In 1970, the satirical magazine Hara Kiri shut down under pressure from French political elites after an issue that parodied national mourning over General de Gaulle’s death. A long series of scandals culminating in censorship met a coup de grace when Minister of Interior Raymond Marcellin threatened the magazine, calling it ”dangerous for the youth” and ”pornography” “Gaulliste”-era France was a time of official prudery.[1] Hara Kiri was pulled, to be reborn later on as “Charlie Hebdo.”

After a name-change and forty more years down the road, few would have imagined such a red carpet of A-list mourners and detractors unrolling after the 2015 massacre by the Kouachi brothers. The killers acted in coordination with an attack on a Parisian kosher supermarket, “Hyper Cacher.” Among those killed was Yoav Hattab, son of Tunisia’s most influential rabbi. Like many young Tunisians, Hattab was studying in France after having recently voted in Tunisia’s first democratic elections.

The November 13, 2015 attack summoned unlikely mourners from the political elite. A towering human mausoleum rose above the French ground-zero, propped with flags of causes that were alien and alienating to the leftist ideology of the Hebdo family, whose hard-earned infamy had preceded them for decades, only to be trivialized into consensus and tricolor shrouds. Once murdered in the crossfire, the staff could no longer ward off the acclaim they dodged in life from those statesmen who were strident accelerators of the various “wars on terror.” Being dead also rendered them unable to defend themselves against accusations of racism, being leveled from a different pulpit, mainly that of left-liberal consciences from across the Anglo-sphere. Prestigious writers, literary agents, and academics based in the US and UK signed a letter published on The Intercept (a groundbreaking platform by American journalist and whistle-blower Glenn Greenwald) in stark condemnation of PEN America for the posthumous Charles C Goodale award for Charlie Hebdo. The letter, speaking in the namesake of the dignity of embattled Muslim and “Maghreb” minorities in France, vied to take up the banner of the under-represented of France’s former colonies. Colonialism, all too easily forgotten, was invoked to explain the rampages of French jihadists. The letter implies how a “dominant narrative” in the guise of free-speech and cartoonists had stifled other “hidden narratives” of those ex-colonized presumed “voiceless—” the French Arabs, Muslims, and French Africans.

A strange deficit persisted among the accumulating signatures—there were about two-hundred in Intercept—beneath a letter invoking French colonialism, commisserating the ”unrepresented” and ”marginalized voiceless’’ of French minorities and the formerly colonized, who ought not be mocked by cartoonists. With a fraction of exceptions, very few of those signing were Francophone. Did “the voiceless” here also refer to writers without Anglo-American (academic) credentials?

In her correspondence with PEN America, Deborah Eisenberg (winner of the Bernard Malamud award) compared the French cartoonists to no less than Julius Streicher, cartoonist of Hitler’s and Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry. Whether or not Eisenberg knew it at the time, those victims include surviving cartoonist Zineb El-Razhaoui, deceased Algerian-born copy-editor Mustapha Ourrad, and deceased Tunisian psychiatrist Elsa Cayat. Chief-Editor Charbonniere’s widow left to mourn Jeanette Bougrab. Her father was one of the ”Harki\”Arab conscripts who fought for the French during the 1950s Algerian wars: hardly the image of “white privilege.”

What did “Maghrebians” involved in literature, philosophy, or art think of the Hebdo affair, and of the repudiation and shaming of Hebdo in the Anglo-sphere?

A counterpart to The Intercept letter was published in a French language left-wing magazine: Mediápart, which in France has a similar function to The Intercept’s whistle-blowing and exposing of security-mongering authorities.

Hundreds of signatures, by mostly Arab and Francophone writers, scholars, and actresses from Muslim societies backed a Declaration du Solidarité avec Charlie Hebdo published online.[2] The Mediápart petition shows a different message of compassion with those murdered, signed mostly by Arab-Muslims and Arab-Jews—those who are usually the first, foremost victims of jihadist punishments of “the blasphemous.”

Two letters on free speech that never met, distanced by sea and by language, from riveted secularity. Because of non-translation, the signatories operate as if in parallel worlds, whose alienated inhabitants are mutually unaware, speaking past one another: a world where all encounter is avoided, perhaps intercepted, or simply divided by a wound. Francophonie’s more complex reactions to November 13, 2015 were overlooked in the crossfire between reactionaries.

Here, for the first time in English translation, are words from some of these Francophone-Muslim and African statements regarding the attacks by jihadists who took offense.

Kamel Daoud is the Algerian novelist who has evaded a sentence condemning him to public execution by jihadists ever since the publication of his French-language novel Meursault: Contre-enquête (The Meursault Investigation), telling a story of Algeria from the point of view of the brother of the Arab who was murdered by the famous Mersault, the cold-headed notary from Albert Camus’ The Stranger. Daoud, who admires Camus, claims he has not written the typically revisionist post-colonial novel that gives an obscured or silent native character their speaking-turn, initially overlooked by the European narrator.

In retaliation came threats of death and execution from Algerian jihadist activists, putting him in a vulnerable situation close to the plight of Hebdo’s fallen. Asked for his opinion, what resulted edged on a poem: “Two days of silence. Words rush through the mind. Drawing kills, thinking kills, writing kills, being free kills, being upright kills, to play kills, to dance kills, to laugh kills, denunciation kills, loving kills. Two days to ponder solely about death, their deaths and the others’ deaths, deaths of the illustrators of Charlie Hebdo, of the two Tunisian journalists who were executed, of deaths elsewhere (…) It is a match between those whose motto is “I am free” against those who scream ” I am Allah.”

Daoud, in a later interview had a more critical regard of mass-invocations of “Charlie:” “I find myself alienated by the attempts to make Je Suis Charlie into some kind of religion, and into an inquisition. I support the cartoonist against the killer, but I would not want that solidarity to be made into a mobile tribunal for judging who is truly Charlie and who isn’t.”[3]

Perhaps one of the most moving reactions was from Gilbert Naccache, spokesperson of Tunisia’s Communist party. The Jewish atheist intellectual enjoys popularity, especially with young people who participated in Tunisia’s revolts that began in 2010. Naccache was imprisoned from 1968 until 1979 under the secular regime of Habib Bourghuiba, which like the successive regime of Zineh Dine Benali, persecuted both the Muslim Brotherhood and Marxist dissidents. In 1968, young Tunisian students echoed and resonated with the uprisings in France. Michel Foucault had resided in Tunisia, professing to Arab students. Even in dissent, Tunisia remains keen on French cultural and intellectual developments. France has remained oblivious to its former colony as if it were little more than a far-removed banlieu. In prison, Naccache wrote the poetry collection “Crystal” (published after his release).

In one of his articles, Naccache’s reacted to the kidnapping of two Tunisian journalists by jihadists in neighboring Libya, in the light of the Paris rampages: “The episodes of Islamist movements in the Arab world serve to illustrate just how obstinate the sorcerers’ apprentices continue to make the same errors. The worst manifestation to unfold so far before our eyes, goes by the name of Da’esh (ISIL) and from its origin was being financed in order to facilitate the destabilization of Middle Eastern states, so as to make the remaining work of large corporations easier. Once again, Frankenstein is surpassed by his creations. (…) That anti-civilization finds its refuge behind a religious phraseology that serves to exalt nothing more and nothing less than the death of Humankind and of enlightenment tradition.

The scope of the chasms engendered by the inequalities between nations and at the hearts of nations is to be seen in how that anti-civilization functions: as a mirror, that is entrapping an unfortunately large amount of young people for whom ”civilization” no longer seems capable of yielding any positive ideals.

The actors behind the attack on Charlie Hebdo, and their Libyan co-culprits who may have executed two Tunisian journalists Sofien and Nedhir whom they abducted (…) were devised to punish those people who dared to speak out.”

Among those taken captive are journalists, cartoonists, women, and men whose work is that of mobilizing and expressing a sense of purpose or thought. These aggressions do not only target the freedom of the press or the freedom of information in their crosshairs; rather, they also target thought and the very capacity to think.

“Outraged at having noticed the counterfeit artificiality of those lofty values in the shop-window showcase of the dominant so-called ‘civilization,’ these youths who like Narcissus hover upon the black mirror of total revolt, lose themselves in the deathly reality of that mirror. But no bullet will ever succeed in arresting thought. Today we can mourn for our friends, the journalists and the others whose only misstep was to encounter the messengers of death. Underneath the emotion produced by these events, what stays with us is the certainty that human thought, far from perishing or from surrendering to blows, will always come out stronger and conquering. It is possible to murder a person who thinks, but to murder one is to create a hundred, a thousand others.”

“Your bullets, your rockets, your tanks, even your bombs, can never destroy thinking itself.”[4]

Felwine Sarr, Senegalese essayist, and author of Méditations Africaines (African Meditations) explained in an interview the ambivalent African responses following the Parisian tragedy: “Globally, it is largely the compassionate response that has taken precedence. In Mali, that expression of compassion doesn’t cease to be as genuine and strong, because this country has in its flesh lived through the same experience of jihadi terrorism. Geopolitics has disappeared momentarily to make way for simple human sentiment. The more ambivalent sentiment probably has to do with the fact that, seen from Africa, Europe once more gives the impression to be rather fixated on herself. When such a tragedy befalls her, she demands of the world its expression of a compassion that she does not seem capable of feeling when the same tragedy befalls others who are stricken by the same crises. I believe the way to interpret these ambivalent reactions is by reading in them a desire for reciprocity, for recognition of our common human-ness.”[5]

Lebanese writer Hoda Barakat, a signatory of the letter of solidarity with Hebdo, answered Le Monde’s request for an Arab response with her piece “The Shame and Rejection,” explaining how the gunmen were not only the sons of jihadi fundamentalist nihilism, but were also the orphans of the Republic’s broken promises to expatriate immigrant laborers from former colonies who are often consigned to the austere enclosures of banlieu. From an interview in Il Manifesto, translated in English in Raya Agency for Arabic Literature: “We have entered a new era of human history, dominated by terror, but we are unable to understand it fully because we have outdated tools, overtaken by events. We do not understand Isis’ nihilism, and especially we do not understand entirely how this appeal to terror and death can conquer a part of the new generations, to proselytize in countries that have long known war, but also in Europe”[6] (…)

“When Le Monde asked me to write I was not optimistic, because I could already see what would follow the first moments of collective mobilization, as in fact happened. After the anger and fear, we immediately stopped asking why young people born and brought up in France can be pushed to identify with an ideology of suicide and death. In many ways they are the ‘orphans of the République,’ one of the most terrible and tragic consequences of the fact that the democratic France has never taken up at the bottom of its colonial and imperial past.”

Lebanese novelist Aamin Maalouf wrote a poem in solidarity with the victims, l’Automne de Paris, immediately adapted to music by his nephew Ibrahim Maalouf, who performed it on the radio. [7] Maalouf’s indictment compared the Kouachis to Anders Breivik, the Norwegian businessman-turned-gunman, whose killing spree in 2011 murdered seventy-seven mostly immigrant-origin youths who partook in a leftist party’s summer camp.[8] Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury and Algerian Yasmina Khaadra (who spoke at length to Al Jazeera about his motivations) also signed the Mediapart declaration, as did Dutch-Moroccan Goncourt-awarded writer Fouad Laroui, who marched with the first demonstrations of solidarity, but who also insisted on the need to understand why the youths of the Parisian ghettoes feel that Enlightenment values had not applied to them.

Maryam Satrapi, Iranian exile and author of the graphic novel Persepolis, admonished a well-meaning younger generation of cartoonists in the United States not to let the logic of fear win, while questioning the timing of the conversation about Hebdo’s “offensiveness” just after the killings.[9] Censorship has followed Satrapi far from the Iran she left as a teenager. When the film version of Persepolis was censored from Turkish state television, she resorted to the Tunisian lawyer Chokri Belaid to defend her. They won.

Belaid’s more important career, that of a pivotal spokesperson for Tunisia’s communist party and in class struggle politics, led to a gunshot to the head from a Salafi assassin in Tunis in 2013, when the Left’s popularity threatened to break the Muslim stranglehold among impoverished laborers of the Southern provinces.

The expression “lost in translation” applies to many comedies of error. Perhaps it is precisely the absence of translation, and the selectivity of that very absence (neglect, suppression, at times censorship) that of itself becomes a device far more dangerous and effective than visible, published propaganda. Petitions by French-Arabs did not enter the conversation with those across the English Channel or the Atlantic.

Puzzled by their experience of one another during the controversies about Hebdo raging amid Anglo-American and French progressive intellectual communities, it were as if France and its French-speaking former colonized had been reduced the very vision of the Orient that Said had warned of. The extension of solidarity and of recognition never took place—as if those of France’s formerly colonized peoples were mostly like the Kouachi’s themselves, deprived and formless ones sans erudition, needing a “voice” in the face of all the authorities who tout enlightenment values like a bludgeoning tool of the colonizer against the ‘’voiceless’’

But the vote of compassion of intellectuals on one side of the Atlantic and of the wartime front-lines has no reason to stop there, in pious silencing, without extending towards an engagement, a dialogue in letters with the intellectuals of the former-colonized, the Francophone. It was a gesture of politics suspended—in that conventional logic of the post-political era, chanting “people of above politics,” “enough ideology already, these are people we’re talking about!” Thus, the notions of intellectual freedom, freedoms of press, and freedom to think must be suspended, trivialized as mere pastimes of the privileged, embarrassed pale in the face of true suffering. That post-political logic is also a violence against those who suffer, against those who were already oppressed by the forces that took hold of the formerly colonized societies, supposes that no voice from suffering can also think, can also know of rationality, or of beauty, freedom, or erudition. The final violence against those who are suffering is to suspend or doubt their ability to think or speak, as if it were a favor, or a legal plea of insanity to elude the violence of the Western courts and of judges.

These were unfortunate reactions coming from those in the most erudite heights of the Anglo-phone world who had the false impression that Hebdo was simply a right-wing propaganda front, demonizing Muslims at the service of Sarkozy’s preferred rhetoric. Why did left-wing solidarity from the Anglo countries not extend to the many writers, scholars, and artists from French ex-colonies, weary of jihadist violence directed mostly towards them? Is the left unable to think of the oppressed as having a living culture to defend above the mere devastated condition of being oppressed?

Albert Camus, who never lived to see our beast of a century, insisted “the duty of the intellectual is not to be on the side of the executioners.” Such an indictment is by no means obvious, yet today goes unheeded by intellectuals who repeatedly side with executioners (Obama’s drone-program; the offended jihadists; Assad’s violence) regardless of the political or economic position they ascribe to. Selective compassion, or an ethical rationale, a moral logic trying to substitute the force of intuitive compassion in times of deceptive image-making, may have been sincerely at the root of many of the signers of the objection-letter to PEN America. Perhaps among others it was the resentment spoken of by the Senegalese author: an objection towards the Euro-centrism of mourning only for Parisians—not for the victims of Boko Haram, not for victims of European military excursions and weapons-sales to the East, and not for the painters, artists and cartoonists in Asia and Africa who continuously brave jihadi belligerence.

Letters were sent, and different intellectual communities with much to learn from one another were mysteriously kept from engagement, perhaps due to the absence of translation. No conspiracy lies and the root of the Western ommission of Francophone responses to November 13,2015. To give solidarity, like listening to the dead, is an art, demanded of us, those living.

Writer and visual artist Arturo Desimone was the first Arubian to be born as an Argentine citizen on the island Aruba, where he lived until the age of 22, the year of his emigration to the Netherlands. He is currently based between the Netherlands and Argentina, while working on a long fiction project about childhood, diasporas, islands, and religion. Desimone’s articles, poetry and short fiction pieces previously appeared in The Missing Slate, The Drunken Boat, Círculo de Poesía (Spanish) Acentos Review, Open Democracy, and in the Netherlands-based art criticism magazines Mister Motley and Al-Arte mag. Tattoo Moon, a play he wrote won a prize for young immigrant authors in Amsterdam in 2011, and was serially published in Rosetta, an international literary journal published by the of University of Istanbul.

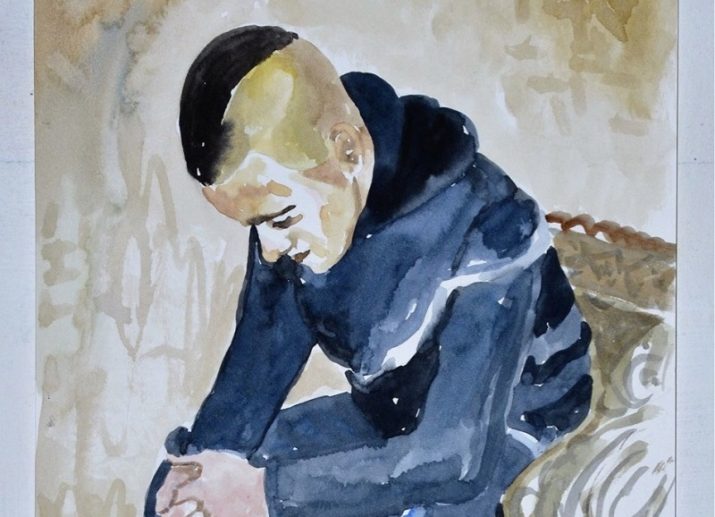

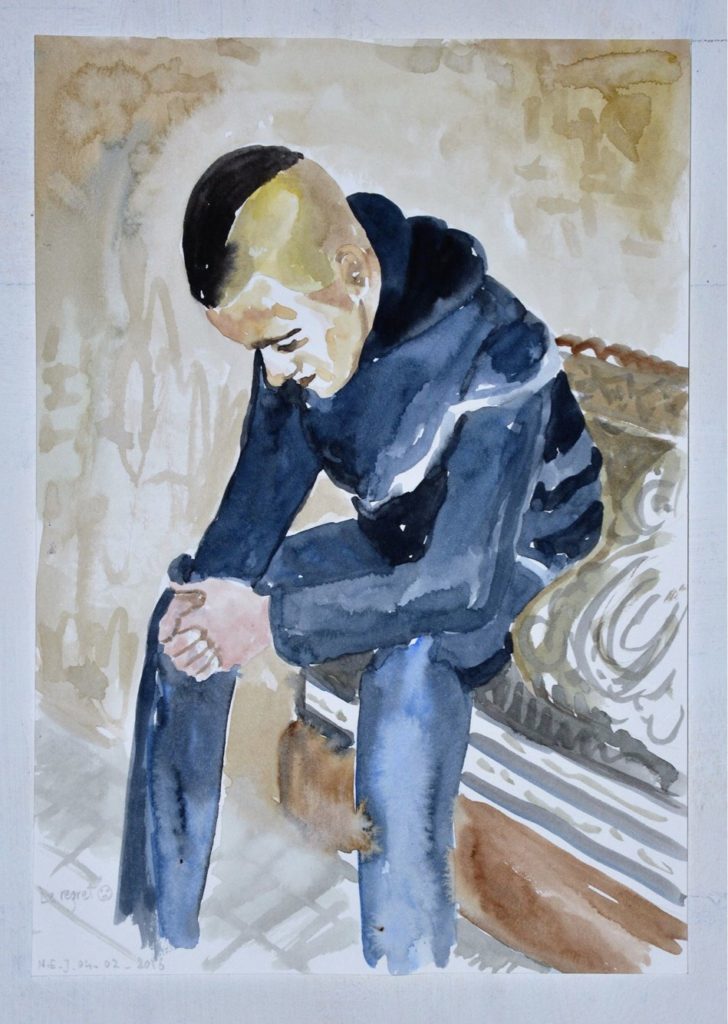

Photo: Nour Eddine Jarram’s painting ”Le Regret”

References:

[1] “C’est quoi l’esprit « Charlie Hebdo » ?” Jaxel-Truer, Pierre Ed. Le Monde August 1, 2015 Web.

[2] “Déclaration Du Solidarité Avec Charlie Hebdo.”Mediapart.fr. Ed. Club De Mediápart. Mediapart, 13 Jan. 2015. Web.

[3] Daoud, Kamel. “A Nouse de Décider Quel Monde Nous Voulons .”Le Courier Internationale. N.p., 09 Jan. 2015. Web.

[4] Naccache, Gilbert. “C’est la pensée qu’ils veulent tuer.”Facebook blog of author. N.p., 10 Jan. 2015. Web.

[5] Cessou, Sabine. “Attentats à Paris.”Radio France International. RFI, 2015. Web.

[6] Caldion, Guido. “Exile has little to do with geography.”RAYA. Arabic Literature Agency, 20 Nov. 2015. Web.

[7] Hacen, Aymen. “Charlie Hebdo.”Causeur. N.p., 10 Jan. 2015. Web.

[8] Valenta, Marka. “Breivik: Killing the Left.”OpenDemocracy. OpenSociety, 11 Aug. 2011. Web.

Published on February 1, 2017.