed (The Rest Is Silence) in 1953. Hansen would go on to write more than two dozen books, many of which drew on the historical record to interrogate Denmark’s record of imperialism, including Pausesignaler (Pause Signals, 1959); Jens Munk (1965), which won the Golden Laurel Award; a trilogy about the Danish slave trade (1967–1970), the final volume of which won the Nordic Council Prize; and Processen mod Hamsun (The Case Against Hamsun, 1978). He died aboard a cruise ship in the Caribbean in 1989.

James McFarlane (1920–1999) studied modern languages at Oxford and was the first dean of the school of European studies at the University of East Anglia. Britain’s preeminent Ibsen scholar, he edited the eight-volume The Oxford Ibsen, translating a number of the books himself. He and Kathleen Crouch were married in 1944.

Kathleen McFarlane (1922–2008) was a translator and a celebrated weaver and artist from Sunderland. One of her fabric sculptures hung in Norwich Castle for thirty years.

This excerpt from Arabia Felix: The Danish Expedition 1761-1767 is published by permission of NYRB Classics. Copyright © 1962 by Thorkild Hansen & Gyldendal, Copenhagen

Translation copyright © 1964 by Wm. Collins Sons & Co., Ltd

Photo: Thorkild Hansen, Private

Published on June 6, 2017.