Translated from the Slovak by Janet Livingstone

A strange boy joined Elza on her way home. By chance. Their strides coming into sync. It was the last day of August and the next day he’d have to go back to school again. When he smiled at her, she offered him a cigarette. She shouldn’t have. She saw this when he tore a Coca-Cola can into strips with his bare hands. The boy explained that he wanted to study low-voltage but his assholeparents were making him study high-voltage at school. Finally, Elza overcame her cowardice and said good-bye. The stranger still managed to bite her in the neck.

Ian was already in his pajamas. he poured her a whisky as dis- infection. She called Rebeka. Listened to her voice as it ran through her body. It warmed her.

In bed Ian read Elza a story about jackals. In the story they claimed to be powerless. That they could express good and evil only through their teeth. “That’s odd,” said Elza. “Recently a strange boy bit my Friend in the neck on the street.”

“When you left, I sat in the car. I couldn’t go home. Then I drove there—the long way, down your street,” said Kalisto, hug- ging Elza tightly around her wounded neck.

“Every day, everything I do—is just a dance to meet you half- way,” said Elza, smiling with her teeth pressed against Kalisto’s mouth. Behind his back a brown current of water was reflected in her eyes. It was autumn. The Danube was rising.

In the evening, Rebeka and Elza sat alone in the café. They slowly sipped from a common glass of wine. Rebeka was already clearly drunk.

“God Rebeka, you get drunk from one glass of wine,” moaned Elza.

“Don’t be stupid. You’re making me into an alcoholic who gets drunk from one glass. Actually, I have a whole bottle of Calvados in my purse. Don’t worry, I start drinking first thing in the morning. I drink and stroll along the quay.”

Ian sat at the table eating dinner. his dumplings first slipped into the water and then turned to stone. When Elza lied, Ian’s face froze. She remembered a card, which Jehovah’s Witnesses carry with them in case of an accident. Instructions to the doctor: no blood!

______

The Danube was rising again. People stopped going to work, they just walked along the river instead. It was coming up closer and closer to their faces. They stopped noticing the buildings and mirrors—some left their families so that they could walk all day along the river, which was getting closer and closer to them day after day. It was coming up to meet them. Its humid, pulsing breath beat in their heads at night. It stung. They sucked it deep into their lungs. Swayed lightly while they watched its ferocious current.

Elza sits alone in the café. Rebeka didn’t come. Something came up. (Probably Yp and the very small and fast dog.) “What should I do if I love two men?” a young woman asked her girlfriend helplessly at the next table. “Write a novel,” said Elza turning toward her. “Make it a story where there’s little talk and a lot of sorrow.”

The river draws closer and closer to the stream of gawking people. They jump onto the sandbags so they can see themselves in it. And at night they dream dreams on the shore. Dreams in which clouds of dust whirl behind herds of galloping animals.

“My knees hurt so much that I can’t even hold the slimmest woman on my lap. Or a child. Nothing. I can’t even put a thicker book on my knees. Only a newspaper. And my joints! And soul! And that weirdness! I see it in myself—I’m weirder and weirder every day. I used to be happy and all. But now I’m just sort of weird. Constantly. Today, though, I felt like working again. That morning air, morning sun and morning cognac were really good for me. Today I’ll be going around in circles until evening,” said Kalisto Tanzi, laughing.

In twelve hours, he would hug Elza with his arm around her shoulders. After midnight he always drives with only one hand. Elza explains the feeling of whoooosh.

“When I drive down heyduk Street and someone runs out of the dental surgery with a handkerchief pressed to their cheek instead of a phone, I feel sorry for them and hug them in my mind. In reality, though, I actually just miss them, I lean back until there’s that quiet swoosh and I think to myself—whooooosh, I’ve avoided it so far. All that pain and suffering. Whooooosh, and I breathe a sigh of relief that I’m not in their shoes.”

“I do it in waiting areas. I thread my way through people avoiding them only by a hair. I swish by, stirring up the air and sighing with every stem christie: whoooosh… I dodge, even if the contours are clear in the distance. I feel like I’m dancing, twirling toward them.

Rebeka’s gaze couldn’t be avoided. “I saw it in you. The change. Your face is different and you’ve stopped eating. You can barely move your arm. As if it were wedged somewhere independently of your body,” said Rebeka to Elza on the phone. “You sniff out everything,” Elza jumped in, panicking. “I just feel sorry for Ian and actually for you. Actually for everyone. I pity all of you. You should get a job instead.”

Whoooosh—thought Elza to herself. In the dark, Kalisto Tanzi’s car barely missed Ian’s body.

Ian was walking toward the quay. He recognized Rebeka’s back from a distance. She was standing right at the flood wall.

Intensely watching the surface of the river. It seemed like an endless straight line. Rebeka inhaled deeply, as if together with the humid night air she wanted to take in the time zone of the quay as well. Time here passed differently than on the tennis court, differently than for people in cars, and had a completely different tempo than at the hospital above the river. There the hands of the clock move like a magnetized needle in a compass. Motionless for years, it turns constantly. Rebeka and Ian nod- ded to each other, and Ian walked on. he moved slowly. As if he were carrying in his body the right, unique, but very fragile constellation, which he didn’t want to disturb. So that the images didn’t mix with one another. he breathed shallowly, avoiding exertion, walking up hills or sudden movements. As if he had a lottery bin in his belly. Numbered balls, that weren’t allowed to move from their places, or touch each other, Rebeka thought to herself about Ian’s innards.

Kalisto Tanzi knelt at Elza’s feet and kissed her pants. She looked at the crown of the head of a man who liked fabric. he loved fully-dressed women. They sat for months in the car. Submerging their faces in each other’s sweaters and hair. Kalisto basically never wanted to go to an apartment, to bed.

For the first time, we took off all our clothes. Kalisto Tanzi said: “I feel so relaxed! Now I’ve got everything in the world.”

She knew they were in trouble. It was a lovely view, watching him lie down naked on his back. he put his legs in the exact position a baby does when you change its diaper. A defenseless position. Despite this, she diligently searched the white body of the minotaur. But found nothing she desired.

She stroked his back. Slowly and tenderly. More with wonder than love. With wonder at how she had loved this body so much that she’d held on for hours in the snow in the parking lot waiting for it. how for this she had lost her mind for a whole winter and summer and had pressed her face into the dirt in the garden. In the car Kalisto Tanzi regained his balance. he left the motor running even in the parking lot, ran the heater and won- dered out loud why the quality of Tom and Jerry’s performances had gone down over the last few years and whether they were now performing without joy, just for money.

Elza. The windshield shattered and the glass flew into our faces. And one of the smaller windows exploded too. Then Ian stepped back from the car and song&dance gradually moved away.

It was precisely this, which evoked the biggest confusion and terror in me—stellar, endless, universal terror. The idea that it would end with Kalisto Tanzi and I holding hands in the car and talking and suddenly, all at once, the only thing left of him would be a leg and a hand and I would see into his belly. And then I didn’t know what would be more terrifying—that he no longer existed or the thing he had turned into. All those tangled tubes, utility networks—soft and flexible like slimy vacuum hoses, pipes in the ugliest parts of houses, in the neglected base- ments of hospitals—the ones that made me stop smoking. On them you could smell those cigarettes that pregnant women and dying old men had gone there to smoke secretly. They smelled helpless, like blood—metallic.

Like that heavy, gray table I’m sitting at a week later with Kalisto Tanzi drinking fragrant Metaxa. One after the other like Alice drinking her potion, but it’s completely useless, because I don’t feel like sticking my hands under Kalisto’s shirt or in his pants, and he feels it, and a helpless smile is spreading to the corners of his face. Wider and wider.

And he’s ordering cognac and one bowl of soup after another and the table between us is shaking like his legs down under the deck, like Kalisto’s helpless tied-up-in-knots stomach. And I see myself a couple of months before starting to shake when I saw his shirt hanging over my chair. And my body didn’t exist when he wasn’t looking at it.

The river was back in its bed again. On the banks, mud-combed grass was drying. The stone with the poked out eyes that had just hurtled through the window fell back onto the bottom of Kalisto’s car. That’s probably all that remained after the flood.

Yp sat on the wall. Stroking a very small and fast dog.

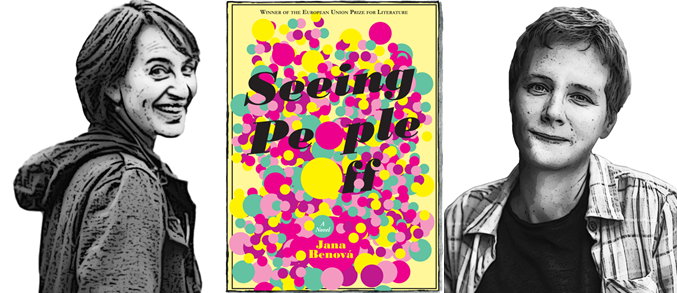

Jana Beňová is one of the most acclaimed Slovak authors, and the winner of the European Union Prize for Literature. She is a poet and novelist, author of the novels Seeing People Off, Get Off! Get Off!, Parker, and Honeymoon (forthcoming from Two Dollar Radio), as well as three collections of poems. Though her work has been widely translated throughout Europe, Seeing People Off is her English-language debut.

Janet Livingstone was born in Boston, Massachusetts and ventured to Czechoslovakia just after the 1989 Velvet Revolution. In total, she spent fifteen years in Bratislava in Slovakia. In 2003, she began translating films and plays from Slovak to English and hasn’t looked back since. Among her full-length book translations are Master your Stage Fright by Slovak master violinist, Bohdan Warchal and Piata loď (working title: Boat Number Five) by novelist Monika Kompaníková. In addition to Jana Beňová, her current translation projects include the novels The Best of All Worlds by Slovak-Swiss author Irena Brežná and The Arab World—Another Planet? by Emire Khidayer. Janet lives in Seattle with her two children and also speaks French, Italian, Russian, Spanish, and elementary Japanese to anyone who will listen.

This excerpt from Seeing People Off is published by permission of Two Dollar Radio. Copyright © 2017 Jana Beňová. Translation copyright © 2017 Janet Livingstone.

Photo: Jane Beňová, Vladimir Simicek

Photo: Janet Livingstone, private

Published on April 4, 2017.