Translated from the French by Jordan Stump.

The late 1950s:

A childhood disturbed

I was born in the southwest of Rwanda, in Gikongoro province, at the edge of Nyungwe forest, a large high-altitude rainforest, supposedly home—but has anyone ever seen them?—to the last African forest elephants. My parents’ enclosure was in Cyanika, by the river Rukarara.

Of my birthplace I have no memory but the homesick stories my mother told all through our exile in Nyamata. She missed the wheat she could grow at that altitude, and the gruel she could make with it. She told us of her battles with the aggressive monkeys that ravaged the fields she farmed with her mattock. “Sometimes, when I was young,” she would say, “I joined the little shepherds tending the cows at the edge of the forest. Often the monkeys attacked us. They walked on two feet, just like men. They wouldn’t put up with my little friends’ insolence. They attacked them. They wanted to show them that monkeys are stronger than men.”

My father was not an aristocrat with vast herds of cows, as some people think of the Tutsis. Still, he knew how to read and write, and he’d learned Kiswahili, the language used by the colonial administration, so he worked as an accountant and secretary to sub-chief Ruvebana. But he was a real jack of all trades: he managed his boss’s assets, and when it was necessary he went to prison in his boss’s place. He was serving a sentence for him when my oldest sister Alexia was born. That earned her the slightly odd name of Ntabyerangode: “Nothing-is-ever-completely-white.” Which, to my father, meant that the joy of his daughter’s birth had been somewhat spoiled by his incarceration. Sometimes, too, my father Cosma went hunting for gold in the torrents of the mountains on the Congolese border. He came home with a few little chips, in matchboxes. We never got rich off those tiny flakes.

In 1958, sub-chief Ruvebana was appointed to Butare province, and my family followed him. The sub-chiefdom was located in the far south of the province, on the crests overlooking the valley of the Kanyaru, whose course forms the border with Burundi. From our new house, in Magi, on the steep foothills of Mount Makwaza, we had a sweeping view: the valley of the Kanyaru and its papyrus swamps, and, beyond, much of the Ngozi province in Burundi.

Mount Makwaza was the homeland of a great Hutu chief, an igihinza. We were terribly afraid of him. My mother described him as a giant, always dressed in a leopard skin. When threatening clouds shrouded the mountaintop, she would tell us, “Someone must have angered the igihinza, be good now.” In our childish terror, we believed the igihinza’s enormous shadow was darkening the whole mountainside. No one dared venture out at the foot of Mount Makwaza after dark, for fear of disturbing the igihinza’s nighttime doings. Up at the very top of the mountain, we thought we could see the glow of his fire.

My big sister Alexia and my older brothers Antoine and André went to school. My mother worked in the fields. We rarely saw my father at home; he had an office, which still exists, facing the sub-chief ’s residence, but he didn’t spend much time there, because he was always out on his bicycle seeing to matters that I found deeply mysterious. My father had the only bicycle in the area, which gave him considerable prestige, reinforced by the pen sticking out of his shirt pocket, an uncontested sign of his authority. The moment they spotted him pedaling along the narrow mountain path, the village children would cry out “It’s Cosma! It’s Cosma!” and parade along beside him all the way to the house. Hearing those shouts, my mother would begin reheating the pot of beans and bananas she always kept ready for my father’s unexpected returns. I can still picture that pot, reserved for my father’s meals alone. It was tall, completely black but shiny inside, made of very thick cast iron. It was the only metal kitchenware we owned. It had a name: Isafuriya ndende, the “big cookpot.” My father told of buying it from a street-merchant in Zanzibar. It was a very precious object, so precious that my mother wouldn’t leave it behind when we were expelled from Magi. The famous cookpot followed us into our exile in Nyamata.

We were still living in a mud hut with a straw roof, but my father set about having a brick house built on our plot of land. He went into debt for it. My mother was apprehensive about moving into a house like the white people’s, or almost—an urutare, a “big rock,” as she called it. She still missed the warm intimacy of the hut she’d lived in as a child, a big hut made of artistically woven grasses.

As for me, I spent my days with the potters who’d set up their camp in the eucalyptus woods facing the house. They were Batwa, a people kept at arm’s length by the rest of Rwanda. The first Europeans called them Pygmies, very wrongly. Boniface, the patriarch of the “tribe,” welcomed me as if I were his own daughter, and my mother thought nothing of seeing me go off to play with the children of people traditionally treated as pariahs. She often gave me beans and sweet potatoes for the children, and in return the Batwa brought her their nicest pots.

—— —— ——

The first pogroms against the Tutsis broke out on All Saints’ Day, 1959. The machinery of the genocide had been set into motion. It would never stop. Until the final solution, it would never stop.

Needless to say, the anti-Tutsi violence didn’t spare Butare province. I was three years old, and that was when the first images of terror were etched into my memory. I remember. My brothers and my sister were at school. I was at home with my mother. All at once we saw plumes of smoke everywhere, rising up from the slopes of Mount Makwaza, from the valley of the Rususa, where Ruvebana’s mother Suzanne, who was like a grandmother to me, had a house. And then we heard noises, shouts, a hum like a swarm of monstrous bees, a growl filling the air. I can still hear that growl today, like a menace swelling behind me. Sometimes I hear that growl in France, in the street; I don’t dare turn around, I walk faster, isn’t it that same roar, forever following me?

My mother immediately lifted me onto her back: “Hurry, we’ve got to go get the children so they won’t try to come home.”

But just then a crowd appeared, bellowing, with machetes in their hands, and spears, bows, clubs, torches. We hurried to hide in the banana grove. Still roaring, the men burst into our house. They set fire to the straw-roofed hut, the stables full of calves. They slashed the stores of beans and sorghum. They launched a frenzied attack on the brick house we would never live in. They didn’t take anything, they only wanted to destroy, to wipe out all sign of us, annihilate us.

They almost succeeded. Nothing remains of my parents’ enclosure in Magi but a tall fig tree. I picked up a little fragment of brick from a pile of rubble—I’d like to think it came from our house. An old woman came running toward me from the banana grove, grumbling: Who is this stranger? What’s she doing prowling around the hut? I said nothing, unable to break in with a question while she went on and on, as if talking to herself. Suddenly I heard her say the name Cosma. Cosma? Cosma, yes, she remembered him, or she’d heard about him. But she wasn’t there the day my house was destroyed, she was sick, or maybe she was getting married. Why bring all that up again? It was so long ago. Had I come to drive her out of her little house?

I look at the tall fig tree. No, the killers hadn’t succeeded. My two sons are alive. They’ve seen the tall fig tree that preserves the memories, and like that tree they’ll remember.

I don’t know how my mother managed to get Antoine, André, and Alexia from school. We were all gathered together in the sub-chief ’s enclosure. The Tutsi families that had escaped the slaughter and whose houses had been burned had spontaneously come there to seek refuge. I believe my father tried to organize the crowd as best he could. After nightfall, we set out for the Mugombwa mission.

My brother André says it was Belgian paratroopers who oversaw the transfer. “Just to keep us in line,” he said, “one of them threw a grenade at a dog, and it was blown limb from limb.” From then on the Tutsis knew where they stood.

The refugees were housed in Mugombwa church and the classrooms of the mission. They stayed there for some two weeks. In my little-girl mind, I found it all wonderful. There were many, many people. The mothers cooked in the courtyard. My brothers and my big sister no longer went off to school. My mother no longer tended to the crops. The children played all day long, and we ate something we never had at home: rice! It was strange, everyone slept on the floor in the same room, even the parents! I wasn’t afraid anymore!

I went back to see the school buildings we’d been stuffed into. A far grander church was built next to them in 1976. In April 1994, the Tutsis took refuge there, or were driven there. I was told that Father Tiziano, as the people of Mugombwa called him, an Italian, locked the church doors with a padlock and fled to Burundi, declaring that everything would be fine. Today the tile roof, peppered with holes made by bullets and grenade shrapnel, has been replaced by a bold metal framework. On Sundays the church is full. How many murderers among the pious assembly? The faithful sing with all their hearts. Jesus is kind. He forgives all sins. He forgets everything. When Mass is over, the young people from a Catholic movement raise the Vatican’s gold and white flag, marked with the Chi-Rho symbol. Hand on heart, they sing a hymn to the glory of Saint Francis Xavier. Who would ever be so rude as to bring up the “unfortunate events,” as they’re called by those who deny all participation in the genocide and refuse to speak the word? Let us forgive each other, and let us go on as if nothing had happened.

—— —— ——

While I was playing in front of the school, some odd things were going on in one of the classrooms. As my brother explained it, all the family heads were appearing by turns before a sort of jury of Hutu notables. They decided who could stay and who was to be expelled. As it happened, all the Tutsis whose houses had burned were to be banished. Maybe they wanted to be sure there were no stray Hutus among the exiles.

One morning, before dawn, they brought us out of the classrooms. The schoolyard was full of trucks. I’d never seen so many. The motors were running. Their headlights blinded us. We heard shouting: “Into the trucks, faster, faster!” There was no time to gather the few humble belongings we’d managed to bring with us. My mother brought only the famous black cast-iron cookpot. That was our only luggage. I was crying. I’d lost my little milk jug, which I was never without. My mother held us close to her so we wouldn’t be lost in the commotion. I clutched at her pagne. We had to climb into the trucks, and quickly. We were crammed in like goats, all pressed together. We had to leave at once.

The trucks started off. A crowd had gathered by the side of the road to watch the convoy go past. Everyone was shouting, “There go the Tutsis,” and they spat at us, waving machetes.

At first, I wasn’t unhappy: a trip in a car was a novelty for me. But the journey turned more and more unpleasant: it went on forever, we were so tightly packed in, we crashed together with every bump in the road, we had to struggle not to suffocate, we were thirsty, there was no water. The children were crying. Whenever we drove by a river or lake, the men beat on the roof of the driver’s cab to ask him to stop. But the trucks kept on going. Night had fallen. No one knew where we were headed. I saw despair in my mother’s eyes. I was afraid.

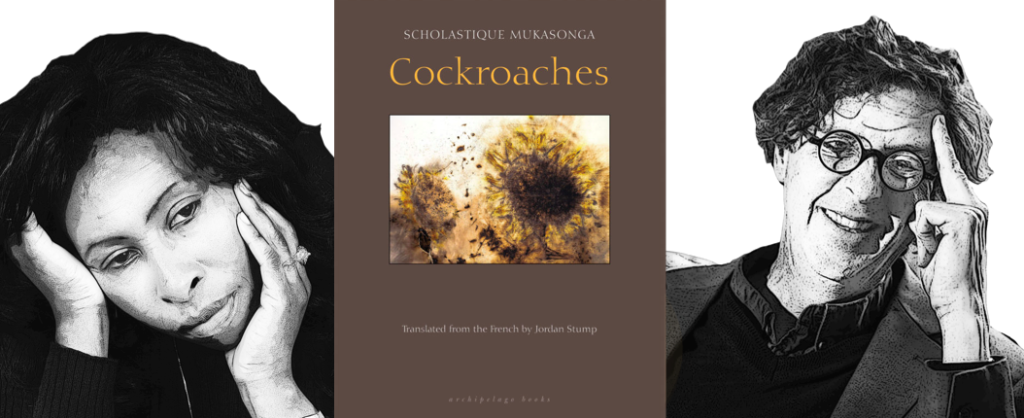

Scholastique Mukasonga is a Rwandan writer. Her first memoir Inyenzi ou les Cafards, marked Mukasonga’s entry into literature. This was followed by the publication of La femme aux pieds nus in 2008 and L’Iguifou in 2010, both widely praised. Her first novel, Notre-Dame du Nil, won the Ahamadou Kourouma prize and the Renaudot prize in 2012, as well as the Océans France Ô prize in 2013 and the French Voices Award in 2014.

Jordan Stump is the author of articles on the Marquis de Sade, Georges Perec, Marie Redonnet, and Jean-Philippe Toussaint, among others, and of Naming and Unnaming: On Raymond Queneau (University of Nebraska Press, 1998). He has also published translations of novels by Marie Redonnet, Eric Chevillard, Patrick Modiano, Christian Oster, Antoine Volodine, Jean-Philippe Toussaint, Jules Verne, and Honoré de Balzac. His translation of Claude Simon’s The Jardin des Plantes (Northwestern University Press, 2001) was awarded the French-American Foundation’s annual translation prize in 2001, and in the fall of 2006 he was named Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. His interests include literary theory, the contemporary novel, the ontology of fiction, and literary translation.

This excerpt from Cockroaches is published by permission of Archipelago Books. Copyright © 2006 Scholastique Mukasonga. Translation copyright © 2016 Jordan Stump.

Photo: Scholastique Mukasonga, Private

Photo: Jordan Stump, University of Nebraska

Published on December 12, 2016.