The phone rang in the middle of a noisy Sunday family dinner in the kitchen of my London home, one evening in February 2002. I had just finished serving the second course. My husband and three children were loudly debating several issues at once and laughing as they argued. My daughter and my middle son were in their teens, my oldest son in his early twenties. I was forty-seven.

I closed the door to the kitchen and went to pick up the phone in the dining room.

‘Is this Lena?’ said a very Russian-sounding man, in English. ‘Yes. Who is this?’

‘I am calling from Moscow. Are you in good health? I have to tell you something very upsetting. Please, sit down.’

‘I’m OK. What is it? Please, speak Russian if you prefer.’

He did. His voice trembled with emotion. Most Russian voices do; this did not surprise me.

‘Does the name Schneider mean anything to you?’ ‘No.’

‘Really?’ He seemed genuinely shocked.

‘Schneider was the name of your real father. Your mother was with another partner before your father. His name is Joseph. You are his daughter. She knew him as Schneider but his real family name was Minster. They were Americans living in Moscow. Your grandfather was once an undercover agent for the Soviet Union. He—’

The man on the phone suddenly lost his confidence. He was stumbling from one topic to another as he tried to tell me so much, very quickly. The strange thing was that I believed him. Without understanding why or how or even what was actually happening to me, I felt the truth of this story. Something clicked, fell into place.

‘It took me so many years to find you, Lena. So many years.’ He was my uncle by marriage, the ex-husband of Joseph’s sister. The reason why he had undertaken this search was that he had an only daughter who was a little younger than me, and who was living in the States. He wanted his daughter to know her family. He felt that this was very important.

‘Your real father is living in New York. The entire family emigrated from the Soviet Union in 1973, as Jews. You have a half-brother by your father’s second wife… Also in New York.’

I felt the first pang of disappointment, and pain. Why wasn’t this father looking for me? And why had my parents never told me?

The man on the phone (who finally introduced himself as V) said I should speak to my parents to verify his story. And did he have my permission to give Joseph my number? I agreed to both, and we hung up.

I didn’t go straight back to the kitchen. I phoned my mother in Hamburg and told her about the phone call. She was silent. Silence–in conversation–is practically non-existent in our family. My parents are always talking, in expressive cadences, about everything under the sun. Except their secrets, apparently.

So I knew she was confirming the truth when she didn’t say anything at all, and then: ‘Let me speak to your father. I’ll call you right back.’

The phone rang again. ‘Lena? Eto tvoy otec govorit.’

A man with a much stronger voice than V’s, speaking in Russian with a slight stutter. ‘Lena? This is your father speaking.’

We had a surprisingly normal conversation, about where we both lived, what we do… As if I didn’t already have a father. In middle age, I was suddenly transported back into my infancy. What did I know? What did I not know?

A year earlier I had published my first novel, called The Nose. It was the story of a young American woman living in London, whose parents, especially her mother, had created an impenetrable wall of silence between themselves and their children. Only as an adult does my heroine almost accidentally stumble into uncovering and understanding the truth about her family. I thought I had invented and imagined it all. But perhaps I was writing about what I did not yet understand, but had lived with all my life.

Before we said goodbye I told Joseph that I was flying to New York in a week’s time, on a journalism assignment. We arranged to meet. He sounded very excited.

Then I called my brother Maxim in Berlin. My father was visiting him, and while Maxim and I spoke I could hear his voice in the background, talking to my mother on his mobile. I quickly told Maxim what had just happened.

‘Why are you so lucky?’ he said, laughing. But then he was serious: ‘Are you OK?’

‘I am,’ I said. ‘Or maybe not. I don’t know.’

My parents then both called, in quick succession. Each confirmed the truth of V’s story.

‘To be honest,’ said my mother, ‘I am relieved it’s out.’

‘I’m worried that I am going to lose you,’ said my father.

No one except my brother seemed to be concerned about how this bombshell was affecting me. My parents were the core, I was the periphery. Whose story was this, really? And what was the story?

I rejoined my own family in the kitchen, and gave no sign of what had just occurred, how my life–and in some way theirs–had just been turned on its head. I knew this: my father would always be my father, whoever Joseph might become to me.

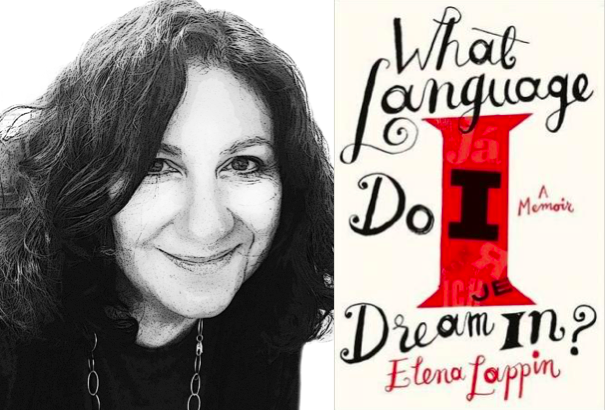

Elena Lappin is a writer and editor. Born in Moscow, she grew up in Prague and Hamburg, and has lived in Israel, Canada, the United States and—longer than anywhere else—in London. She is the author of Foreign Brides and The Nose, and has contributed to numerous publications, including Granta, Prospect, the Guardian, and The New York Times Book Review. She is the editor of ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press.

This excerpt from What Language Do I Dream In? is published by permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2016 Elena Lappin.

Photo: Elena Lappin, private

Published on February 1, 2017.