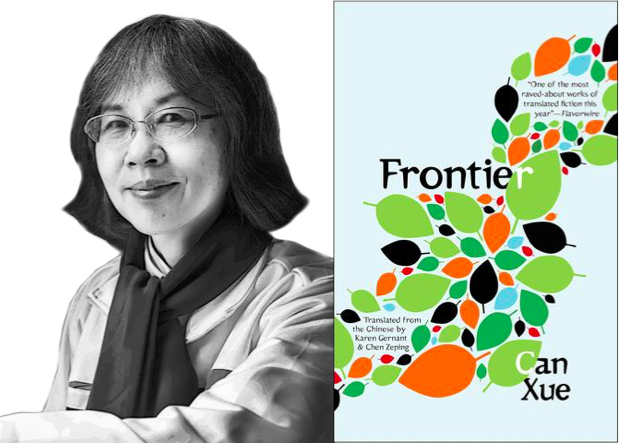

Translated from the Chinese by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping

The wooden boxes were arranged in a long line next to the jet-black river. Little Leaf ’s box was the largest one. You could tell from the dark color that these boxes were quite old. They stuck roses into each corner of the box.

The roses were weird: even though they’d been out in the sun day after day, they still looked fresh, as if rooted in the ground. Early in the morning, someone shouted from the riverbank: “Little Leaf! Lit—tle—Leaf…”

Little Leaf and Marco climbed drowsily out of the wooden box. When they were wide awake and looked across the river, they saw no one. Marco said it had to be the person from Holland, who had come to urge him to return to that country. Because he knew Marco wouldn’t listen to him, he had shouted for Little Leaf, instead.

Nights on the riverbank were terrifying: it was as if the violent wind would blow the boxes into the river at any moment. Mixed with this strong wind were many howling wolves. The two of them were accustomed to this environment. Sometimes Marco lit a candle. Watching the flickering light, he told Little Leaf stories of Holland. “Mama, ah…” he often lamented. Little Leaf wasn’t nearly as calm as Marco. She trembled when the wolves howled. When Marco told his stories, she couldn’t see his eyes. This upset her. Although Marco’s eyes were open, his pupils were invisible in the candlelight. During the day, they worked in a large restaurant on the river-bank. Those who dined there were mostly also migrant workers from the countryside. Some of them also lived in the boxes on the river-bank. Little Leaf was a waitress, while Marco did odd jobs. The work was tiring, but at the restaurant they saw some people and things that aroused their interest. A stolid old man showed up every day for his meals. After examining him closely, Little Leaf concluded that he was more than seventy years old. But his clear eyes looked very young. He didn’t eat much—a small bowl of noodles was enough. And sometimes he ate nothing, asking only for a glass of water. At such times he apologized to Little Leaf, “I’m too old. My body can’t handle too much food.”

Marco told Little Leaf that this man didn’t live on the riverbank; he lived next to the main road leading to the snow mountain. He had built a temporary wooden house in the white birch forest there. Marco had stayed overnight in that house once. Marco also said the old man had been a temporary worker in a lumberyard. “Where’s he from? It seems I’ve seen him before.” As Marco said this, he looked quite distressed. Little Leaf suspected that the old man was some- how entangled with Marco’s past.

Another regular customer was an old woman dressed all in black—even wearing a black headscarf. When she sat down at a table, she made almost no sound. Every time, she ordered a bowl of soup and a small bowl of rice. She ate unobtrusively. After finishing, she lingered a while, absorbed in her thoughts. One time, when Little Leaf was clearing the next table, the woman suddenly spoke up, “There ought to be a clock here.” She blocked the light with one hand.

“Oh, I’ll tell the manager. But maybe it’s intentional? Nowadays, people all wear watches. Hey, that’s exactly right. Everyone…” Little Leaf broke off, realizing she was babbling.

The old woman forced an ear-piercing laugh, and then stopped laughing and stood up and looked at the picture on the wall—a framed, crude oil painting. Little Leaf had never been sure what the picture depicted: it could be a sail, or it could be a butterfly. She leaned close to the old woman and looked at the painting with her. The old woman said softly, “It’s the clock, all right.”

From then on, Little Leaf kept noticing this woman, and she also started paying attention to this painting. In the past this painting had been inconspicuous, but now it was disturbing. Furthermore, every time she passed it, she heard a tick-tock sound. It did indeed sound much like a clock. On the wall about four or five meters away from this painting was another picture—a mediocre painting copied from a photograph of a sandthorn that looked as if it were sick and dying. These were the only two pictures in the entire dining room. When Little Leaf walked past the sandthorn, she could hear nothing, and didn’t sense anything disturbing. Yet she couldn’t pass by without glancing at it a few times. Why? The tables beneath the oil painting belonged to the old woman. She always sat at one of two tables. One time, she revealed her wristwatch—a large and heavy navigation watch. It looked more like handcuffs. Little Leaf was surprised that she wore a watch and yet complained that there was no clock in the dining room! She wanted to ask her if she worked on a tramp steamer, but she was too timid. The woman herself brought up this subject later. She said that she had worked on a tramp steamer. After she retired and came to Pebble Town, she had hallucinated: she had thought the “she” who had worked on the steamer had died of cancer. And so she wore mourning garments and moved to an old house on the riverside. She spoke somewhat impulsively and grabbed Little Leaf ’s hand, letting go of it only when she finished telling her story. That day, the clock tick-tocked particularly distinctly—and the sandthorn in the oil painting turned colorful and full of vitality.

The old man and the old woman didn’t seem to have anything to do with each other, but for some reason Marco kept insisting they were friends. When Little Leaf asked why he thought so, he said he had seen them together in a coffee shop in Holland. “They weren’t so old then.”

One time, dogs caused a disturbance in the restaurant. A skinny man burst in with a pack of dogs. He ordered food and drink and sat there eating. The vicious-looking animals roamed back and forth in the dining hall. One by one, the angry diners slipped out quietly, and the waitresses took cover behind the door. Then the dogs jumped onto the tables and made a big meal out of the food left by the customers. They also broke a lot of dishes, making a huge mess. Marco and Little Leaf were very excited that day: they had seen these dogs before and thought of them as old friends. The two of them walked back and forth in the dining hall, their hearts filled with indescribable longing.

All of a sudden, a large wolf-dog pounced on Marco, knocking him to the ground. Actually, he fell of his own accord—and quite readily, too. Marco was holding the dog’s neck; the dog stepped on his stomach and made eye contact with him. Marco was panting and anxiously looking for something in the dog’s eyes. The skinny man came up and berated the dogs. He dragged the wolf-dog out with one hand and kicked it in the haunches. Wagging its tail, the dog looked at its master and left grudgingly. Marco clambered up and scuffled with the man. The man started to return the blows, and then stopped, saying, “I’m dying.” His face turned paper-white and dripped cold sweat. Frightened, Marco helped him sit up against the wall. After quite a while, the man said, “My father died before I was born. I have a serious congenital heart condition.”

“You won’t die, will you?”

“I’m dying. But what will happen to the dogs? Who will they belong to… belong to… ah!”

He rolled his eyes, struggled a few times, and then gradually revived again.

“Who are you?” he asked Marco weakly.

“I’m that Dutch dog.”

By now, the dogs had all left the dining hall. There weren’t any outside, either. No one knew where they’d gone. Little Leaf dashed up and said that something had been stolen from the kitchen in the back: a large slab of beef had disappeared right under her nose. The manager had reported it to the police. The moment the man heard this, he stood up and limped out.

He walked unsteadily, but didn’t stop. And thus he disappeared from everyone’s line of vision. The manager said, “I know him. He always goes to a lot of trouble for these dogs. They’re his life.”

One day as they sat in the kitchen at break time, Little Leaf and Marco saw the stolid old man planting something in the wasteland. He dug a hole with a rake, took a seed from his pocket, and buried it in the hole. Then he took a few steps forward and dug another hole. . . The wasteland had sandy soil that didn’t hold water, and so hardly anything could grow in it. What had the old man planted? “It’s something that dropped from a human body,” he later told Marco. But what he took out was seed-shaped—a little round, grayish-blue thing. How could something like that fall out of a human body? Later, the old woman showed up, too, and helped him plant. They were busy for a long time. Marco said to Little Leaf, “I told you they were together, didn’t I? They used to come to dine separately and pretended they didn’t know each other. In fact, they always communicate with each other.”

The next day, the two reappeared. They had sown the entire wasteland with that thing. Supporting each other, they stood taking stock of the results of their work. They didn’t look at all happy; they looked melancholy. The old woman in mourning covered her face with her hands. They couldn’t tell if she was crying. Little Leaf ’s curiosity got the better of her and she wanted to go over for a better look. Marco held her back. He thought that in Holland, the two of them had owed one another a lot. Now they were paying each other back. Marco knew everything.

One moonlit night when Marco wasn’t present, Little Leaf ran over to the wasteland by herself and raked open a hole. After searching a long time, she found a grayish-blue seed. She examined it in the moonlight. From any possible angle, it was nothing but a stone—round and smooth and very hard. There were also vein lines on it. She buried it and raked open another hole, where she found a similar stone, maybe a little flatter and a little brown-colored. Such a large stone couldn’t have come from a human body, so why had he said that it had? After reburying the second stone, Little Leaf panicked and ran the whole way back to her living quarters. When she reached the box where she and Marco lived, she noticed several people craning their necks and looking at her from the other boxes. Marco said bitterly, “You’re really headstrong.”

Late that night, Little Leaf screamed because she distinctly felt her body falling apart—falling apart into many little pieces. Only her head remained intact. And her mouth was still able to scream. Her head floated in midair. She saw Marco busying himself in the wooden box, holding up a candle, picking up those little fragments (who knows why there was no blood?) and piecing them together. He did this conscientiously, inspecting everything carefully lest he miss something.

“Marco?!”

“Oh, baby, I’m here.”

Little Leaf was worried: Would Marco bury these little pieces in the ground? Marco urged her to go to sleep, and—in midair—Little Leaf closed her eyes. But she couldn’t sleep. In a haze, she again saw Marco bustling around. Somewhere, a cuckoo bird was calling: it was midnight. She didn’t know what Marco was doing. Suddenly, her hand felt very weak, like an infant’s. She tried to grab a glass from the table, but she couldn’t. She heard Marco talking.

“I came home and didn’t see you. I just knew that you’d gone to the wasteland and turned over those seeds. You had to relive that person’s experience. I’ve just figured it out. The gardener raised the cuckoo bird. See: he has raised just about everything here. He raised those China roses, and they all blossomed as large as basins.”

Then the candle went out, and Marco continued bustling around in the dark. He seemed to be sewing. Was he sewing those fragments together? If he had buried a few small pieces in the ground, what would have happened? She heard him say, “This is Holland’s border.” His voice was a little eerie.

Little Leaf couldn’t fall asleep until the first rays of dawn entered the box. She slept in through the day and didn’t go to the restaurant. While she was sleeping, their neighbors saw two older strangers circling around her box numerous times—taking careful stock of it. The neighbors saw the old woman lift a large black watch toward the sun and wind it up. The neighbors were bewildered: Why did she have to face the sun to wind a watch?

After a day of rest, Little Leaf returned to work feeling refreshed. When she entered, the manager was sitting at the entrance smoking a water pipe. He gave her an artificial smile and said, “Have you recovered so soon? Are you sure you’re all right?”

“What? I wasn’t sick. I simply overslept. Really…” She was flustered.

“You overslept? That’s okay. It could happen to anyone.”

The customers hadn’t yet arrived. She started her day by cleaning the dining hall. The restaurant was rather desolate. After cleaning for a while, she set the tables. The manager told her they would have no business today because there’d been a free reception the day before and the customers had all filled up then.

“It was a great day of rebirth for everyone,” he said.

Little Leaf looked up: the picture of the “sail” had disappeared from the wall. In its place was a birdcage. She looked again: the other picture was also gone. On the wall was a white rectangle where the frame had hung. Little Leaf contemplated this for a long time. The silence all around seemed to be warning her of something—but what? She went to the kitchen and then to the storeroom: she was looking for Marco. In the back of the storeroom, a door led to the wasteland. Little Leaf looked out. She saw Marco bent over raking those holes.

“Are you wrecking their hard work?” Little Leaf asked with a smile.

She noticed that he had dug up seeds from most of the holes. She didn’t understand why the little grayish-blue stones became black in the bright sunlight and lost their round shape. They were no different from ordinary stones. Were these the seeds the old man had planted? Marco was still digging energetically: he said he wanted to find a Holland pea. When Little Leaf asked what a Holland pea was, he said, “It’s a person’s heart.” He kept turning over the soil, but what he found were only the same black stones. He was sweating and depressed. Little Leaf realized he never forgot his days in Ho land, yet as she saw it, past events were like narrow, dark little alleys; it was hard to say where they would lead. Little Leaf felt vaguely threatened.

At last, he dug out a little round stone that was slightly larger than the others. In the sunlight it remained grayish-blue. When Marco held it up to look at it, Little Leaf heard the slight noise of an electrical discharge in midair. Marco blanched, and in a split second he became a different person. He said to Little Leaf, “I have some property in Holland that I haven’t taken care of. Tomorrow I’ll meet with people in the tax office. They’re pursuing me all over the world. I’ve bought a train ticket. I’ll set out tomorrow.”

Little Leaf smothered her laughter and asked, “Are you an alien?”

“Yes. Even I think it’s strange. Why have I stayed in this country so long?”

He threw down the stone and rake and gazed ahead. Then he clenched his teeth and walked away without looking back. He was heading to the city. Was he looking for someone else to talk to? Little Leaf detoured around the wasteland, and the sweet time she spent with Marco in the park archives kept flashing through her mind.

The manager appeared at the door to the storeroom. The smoke he puffed out from his water pipe blocked her view of his face. Little Leaf thought he was observing her. She walked toward him.

When the manager suggested that they sit beside the river for a change, Little Leaf agreed. Taking a cinder path, they reached the poplar trees on the riverbank. They had no sooner sat down than Little Leaf saw a beautiful woman dressed in a red skirt come up from the river with a sheep. The red and white color combination was very attractive.

“Who’s that?” Little Leaf asked the manager.

“She’s related to the old man who opened up the land behind our restaurant. I’ve seen her several times. Each time, she brings a sheep here and then slaughters it. Another time, I saw her sleeping on the sheep’s dead body. She’s really a tough girl!”

As the red and the white walked into the distance, Little Leaf still felt great admiration.

“Have you seen her slaughter a sheep?”

“Yes. She’s quick and nimble. Oddly enough, the sheep couldn’t seem to wait: it came over to her with its neck stretched out.”

“Oh!”

Little Leaf looked at the black river with grief-laden eyes—disturbed again by Marco’s behavior.

She asked the manager if it was possible for one to be psychologically transformed into another person and never change back. The manager asked if she meant the man in the river. Little Leaf saw a small boat sail past with an old and lonely fisherman on it. Little Leaf had never seen this white-bearded old man.

“He’s the only one who couldn’t return to his original self.” The manager’s voice rang out in midair.

“I’ve been here a long time. Why haven’t I ever seen him?”

“Ah, he’s always in this river, but not everyone can see him.”

Little Leaf thought this was a strange day: she had seen two odd things. Were they connected with Marco’s metamorphosis? In a split second, she had become fascinated with this black-colored river. It was a gently swaying world that would inhale her. She sighed deeply, and her eyes filled with tears. The old fisherman sailed past, and a strange scent blew in on the breeze. All at once, she thought of the tropical garden.

“Is he the gardener?” she asked, glancing suspiciously at the manager.

“Yes,” the manager nodded. “He is. This river looks black to you, but actually it’s as transparent as crystal. Have you ever seen crystal? It’s exactly like crystal.”

Little Leaf took her leave of the manager and walked quietly toward her box. She saw the old man’s boat go past again, this time upstream. He was rowing it. After sizing him up at close range, Little Leaf thought he didn’t seem as old as he had just a while ago. Though his hair and beard were white, his eyes were bright and expressive, his arms still muscular. She couldn’t believe he was the gardener, because the old gardener who lived in the wooden box over there was so old that he couldn’t even walk steadily. But when she took another look, she felt that this old man in the river did resemble the gardener a little. Could they be relatives?

And so it was that the two of them—she on the bank, he in the river—moved ahead at the same speed. When Little Leaf reached her wooden box, the old man was pulling the boat ashore and tying it to a tree. He rushed toward his own wooden box, and Little Leaf finally believed that this one was indeed that one. Then was he the legendary immortal? The sunlight on the river hurt Little Leaf ’s eyes. She burrowed into the box. Marco was sleeping on the floor.

In the dark, Marco said to Little Leaf, “How come I’m still here?” Little Leaf started to laugh. She answered, “The manager told me that only the gardener had changed permanently into another self. But he can change his age and become young again: I saw this for myself today. He can also sail a boat: he’s exactly like a young person.”

“But I’ve bought my train ticket. I leave tomorrow.”

Ignoring him, Little Leaf picked up some garlic and green vegetables, as well as cooked meat that she had brought back from the restaurant, and went out to the shed to cook.

While she was cooking, she heard Marco shouting, “I’m an alien!

Didn’t any of you know that?!”

Little Leaf heard rustling noises outside the shed. She whipped open the curtain and saw the old gardener. He was the same as before—a humpbacked man with glaucoma. He said something obscure and motioned several times. Little Leaf finally realized that he was asking for a bowl of food. She gave it to him, and he sat on the rock outside and ate. He was toothless so he ate slowly. He closed his eyes as he chewed, as if falling asleep. Then Marco came over, and the three of them ate together on the large rock. In the sunshine, each of them was preoccupied. For some reason, Little Leaf looked a bit distracted. She felt that at this time and in this place, she had become a lady of ancient times who was painting on rice paper. As far as the eye could see, dragon boats were racing in the river.

Can Xue is a pseudonym meaning “dirty snow, leftover snow.” She learned English on her own and has written books on Borges, Shakespeare, and Dante. Her publications in English include The Embroidered Shoes, Five Spice Street, Vertical Motion, and The Last Lover, which won the 2015 Best Translated Book Award for Fiction.

Karen Gernant professor emerita of Chinese history at Southern Oregon University, translates contemporary Chinese fiction in collaboration with Chen Zeping. Among their translations are: Can Xue, Blue Light in the Sky and Other Stories (New Directions, 2006); Can Xue, Five Spice Street (Yale University Press, 2009); Eleven Contemporary Chinese Writers (Turnrow Books, 2010); Can Xue, Vertical Motion (Open Letter Books, 2011); Zhang Kangkang, White Poppies and Other Stories (Cornell East Asia Series, 2011); and Alai, Tibetan Soul (MerwinAsia, 2012).

Chen Zeping professor of Chinese linguistics at Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China, has written more than thirty articles and papers for professional journals and international conferences, and has also published numerous books in his field. He has also taught at Southern Oregon University and at Ehime University in Matsuyama, Japan. In 2005, he received a fellowship from the Japan Foundation for the Promotion of Science to present a series of lectures in Japan. He returned there to present lectures in early 2008.

This excerpt from Frontier is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Translation Copyright © 2017 Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping.

Photo: Can Xue, private

Photo: Chen Zeping, private

Photo: Karen Gernant, private

Published on February 1, 2017.