This is part of our special feature Facing the Anthropocene.

“Do you think we will survive climate change?”

Rori Knudtson, in Bernard’s notes on 3-1-15.

The idea of the Anthropocene has helped to focus public attention on the growing environmental problems created by fossil fuel consumption and release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. We now constantly think and talk of the prospects ahead for a planetary ecology essentially defined, not by the “natural” forces that determined the conditions of earlier ages, but by human activity. Changing weather patterns and more examples of extreme weather have become better documented and understood by scientists. But our ideas about the Anthropocene come not just from science, but also from other public discourses that interpret unfolding events. When we see images of polar bears drowning because ice flows are thawing in the arctic, or images that show the foundations of houses in Shishmaref, Alaska alarmingly tilted by melting permafrost, we are faced with how much we have changed the world we knew. In the Anthropocene, seemingly familiar landscapes become alien to us.

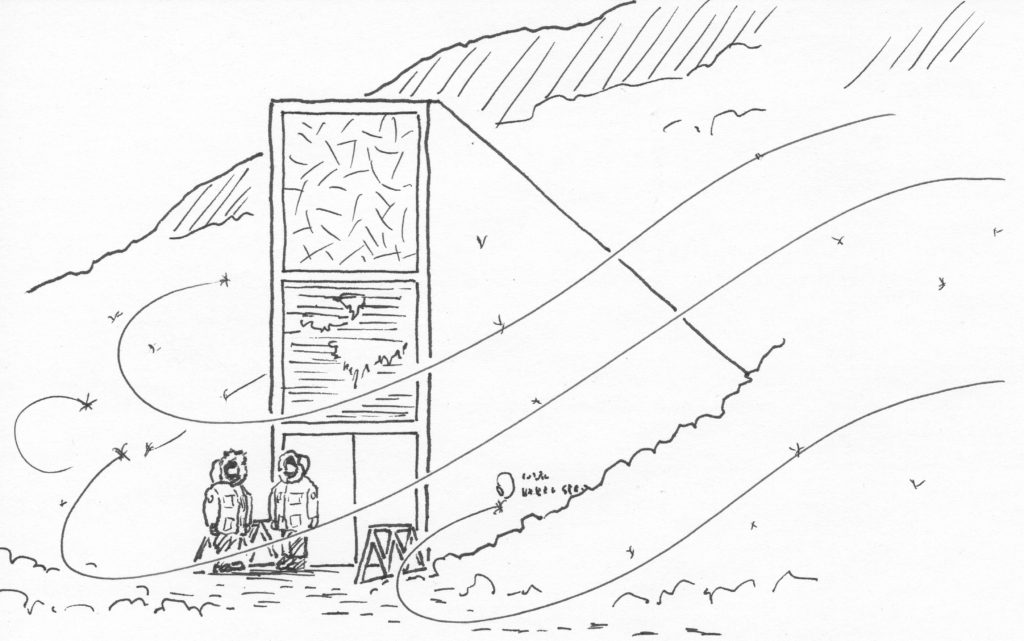

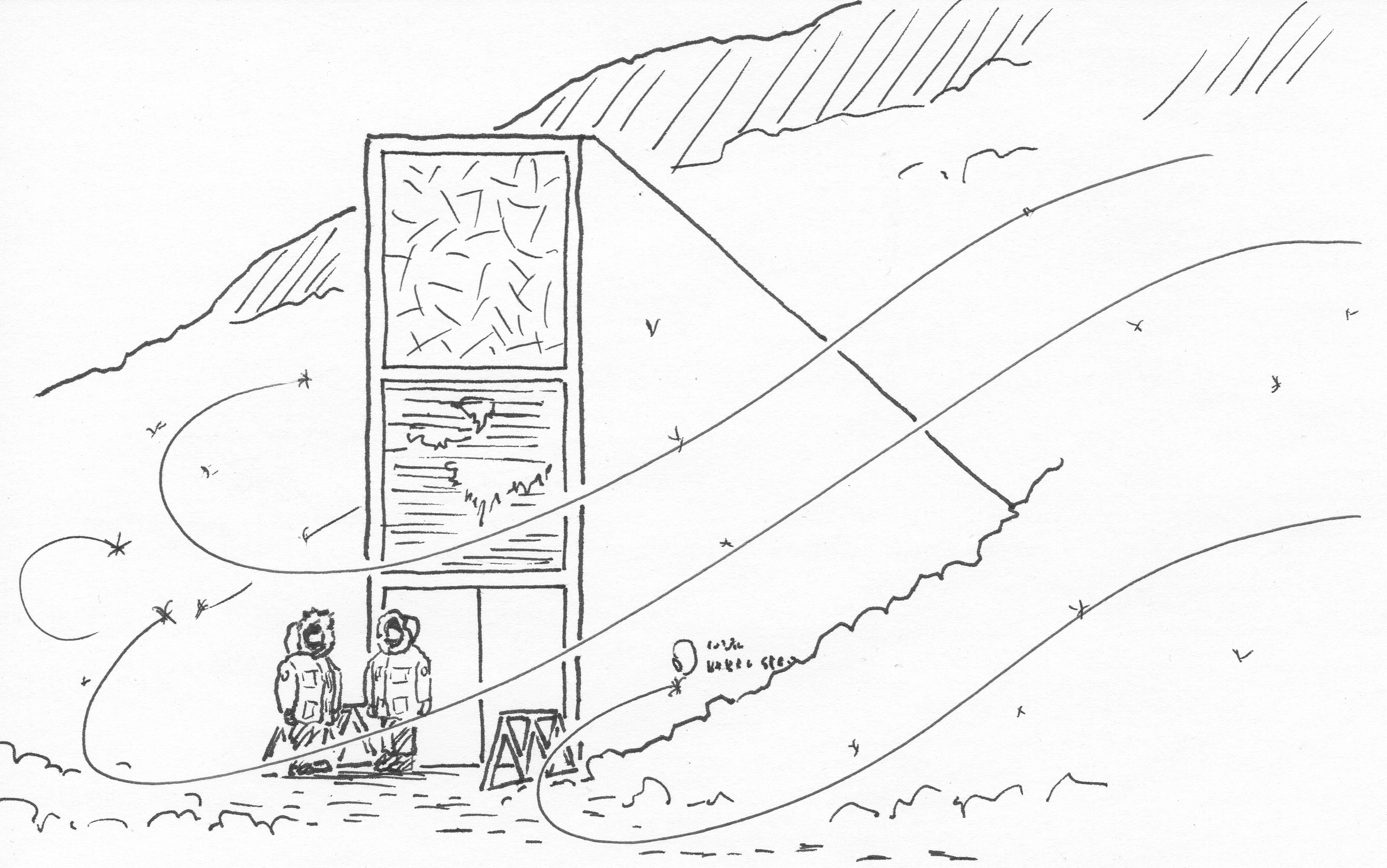

The Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Norway, is another of the places that has come to symbolize the global concerns of the Anthropocene, because observable impacts of climate change raise vital questions about the future of human food security. Farmers’ crops are at risk from unexpected droughts, floods and storms, as well as altered seasonal patterns that may see new extremes or fluctuations of heat and cold, with plant pests and diseases evolving and moving into different geographic areas. Biological diversity is also at risk, as heritage crops and crop wild relatives are lost. Agricultural scientists have long maintained seed bank stores to ensure that genetic materials are conserved for use in research, and these stores are increasingly important in the face of changing climates. The establishment of the Global Seed Vault in 2008 created a place where existing seed banks around the world can send their samples for long-term storage, in case of mechanical failures related to cold storage and humidity control, or unforeseen circumstances–from violent conflicts to budget cuts–that could threaten the samples contained in their own facilities.[i] Once described by a European politician as “a Frozen Garden of Eden”, the vault has been called a “Doomsday Vault”, a “Fort Knox of food”, a “new wave bunker” and a “Noah’s Ark of seeds” by journalists. Its founder, Cary Fowler, prefers to describe it simply as “a backup system for world agriculture.”[ii]

The considerable press received by the vault, with prestigious photo opportunities for high-level European politicians and U.N. representatives, suggests that the vault condenses a cultural imaginary that resonates with discourses about climate change and policy responses. There have already been a number of news features and two full-length documentaries produced about it.[iii] Many tourists to Svalbard are fascinated by it, although the building is not open to visitors. One recent tourism operation in Longyearbyen even attempted to offer day tours featuring the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. The website advertised:

When we drive up to the Seed Vault, you will understand that you are in a place of almost unimaginable significance. We will not enter the facility itself, since only maintenance workers and the experts handling the seeds are allowed in, but you will still feel the serenity of the location, and always carry with you the knowledge of what you have seen.[iv]

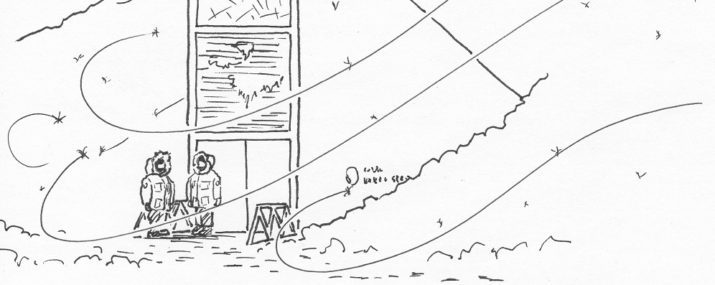

Our global concerns about the Anthropocene take root in places just like this. Tracey’s research began here in 2014, to look at efforts toward seed banking and adaptation to climate change. In 2015, she returned to Svalbard and Bernie joined her as co-ethnographer for part of the trip. The seed bank is intended as a secure facility so for most of the year, it remains completely closed to keep humidity and temperature regulated. In order to enter during the brief period when seed accessions are accepted, a number of permissions must be given. However, in the interests of transparency, those responsible for managing the vault have been generous to allow limited access to some journalists, artists and social scientists in addition to those who accompany the seed deposits.

The taxicab driver drove my wife and I along the switchback road half way up the mountain to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. The vault looked like a wedge of concrete. Its luminous beacon announcing its presence buried into the mountainside. As the taxicab approached along the narrow road to the small parking area the driver asked us again if we were sure someone was going to let us in. We assured him that we were on time and someone would let us in. We clumsily got out of the taxicab in our artic survival boots, pants, and coats. We went to the metal double-doors and watched the taxicab turn around and make its way back to town. The wind was harsh and it was whipping the snow into swirls forcing some ice particle to pass through our wolf-fur hoods prickling our skins like so many needles.

As we waited outside the vault I looked out over the bay to see the discomforting sight of open water in the middle of February. My personal bodily response to the cold would have suggested that it was bitterly cold but the open water free of ice suggested that something was amiss. As I fought the cold winds and observed the open water the double-doors to the vault behind me made me realize I was experiencing the crucial idea behind the Anthropocene. Despite the cold, it was too warm for the bay to ice over. Evidence of global warming was in front of me and the backup system to ensure the survival of the human crop heritage through the catastrophies of climate change was behind me. The Anthropocene was no longer an abstraction. This was no longer a science fiction moment; it was science fact.

(Bernard’s reflections of 3-1-15)

It’s cold!

It’s windy!

It’s amazing!

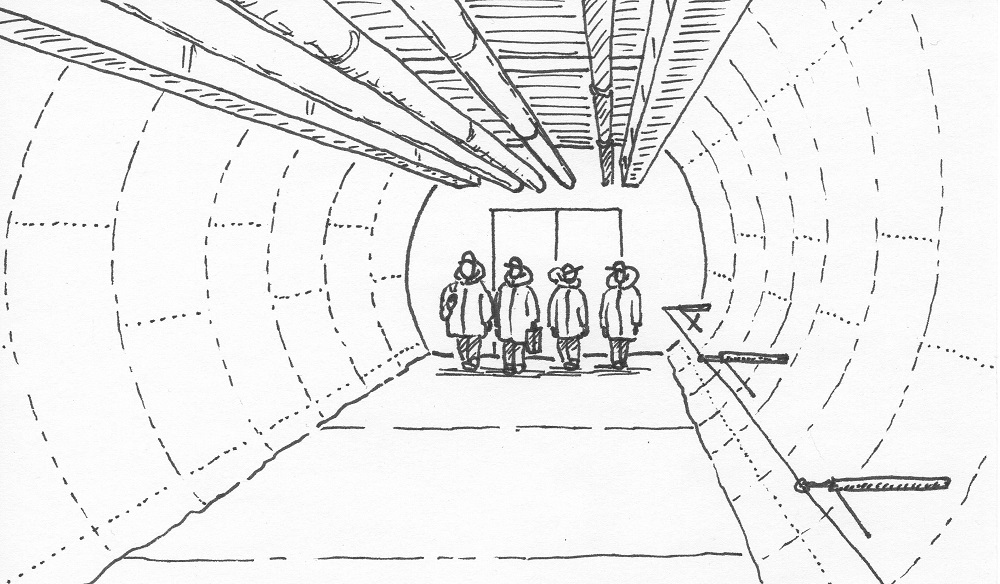

Somebody lets us in. There are two sets of doors, then a long hall descending toward the antechamber to the vault. We go into a small office to the side, where members of an HBO film crew were trying to warm their feet.(Bernard’s notes on 3-1-15)

We found ourselves suddenly in the midst of unexpected cultural ferment. There were two film crews ahead of us in the queue to enter the vault with Cary Fowler, and we spent time in the antechamber talking with Hannes Dempewolf and Brian Lainoff from the Global Crop Diversity Trust, the organization that facilitates the work of seed banks around the world and coordinates accessions for the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Before long, Rori Knudtson came over and introduced herself. She is a former academic now making her way as a creative artist and filmmaker. She took advantage of her time inside the vault to record interviews with others who were there, so we were all asked to comment on her questions about the future of the world and solutions to climate change. She was working with an expert photographer/videographer who arrived dressed in sealskin and fully prepared for the arctic temperature of -18 degrees Celsius inside the vault. We were all glad of our parkas.

Rori comes back and says she needs our help for a film project. We were supposed to be the four last people coming to the vault to save the world! We had to walk up the long passage and walk back. We had to be serious on the way back down. Tracey couldn’t stop laughing so we had to do it over. We were serious as we pondered how to save the world.

(Bernard’s notes on 3-1-15)

So, two anthropologists are standing in an interior corridor of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, talking with staff members of the Global Crop Diversity Trust. We are watching as a documentary team films Cary Fowler opening the door to the inner sanctum of the seed vault– the storage room that I like to think of as the “ovary”– again and again. Apparently he needs practice.

Another film maker, also waiting her turn to see and film inside, comes over to us and says, “I am working on an animated science fiction film where three men and a woman journey to the vault to retrieve the seeds after a cataclysmic event, so they can restart agriculture. And I need to film three men and a woman walking down the corridor toward the vault so I can model the animation on it. And I looked over and there you were.”

So we asked her more about her project. She said “the main character is a woman from Africa, like Wangari Mathaai, but with all the knowledge of Cary Fowler.”

(Tracey’s notes on 3-1-15)

Hannes and Brian were good sports through all of this. As they walked up the long corridor at Rori’s direction, Hannes told Tracey about the dissertation project he recently finished in Niger, studying the evolutionary history of an important African oil seed crop related to the sunflower. Meanwhile, Bernie spoke with Brian about heritage seeds and Native American contributions to global biodiversity resources. These conversations helped make our different individual and disciplinary perspectives mutually intelligible. There was much to learn on all sides, for the natural and social sciences are engaged with research and policy debates around the world, working on the big challenges to food security in the Anthropocene. Yet these exchanges were playfully framed by our shared participation in Rori Knudtson’s vision of the future. She drew on a social imaginary that recognized science must have some role in “restarting” world agriculture in the event of system failure, but she couldn’t quite imagine what kind of assistance that would be. For her, it was all contained inside the vault itself. Her visit to Svalbard was the germ of several ongoing artistic projects related to film and storytelling. The images captured by her team at Longyearbyen, and inside the seed vault feature prominently on a website called “The Infinite Seed”.[v] Her science fiction movie called Spire is still a work in progress. A thumbnail for it teases: “In a post-apocalyptic world, the fate of human survival lies with an agriculturist and the remaining crew of a reconnaissance mission to the edge of the world.”

The inclination to narratives about desperate catastrophe and survival marks so many stories in and about the Anthropocene, and this is perhaps why the Global Seed Vault, with its robust and evocative architectural design, has caught the fantasy of storytellers like Rori. Science fiction plots drastically simplify the nature of the crises we face. They also abridge the slow process of regenerating seed from the tiny samples that are stored in seed banks, which must be multiplied through a series of “grow-outs” before there would be enough seed for use in research studies, let alone replanting fields for food crops. “Restarting agriculture” after nuclear war or other disaster of global proportions would not be so easy, particularly if soils, groundwater, and climate conditions were rendered inhospitable. But the real story of climate change is already challenging on a day-to-day basis for many marginal farmers. Research that explores how to breed crops that are more resistant to heat and drought, for example, depends on not just the seeds themselves, but also on our understanding of the origins of crop domestication, and extensive knowledge about the kinds of plant crosses that can bring new vigor. The Global Seed Vault is extremely important as an extra level of conservation for heritage seeds, however, the vault does not work in isolation. Rather, it is simply a nodal point in a global system of “living” seed banks that now work together to keep seed collections viable and support research to maximize farmers’ resilience to changing climates. This system of ex-situ conservation is, in turn, only one facet of the efforts essential to safeguarding the plant genetic resources needed for food and agriculture in the future, since a fair amount of the world’s biodiversity is still safeguarded directly by small farmers, gardeners and traditional keepers, many of them in out-of-the-way places. Their cultural knowledges and visions, and capacities to maintain livelihoods are also germane to the future.

As the HBO crew came out to take a break from the cold, Cary Fowler invited Rori, the photographer, Tracey and Bernie to come in and see the -18 degrees celsius vault together. Hannes joined us.

Quick entry into the antechamber, quick entry into the vault. We can’t let warm air into the vault. Once in the vault and aclimating to the drop in temerature, I asked Hannes a hypothetical question about access to seeds. Let’s say a Guatemalan village had cultivated a distinct variety of cacao and gave a variety to the national seed bank. The national seed bank deposits a variety in the Svalbard bank. If the village suffers some kind of catastrophe, and the variety is wiped out, do they go to the national bank?

Can they request and obtain seeds from the vault?

Hannes responds, “No. Only the depositor can withdraw the seeds”.

Hannes’s nose is very red and he was trying to keep it from freezing.

Then the lights went out (so that’s what the inside of a refrigerator looks when the door is closed)! Cary left to go reset the switch. He came back to show us shelf after shelf of acquisitions. We are shown a cardboard box from Canada (because we’re from Canada?). We are shown plastic boxes for new acquisitions; a wooden box from North Korea. Many shelves with boxes and boxes; cardboard, wooden, and plastic. All the later shelves were filled with plastic boxes . It’s a work in progress… HBO is ready for Cary again. We leave the vault and tell him how inspirational the vault is. I tell him it’s not a vault but a cathedral. Cary agrees.

(Bernard’s notes on 3-1-15)

The HBO film crew’s work at the seed vault the day that we visited emerged as part of a series called VICE, in an episode dedicated to “Savior Seeds”.[vi] It assumed a critical perspective on genetically modified and patented seeds, particularly the impact of Monsanto’s soybeans in Paraguay. There are no GM seeds kept at Svalbard, so the vault segment of this episode was intended “to see what’s truly at stake when humans try to improve on nature”. Because the complexity of this story is limited by the length of the television segment, the narrative merely outlines a familiar argument against agro-industrial profiteering. Once again, pictures of the vault stand in for a much larger field of important debate about property rights and the fate of biocultural heritage.[vii] But the heritage seeds kept at Svalbard are considered a global public resource under the terms of an international agreement called the Plant Treaty.[viii] This “multi-lateral system” is a framework that is still the subject of negotiation related to national sovereignty and benefit sharing. Agricultural scientists argue that the plant genetic evolution of staple food crops represent complex geographic diasporas, and all countries are dependent on each other’s genetic resources. While there is much to be questioned about how private corporations are allowed to benefit from public resources in order to develop patentable materials, other agricultural research and extension funded by and for the public good depends upon these resources too.

Sharing genetic resources from existing seed collections with the communities where they were historically collected suggests a significant commitment to work together on the challenges of the twenty-first century. There are a growing number of community organizations that celebrate their own participation in seed banking projects and even deposits at Svalbard. The late environmental activist Wangari Maathai, founder of Kenya’s Greenbelt Movement, in fact collaborated with Cary Fowler and accompanied the very first group of rice seed deposits from her country to the Global Seed Vault in 2008. Another example is Peru’s “Potato Park”, an initiative that celebrates indigenous Andean heritage in collaboration with research and conservation at the International Potato Center.[ix] According to social activist and plant scientist Alejandro Argumedo of Associación ANDES-IIED:

“The farming practices here in Peru are interwoven with our cultural rituals and practices. Our potatoes are therefore both a cultural and a biological legacy. Sending this collection to Svalbard is like sending our family members to a distant place for safekeeping, in case the rest of us need to be rescued by them in the future.”[x]

As ethnographers, we are committed to understanding the Anthropocene as an everyday object of cultural imagination. This is not simply a homogenous global Zeitgeist. Instead, we see the cultural imagination of the Anthropocene as a series of multiple, fragmentary and overlapping stories about the past, present and future of the world. Like the “dreamings” that embody the deep time historical experience and ontological understandings of Aboriginal Australians, the allegories of climate change are deeply rooted in particular landscapes. Svalbard is one of these places. The Global Seed Vault excites the imagination because it is a liminal space where the material substance of biodiversity—our seed heritage— returns to a state of seemingly infinite potential. However we perceive the eventualities that might unlock that potential, such places offer us resilience against the burgeoning disorder of species loss and the fateful temporality of extinctions. Highlighting illusions of endless resources and endless development that underpin late capitalism, places like the Global Seed Vault nevertheless rescue modernity from forbidding chaos, and give us hope. In our own fieldnotes from Svalbard, we found evidence of how it had inspired us. Like Rori, we think that storytelling is profoundly important. Like Hannes and Brian, we think that we need to keep learning in order to do it.

Rori: “What would you create to help us survive climate change?”

Tracey: “A great public university! And I would fund it.”

Berne: “Institutions to share ideas, be they universities or community centers. I would build opportunities for conversations… beyond disciplinary boundaries…”

Rori: “Do you think we will survive climate change?”

Bernie: “I am an optimist. Yes… I am Native American and we survived 500 years of colonialism and globalization. If we can look forward with responsibility and respect, seven generations to the future, we can do it. I understand that the sentiment ‘all my relations’ includes language, culture and landscape. We expand our responsibilities to include our environment as part of our kinship. Indigenous knowledge is not just for indigenous peoples, it’s for our mutual survival.”

Tracey Heatherington is a cultural anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Her ethnographic project, “The Lively Commons: Seed Banking and Adaptation to Climate Change,” was funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. This research tracks global gene banking initiatives across scales and networks of collaboration, connected through the node of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Her contribution to this essay was informed by research at the Global Crop Diversity Trust, and discussions at a panel on “The Anthropocene on Tour” at the Annual Meetings of the American Association of Geographers in 2017.

Bernard C. Perley is a linguistic anthropologist, visual ethnographer and member of Tobique First Nation in eastern Canada. He currently teaches at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, and has been a Visiting Professor at Cornell University as well as Dartmouth College. He is a core member of the Working Group on Language and Social Justice of the Society for Linguistic Anthropology and recently served on the Executive Board of the American Anthropological Association. His “Going Native” political cartoons are published regularly in Anthropology News. His ongoing research and advocacy in language revitalization explores metaphors, cognition, agency, and emergent subjectivity in Native North America.

Sketches used with the permission of the artist Bernard C. Perley

The images presented here are not transferrable to any THIRD PARTY, and are not to be printed, published or used in any way for any other article, publication or marketing event without prior written consent/agreement.

References:

[i] See https://www.croptrust.org.

[ii] Cary Fowler 2016. Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault. Prospecta Press.

[iii] “A Visit to the Doomsday Vault.” Correspondent Scott Pelley, 60 minutes. Originally aired March 20, 2008 on CBS News; Seeds of Time. Directed by Sandy McLeod. New York: Hungry, 2014. 77 minutes; Seed Battles. Directed by Kees Brouwer. Brooklyn: Icarus Films, 2014. 50 minutes.

[iv] See http://www.visitsvalbard.com/?id=1978073830

[v] See http://www.theinfiniteseed.org

[vi] “Savior Seeds.” Correspondent Isobel Yeung, Vice, S3 E9. Originally aired May 8, 2015 on HBO.

[vii] See for example Kregg Hetherington 2013. “Beans Before the Law: Knowledge Practices, Responsibility, and the Paraguayan Soy Boom.” Cultural Anthropology 28 (1): 65–85.

[viii] International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture 2004. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Text available at http://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/en/.

[ix] See Virginia D. Nazarea 2013. “Temptation to Hope: From the ‘Idea’ to the Milieu of Biodiversity”. In Nazarea, Rhoades and Andrews-Swann, eds., Seeds of Resistance, Seeds of Hope: Place and Agency in the Conservation of Biodiversity. University of Arizona Press.

[x] “Indigenous Communities from Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas to Send Some 1,500 Potato Varieties to Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Arctic Circle”. Crop Trust Press Release February 15, 2011, https://www.croptrust.org/press-release/sacred-valley-incas-send-potatoes-seed-vault.

Published on May 2, 2017