Café Neandertal: Excavating Our Past in One of Europe’s Most Ancient Places by Beebe Bahrami

The next afternoon, after the crew returned to work and the excitement was contained over the new find, Sophie asked Jean-Jacques for an extended interview in the forest, just above where we worked. They moved away from the center of activity to greater quiet, where only the occasional birdsong of the territorial red-throated European robin interrupted their conversation. I squinted up the hill, pricking up my ears to hear anything, but it was impossible. I could see Vincent quietly clicking production stills as Sophie coaxed prehistoric secrets from the grand master.

I remained curious as we retired to the village of Carsac, about twenty-eight miles away. This was where the archaeologists camped and pitched their tents in the large backyard where Harold Dibble, one of the key dig directors, had set up the camp and lab. My old archaeology professor in graduate school, he was the reason I was here. Harold had found a shack of a place in the village, an old tobacco-drying barn, a séchoir à tabac, and turned it into the archaeologists’ home base for his digs throughout the area. While better than pure camping—the dig directors slept under the séchoir’s roof while the crew pitched tents in what was an old farmer’s field—it was still pretty rustic. Crew showers and latrines benefited from the shelter’s hookup with indoor plumbing, but were so “prehistoric” that they had taken to painting Paleolithic designs of hands, bison, and a couple of shagging mammoths on the water closet walls.

The Dordogne had never been industrialized and to this day remains a place where people live close to the land. Once it had been famous for its high-quality tobacco, but today with smoking falling out of fashion, other equally celebrated traditional crops have expanded into old tobacco fields, from corn and sunflowers to walnuts and wheat. It is a region also famous for the native black truffle, a seductive tuber we found at times growing just under the pebbles near oak tree roots at La Ferrassie when we cleared the ground to open a square. Once, we even found a white truffle, near the surface of the back wall where the Neandertal man had been found. (Girolles and porcini also populated the forest, and I often saw the local volunteers using their break time to search for mushrooms for that night’s meal. The forest was also rife with black and yellow salamanders and frogs the size of quarters, and rabbits, fox, wild boar, and red deer. Though nothing like the Paleolithic climate of the past, these rich natural realities made it hard not to think about what smart and clever people Neandertals had been to make this land their home.)

Harold had converted the wooden tobacco barn into a lab where the site sediment could be brought back, processed, catalogued, and analyzed before going into storage. He also renovated a small stone structure that had been added to one side of the barn and made it into his little bungalow, his pied–à-terre in La France so profonde, it included Neandertals. The house and lab sat on the edge of one of two main roads through the village, passing the twelfth-century Romanesque church and leading to the cemetery. His backyard tumbled downhill from the road toward where the Enéa Creek flowed nearby. That creek was a hint as to why this village was so central to prehistory.

The original human inhabitants along the Enéa had been Neandertals. They had most likely been attracted to good water and the limestone caves overhead carved by the tributary of the Dordogne. They had lived in three of four caves a stone’s throw away on a ridge on the other side of the creek. Collectively called Pech de l’Azé, with each cave distinguished with a number, Harold had dug at Pech IV with his mentors, François Bordes and Denise de Sonneville-Bordes. These two were the original Paleolithic archaeologist couple that had put Carsac on the map as an archaeologist’s home base, a tradition Harold has carried on after their passing.

Rather than camping in Harold’s backyard, I was living in the Bordes’ old stone barn. I rented its loft from their daughter, Cécile. It sat across the garden from the main house, where I crossed to greet Cécile each morning and evening, plus her two dogs and three cats, and to use the facilities. It was a five-minute walk to Harold’s dig house, along the same road that passed the church and led to the cemetery. There, François and Denise are buried in a limestone tomb covered by flint tools made by students who left them there as affectionate grave offerings, much as guitarists leave picks at the tombstone of Robert Johnson.

Carsac was so ideal and important in so many ways as an archaeological home base that it was worth the daily fifty-six-mile round-trip drive to La Ferrassie along sinuous country roads that made detours around the region’s infinite limestone outcroppings and forests. Those limestone formations and those forests were the reason why this was one of Europe’s most concentrated areas for prehistoric human habitations, as well as a popular holiday destination for today’s hominids hell-bent on the same things: good shelter, great food, and beautiful landscapes and climate. As the region’s tourist office liked to advertise, the Dordogne has been ‘a vacation destination for 400,000 years.’ The good life has deep roots here. Just ask Homo erectus, our earlier ancestor who is related to both Neandertals and us, as he ventured into Europe.

An international team drawn from diverse places such as Australia, Iran, Canada, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Belgium, Holland, the USA, Greece, France, and England, the crew prepared the daily dinners that reflected their homelands’ culinary inspirations. Harold also directed the menu plans and had his arsenal of tried and true recipes that made nearly everyone happy. These were French and American-style dishes he’d mastered and refined over decades of dig work. As the crew prepared dinner for thirty-five downhill in the backyard on outdoor gas burners and on an open fire, uphill, inside Harold’s little stone house, the dig directors present that day gathered to decompress, review the day, and plan for the next one.

The team’s directors were six scientists: Paleolithic archaeologists Harold Dibble from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Alain Turq from the Musée National de Préhistoire in Les Eyzies, Shannon McPherron from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Dennis Sandgathe from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, and geoarchaeologists Paul Goldberg (aka the master soil sommelier) from Boston University and Vera Aldeias also from the Max Planck in Leipzig. They also enjoyed input, collaboration, and visits from other respected scientists, such Jean-Jacques Hublin (Max Planck), Paul Mellars (Cambridge), Wil Roebroeks (Leiden University), and Gilliane Monnier (University of Minnesota), among many others.

Virginie Sinet-Mathiot, a bright rising star in paleoanthropology from Bordeaux, headed the lab. Her remarkable skills and unflappable cool kept it in remarkable order each day as it received numerous buckets of sediment from that day’s work at La Ferrassie. These had to be carefully processed, catalogued, and stored in the next twenty-four hours to be ready for the next daily delivery, where it all began again. While she was often at the lab and so deprived of visiting La Ferrassie where everyone felt the excitement was, Virginie knew something that few outside of this work know: most of the biggest discoveries in archaeology, especially Paleolithic archaeology, are made in the lab, not in the field. Excavators are too burdened with digging and documenting most of the time to realize what they are finding, especially when it is a small piece of bone or flint or a soil sample that needs a microscope and long hours of analysis. That just-discovered molar was an exception.

Thanks to a software program Harold and Shannon wrote, all artifacts at the dig were each shot in with a laser that then fed into the program and noted the exact location of that item into a three-dimensional map of the site. When something was found in the lab, the original location and context could be pulled up through this program. The program also allowed a person to view the site in three dimensions and to begin to see patterns of where more flint or broken animal bones lay or what the spatial relationship of fire hearths were to each other, and the like.

Today five of the six core directors gathered upstairs along with our special visitor, Jean-Jacques Hublin. I looked in on what was for dinner downstairs—roast pork, sautéed red cabbage, a salad of greens, carrots, tomatoes, and cucumbers, and garlicky green beans—and then went up the hill and straight to Harold’s cottage living room. In between, I received exuberant greetings and hand-lickings from Gary, the neighbor’s black Labrador, who had decided to live with us and escape his life with three Shar-Pei. In his own way, he contributed to the work of the camp by chasing down and devouring the apples that fell into the yard from the two apple trees.

I myself was a sort of upstairs-downstairs person in the crew. My role as journalist and anthropologist had afforded me precious equal access to both worlds. And permission to drink, within reason, Harold’s scotch. I stepped inside his bungalow as he was pouring himself a scotch and soda on ice. I sidled up shamelessly and poured mine neat. Outside of the scintillation of touching Neandertal dirt, this was my favorite time of day.

Harold sat in his leather chair and swirled his drink before taking that first rewarding sip. The sound of good ferment tumbling through ice was as seductive as that tiny European robin in the forest, pleasingly punctuating the cadence of rich conversation.

Jean-Jacques was already seated with an aperitif of white wine set before him on the coffee table. I took my glass and sat next to him.

“What, may I ask, did you and Sophie talk about in the forest?”

He flashed his engaging smile. “I told her that we are all storytellers, and that we are drawn to origin stories. Of course, it is totally contradictory to the concept of evolution, because there is no ‘first’ anything. But people want the first stories. They want some sort of an Edenic moment. Somehow, it reconciles with the Biblical perspective, with all these theories about the African Eve and the Garden of Eden. We want a first something. And then it’s also related to the notion of humans being different from the animal world and somehow being separated by a trench. So, you have to be on one side of the trench or the other. I told her that this is the problem with Neandertals.” He took a sip of wine. “Neandertals for a long time were on the other side of the trench. So we emphasized the differences. But now, somehow, they’ve passed over to this side of the trench. Now, we are erasing all differences because we want all humans to be the same.”

“How did she respond to your answer?” I asked, loving how in a few breaths he’d summed up the root of most motivation, passion, and contention in the field. I had met Sophie through other prehistory circles two years prior to becoming a crewmember at La Ferrassie, and knew that her humanistic views of life included the Neandertals. Only the day before she’d had another brief chance to interview Jean-Jacques and had asked him about Neandertal and Cro-Magnon intermingling; the dreamy idea of romance and wooing, a rainbow coalition, seemed to be implied in the tone of her voice. He had disabused her of the idea. He explained that there probably weren’t any ‘flower bouquets and candlelight dinners,’ that we really have no idea what these interbreeding encounters looked like, and that romance was less likely on the menu than fast food. I thought I could see the air seep out of her sails and felt the sting myself, for I too was a part of the rainbow coalition.

I confess I also carry a flame for the Neandertals. I even like to think my percentage of DNA from Neandertals in modern humans, that estimated average of 1.5–2.1 percent among people of Eurasian ancestry, is the full 2.1 percent. I even round it up to 3 percent. I liked them because to an introvert in a society that encourages extroverts, they seemed to be similar, living in smaller groups and possibly not needing to talk as much. We Homo sapiens are gabbing all the time, chasing away dinner without knowing it. I also noticed the same tendency among the local volunteers. One, Didier, even wore a T-shirt, black with white lettering, that simply said “4 percent de Neandertal.” (That was the top end of the percentage range when the genetic studies first came out, before they were later adjusted.) He and his fellow trench mate, Fabien, had confessed earlier their disenchantment with modern life as a big part of their draw toward prehistory; the world since the advent of agriculture some 10,000 years ago has been nothing but a hominid-made mess. As Vera succinctly said as we drove one morning to La Ferrassie, “Farming changed everything.”

Three percent or not, at the same time I know that I have to keep my wishful emotions separate from the actual science and let the evidence speak (Harold’s favorite mantra) about what was and was not possible. I also secretly suspected that everyone had their own dance with objective and subjective reality, and that those who were willing to admit it, the really honest ones, were best prepared not to mess up the actual data, or ignore the lack thereof. People jumped to conclusions with too little information and Jean-Jacques was right, it was rooted in our storytelling brain that desired origin stories.

Like Jean-Jacques, Harold was also deeply aware of and affected by this subjectivity in the field. When he called others on it, he was often criticized for not liking the Neandertals or for denying them their humanity, which was never his point. In fact, I’d found Harold far more sympathetic toward Neandertals than us Homo sapiens, a reality that would surprise many of his critics. Only two weeks earlier, at another “Scotch Time,” as Harold affectionately calls these early evening sessions, he leaned passionately into this theme when someone brought up the idea that we moderns are inclined to like Neandertals because they were similar to us, because they were, in Jean-Jacques’s language, on our side of the trench.

“Let’s go with the evidence,” Harold warmed into the topic with his familiar mantra, swirling the ice in his glass and rolling his eyes. “If the evidence shows Neandertals were like us, I’m all for it. But if the evidence does not show it, don’t give me ‘I like Neandertals.’ Who cares if you like Neandertals? The question is, do we have the evidence to say that they’re like us or not? Oh, and the other argument I just love is, ‘Oh, we don’t want to be mean to Neandertals, they’re like brothers to us. Oh, Neandertals, you’re just like us.’ Meanwhile, Neandertals lived over 250,000 years. We’ve been around for maybe 160,000 years and I think we’re going to extinction really fast. They didn’t do that. So, what are you going to tell a Neandertal when you meet him on the street? Are you going to say, ‘Hey, aren’t you happy to be just like one of us?’ He’s going to look you in the eyes and say, ‘Fuck you. I don’t want to be like you.’ Why do you think it’s a compliment to make them like us? We’re not so great. I think it’s pretty bad that the only compliment you can give a fossil ancestor is to be just like us.”

“She was kind of amazed.” Jean-Jacques brought me back to the present Scotch Time. “And she said, ‘I didn’t know scientists were interested in this kind of thing.’ I said, ‘Yes, I think the problem is that scientists do science and they think scientists of the nineteenth century were totally biased by their preconceptions about this and that, but it is in fact exactly the same today.’ We project our fantasies about our values, nature, ecology, economy, family, and so forth, onto what we study.”

Harold listened, smiling appreciatively and taking another sip of his drink. He was fully relaxed; he wouldn’t have to use his mantra, at least not today.

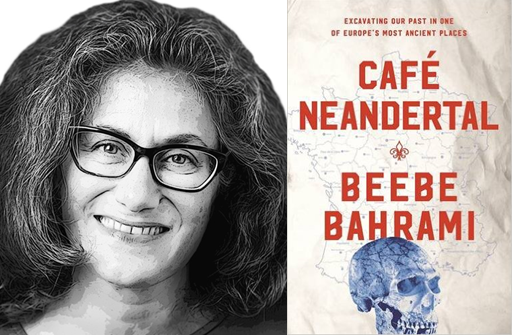

Beebe Bahrami is a professional writer known for award-winning travel, memoir, archaeology, outdoors and adventure, food and wine, spiritual, and cross-cultural writing. Author of The Spiritual Traveler Spain (Paulist Press, 2009) and Historic Walking Guides Madrid (DestinWorld Publishing, 2009), her work also appears in Archaeology, Wine Enthusiast, Bark, The Pennsylvania Gazette, National Geographic books, Michelin Green Guides, Expedition, and Perceptive Travel, among others. She wrote two travel apps, The Esoteric Camino France & Spainand Madrid Walks, and maintains two blogs, Café Oc, on life in the Dordogne, and The Pilgrim’s Way Café, dedicated to exploring the world on foot. You can read more about her and her writing at beebebahrami.weebly.com.

This excerpt from Café Neandertal is published by permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2017 Beebe Bahrami.

Photo: Beebe Bahrami, Steve Mullen

Published on March 1, 2017.