Untitled Monument, 2015, Manca Bajec

I felt my chest tightening, as I was deciding whether to take my camera and recording equipment out of the boot of the car. My cameraman sat next to me quietly and I asked him whether he thought it was a good idea. He said he would rather not film but if I wanted him to he would of course do that. We got out of the car and left all our equipment inside. We made no recordings during our trip. All the texts were written from memory, while being retold to an artist who made drawings according to my descriptions.

Fragment from the work A week in August:

It was a scorching hot day and Bakira led us into the shade. There were some bricks in the corner. She picked them up and started stacking them into three piles, making little stools. She offered us a seat, took out her cigarettes and started smoking. She smoked and looked around, then started talking; first about the house, what had happened, the people that had died in there, the babies that died in there, and about how they deserve peace at least now. It was difficult at first to follow what she was saying because she looked straight into my eyes. Her light eyes looked so sad I lost my concentration. She explained that this was not a memorial but was a room for memory, a room where the pictures of the people who died in there would be placed. A room that the family could visit, a place where people could visit and never forget what had happened. She was very firm about it not being a memorial. She believed in the idea of wanting the site of the crime to remain as is, untouched.

Bakira spoke very little about her own torture and loss during the war. I knew what I had read, I knew she had been raped and beaten. I spoke and asked very little. There were so many other things that Bakira said, some I didn’t very clearly understand, some I cannot clearly remember but mainly it was my impression of her that remained. We walked back to the car, she smiled and gave me a hug.

We come to feel that these stories of rape and murder, slaughter and torture are something commonplace. We start to think of it as something that just happens. It is only when you look at some-one that has experienced it that the abstract disappears and the reality of individual suffering manifests itself.

–Manca Bajec for EuropeNow

A week in August, 2014

The question of voyeurism and victimization of narrative, as well as revisionism, often comes into question when artists are working with topics of war, conflict, and victimhood. The artist can, at first glance, appear as the abuser, but as an audience we are usually left in the dark about the artist’s real intentions and are instead presented with imagery. In the context of the contemporary, now, we are already overwhelmed with images of violence and destruction, so one could easily question the purpose of additional imagery presented in an aestheticized manner.

In the current political stasis, we return to the question of what role art should or should not have in the environment in which it exists.

The monument as a historical narrator has become an outlet for artistic practices, becoming a method of commenting on contested emblematic moments.

As an artist and researcher my work has been addressing and adapting ideas of monument building and evaluating practice as a method of writing history and counter memory, in this way questioning how the state of memorialization of conflict is dealt with.

I have invited artists Marco Godoy and Fernando Sanchez Castillo to think through some questions with me. Both artists have practices that make inquiries into the state of politics and power, and reflect on how memory and history are propagated in the present.

What we still have to talk about, 2013, Marco Godoy

EuropeNow Could you tell me a little about your work and about this work in particular?

Marco Godoy I’m interested in authority, how it is constructed and in which ways we confront it. Authority affects many levels, from the way the State functions to our personal interaction with our relatives and friends. For the last few years, I have been observing collective memory and how it plays a role in the legitimation of authority. There is the question of who benefits from the current narrations and what possibilities are available, through the use of an art practice, to bring these conflicts into the discussion.

EuropeNow What about this work?

Marco Godoy The work is a negative reproduction of one of the few remains of the Spanish civil war, a façade of a church in Barcelona that was damaged during the bombings, by Italian bomber planes, at the end of the Spanish Civil War. For 40 years, the dictatorship erased most of remains of the war so there are few buildings left that have physical ‘scars’. What I wanted to do is rescue this document and decontextualize it, but confront the physicality of a cast that is 3 meters long by 2 meters tall.

EuropeNow What do you mean by decontextualize it? Why?

Marco Godoy The obvious reason is to take it away from the context of the space in which it exists in the city and bring it into an exhibition space. I am interested in decontextualizing what the original represents, transforming the damaged wall into a ‘skin’ that resembles the original one without trying to replicate it. The surface of the original wall is too loaded. We need to get a distance from the original document.

EuropeNow Why do you think it’s important to remove it from the space? Don’t you think that the confrontation with the memory needs to take place in Spain?

Marco Godoy When dealing with conflict, the images of the conflict are attached to the constructed history or memory. There is no way that, by addressing the images and remains of the conflict, I can open up a space for dialogue to take place. The possibility of working within the sphere of artistic practice means finding areas that are distant enough so that we can renegotiate certain positions and memories. I am not interested in conversing with people that already agree with me, nothing happens when you do that.

Sant Felipe Neri Church, Marco Godoy

EuropeNow Why do you feel this work is necessary?

Marco Godoy Spain is the 2nd country in the world with most mass graves, there are about 150,000 people still buried and unidentified. If we divided that over the whole territory of Spain is more than 3 people per sq kilometer. During the last decade, the government has passed laws that promised that these graves were going to be opened but never provided funding or support so nothing has happened. The State is carefully working to maintain a particular narration of the war while the survivors of the war are still alive, once those people are gone there won’t be many left to dispute this narrative.

The work was originally produced for a show in Madrid. The physical confrontation with the remains of the war are so intense that in the context of the Spanish political situation in 2013 I had to bring it into an exhibition space. For generations older than me it was too difficult to address these topics whereas I find my generation is removed enough from the conflict to be able to start questioning whether the histories we were told did not occur in that way.

EuropeNow Tell me about why you decided to make a positive rather than a negative?

Marco Godoy It is a 1 to 1 cast, but I was not interested in making a relic. I wanted a distance from the original and not create a replica. When the volumes become a positive surface, the scars become tangible, you can touch them. The volume in positive is coming at you in a way that you cannot achieve with a negative, it is almost shooting at you.

What we still have to talk about (detail), Marco Godoy

EuropeNow I first saw this work in Whitechapel Gallery but you mentioned that you had other ideas of how to present the work?

Marco Godoy With a work like this that is specific to its context when its shown elsewhere it is difficult to adapt the narrative. The issue at Whitechapel was how to introduce the context in a group show, it was challenging but the potential of the work has more to do with how the work can be activated. I was positively surprised as the public did engage with the work, perhaps because the scars of the WWII bombings in London are still visible and the struggle against fascism is something in the collective memory of Britain. So that opened a door to talk about these issues. But I imagine that this particular work will become most activated in an educational context. For example, to talk about the Spanish civil war in front of it, to feel the surface. The work would function better in that way than just in an exhibition space. Most of the times the exhibition space is not enough, I would like to find a space in which we could talk less in ideological terms and more in empathic terms.

EuropeNow Have you ever felt like you needed to question your right to deal with certain topics that do not concern your history?

Marco Godoy Of course. When making this work I doubted whether I had the right to speak about this and I felt quite guilty. But I think that’s a trap. Because for years we were told that we should not open the wounds of history because those who have an authority on memory have made us feel that any attempt to question it shouldn’t happen. In the end we have integrated this discourse and it takes generations to counter that. It is a subtle exercise of authority, which leads to suppressing any alternative views. We need to have documents that are in exhibition spaces, so it also becomes the responsibility of cultural institutions to raise questions about these issues.

Guernica Syndrome, 2012, Fernando Castillo Sanchez

EuropeNow Fernando, can you tell me a little more about Guernica Syndrome?

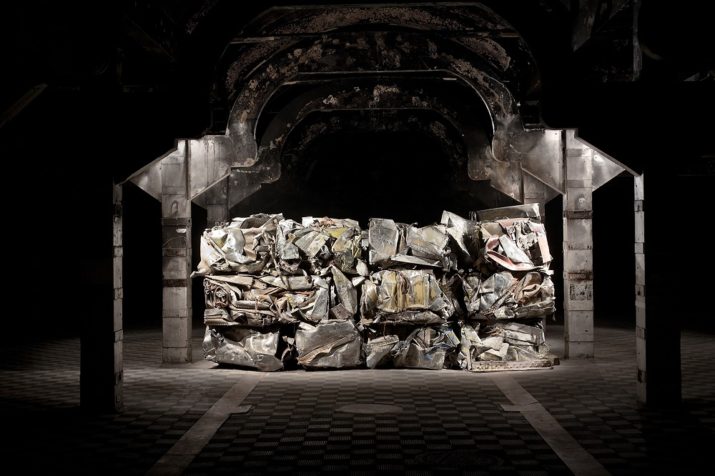

Fernando Castillo Sanchez The ‘Azor’ was the protocol army ship, built by the Bazán Shipyard, for the use and enjoyment of Spanish Head of State General Francisco Franco. Launched in 1949, the ship’s godmother was María del Carmen Franco y Polo, the dictator’s daughter. Measuring 46 meters long and 7,5 meters wide, the vessel was used as a pleasure yacht by Franco and his family. The Ship was a very useful scenario, a kind of no-where land where the dictator could have controversial meetings with people that could be compromised for visiting Spain. After Franco’s death, the ship was used in 1985 by the then Prime Minister Felipe González in a controversial Summer cruise. The press compared his behavior to that of Franco’s. In 1990 the Spanish government auctioned the ship, specifying that it must be destined only for scrapping. However, a nostalgic fascist businessman secretly bought it and tried in vain to turn it into a floating entertainment venue in the port of Marbella. The authorities rejected the idea and blocked any possibility for the continuation of the presence of the boat. The new owner decided to cut it in parts and reconstruct it in his homeland. The whole adventure led him into bankruptcy and he had to sell the entire property and to abandon the unfinished project to a group of investors. Since then, the “Azor” has rested and lost luster on the outskirts of the town of Cogollos, Burgos, becoming a tourist attraction for nostalgic and surprised visitors, 250 km away from the seashore. The whole strange destiny and the surrealistic story became a ‘hot potato’ issue in Spanish media, divided by the use of memory and public icons. It is a very popular object in the Spanish nostalgic memory of the dictator and a continuous photo opportunity for travelers. I bought it by end of 2011. It was transformed it into a prism shaped volume. The prism is exalted in minimalism for its constructive impersonality and for its lack of sentimental or emotive references. Some referential parts were preserved such as the mast, benches, signs, flag holders, and benches…. Now, as a ghost ship, Azor is looking for new ports.

Photograph by Fernando Castillo Sanchez

EuropeNow I can imagine you got quite a reaction from the public. What kind of responsibility do you feel you have as an artist dealing with such historical material?

Fernando Castillo Sanchez There was a gap that appeared between the physical remains of the ship and its abandonment to a reclining economy… It seemed that it was not working as a relic from which one could obtain an economic profit and the only value was the metal remains… there was no protection or nostalgic value instated by the owners so I could purchase and then reintroduce it as a historical object using the sphere of art strategies.

Azor ship being taken apart, Fernando Castillo Sanchez

EuropeNow What you feel the role of the monument has in your art?

Fernando Castillo Sanchez Monuments are visions and impositions of power… by subverting those points of views but using the same materials or strategies as power I act like a parallel state that shows the absurdity of the original structures.

EuropeNow How do you approach the idea of remembering or forgetting of contested histories?

Fernando Castillo Sanchez When there is a gap or a void there is a space for the synergies and the dialogic methods of contemporary art… There is nothing more interesting than the stories abandoned or forgotten, used to build up new points of views that make us more free.

Manca Bajec is an artist and researcher whose current multidisciplinary work is situated in the realm of socio-politics and space, questioning representations of violence and power. She is a PhD candidate at the Royal College of Art in London conducting research on the destruction and reconstruction of monuments. She recently completed a newly commissioned work for IoDeposito, Witness Corner Marked and has published commissioned works for Eros Press and Mnemoscape. Bajec has lectured and presented her practice internationally, and has received several grants and awards, among them the Ashley Family Foundation Award and was nominated for the ESSL Award for Emerging Artist. Bajec was born in Slovenia, grew up in the Middle East, and currently lives and works in London.

Marco Godoy is a cross disciplinary artist currently working with photography, video and installation. Born in Madrid and now living in London he is MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art, after graduating from the UCM of Madrid and School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work has been exhibited internationally in galleries and institutions such as Dallas Museum of Contemporary Art, Matadero Madrid, Centre George Pompidou, Stedelijk Museum s-Hertogenbosch, Edinburgh Art Festival, Liverpool Biennial, ICA London, Palais de Tokyo and Whitechapel Gallery.

Fernando Castillo Sanchez was born in Madrid in 1970. Degree in Fine Arts from the Universidad Complutense Madrid, MA from the Instituto de Estetica Contemporanea, Universidad Autonoma, Madrid. Former member of the Research Group of ENSBA Paris and resident at the Rijksakademie Amsterdam. Currently participating in the Research Team of the United Nations Geneva, PIMPA Memory, Politics and Art Practices.

This is part of our special feature Memory and the Politics of the Past: New Research and Innovation.

Published on April 4, 2017.