Translated from the German by Chenxin Jiang

The Alps form a crescent that stretches across Europe like a croissant-shaped Kipferl. Within these mountains lies Switzerland, shaped like a round bun, and Switzerland is Europe. Switzerland is disintegrating into its valleys—there is such loneliness on the mountaintops! (Kipferl isn’t a word that all people know; nor is Gipfeli, the Swiss-German word for a croissant; there isn’t anything that people all over Europe know.)

Europe is disintegrating, the old lady is falling apart. She recently appeared at the Museum Festival with a terrible heap of jewelry around her neck; she’d just dyed her hair blond; above her fake gold necklace hung her wretched, worn face, and then she laughed, walked up to the bar, embraced a tall young man, and drew him up to her lips to kiss him artfully.

Europe consists of its disintegration. Europe is disintegrating into its individual valleys. The valleys are boundaries dividing one mountain from the next, each mountain from the others. And the old lady looks frightful. Europe has high, high peaks with valleys between them, and the mothers drive their children into the ravines, up to the cliffs. They say that a different people lives in each valley; a few years ago they had only four languages between them, but since then they’ve further divided the languages, each valley has a language, there’s still only one language per valley, but soon there will be many more, as time passes and everything matures. All kinds of accents and even all kinds of words lie in the wrinkles, the valleys, if Switzerland is Europe. Eventually (this word is common to all the valleys), every person will be recognizable by her language, by the attitude of her mouth. Even to the north and west of this country, the timbre of a voice can function as a geographical clue, as in the warring southeast, where people create distance between themselves via accents; creating distance via dialects happens here too, all kinds of sounds set the tone in mountains, caves, and lakes.

A collection of wrinkles, mountain ridges wrinkling the earth.

But now that all the roads are being rebuilt constantly, the roads themselves are carving a constant course toward a great continental future. Office buildings gape emptily from the curb, peering down at the streets until the streets are razed and moved elsewhere and everything that was in them has been swiftly rearranged; streets coursing all the way to the borders and up into the mountains as well, into a future with new streets that lead into all the valleys, the valleys in which these most diverse languages are spoken.

No one can learn more than two or three of these languages, and people only retain things they can actually grasp, but the accents are gliding further and further apart, especially the vowels, as though the vowels weren’t open sounds but private ones, so that there’s barely a single word that everyone in Europe knows. Of course everyone keeps trying to learn as many words as possible, but that isn’t easy when people barely understand and often misunderstand each other.

A collection of languages. Words drop out, fall out of use, and when they do, you may never again be able to say the things those words meant.

Collecting junk is part of collecting languages, all kinds of junk; of course there are no figures for how many pairs of pantyhose are torn in Europe each day, and the past and future of interesting and uninteresting items of clothing remain obscure, although these things should have a say, and not only because they create so much junk.

Sunset. It is evening.

At the Museum Festival not too long ago she said she wanted to be overwhelmed. She was soon overwhelmed, because portraits of her were hanging on all the walls, even if these portraits of her as a young woman represented nothing more than the artists’ imaginations. Nonetheless, there is something unmistakable about Europa, about the sudden eruption of her expansive gestures. No matter how old she is, she still tries to surprise with her eruptions.

She is bruised, formed like lava, old, ugly, yet still alluring, an extremely opaque lady, not really a lady, but a woman. Little is known about her emotional life, and she remains adamantly silent on that point.

To put it in more technical terms:

He (whoever he is) was born in Hamburg and then lived in Munich; he was born in Hamburg, spent two years in Paris, and then moved to Rome, a Hamburger. He was born into the world in Hamburg, but he lived in Kiev, and then later in Mělník, which made him Czech; he lived there for a while—the Hamburger was a Czech—and some years later he went to Rome. ftere, one evening, he met the man who had been born in Zurich and lived in Geneva; the Genoan arrived, and it was a significant evening for both Romans. ftey arranged to meet again in Graz, and the wife of one of the two Romans also came along; she was not Roman and had never been to either Rome or Hamburg, but was born in Baar and grew up in Ticino, and now she was driving with the two Romans to Graz, which made them all Austrians. It goes without saying that someone from Hamburg has had quite different experiences than someone from Switzerland—where you belong isn’t a matter of indifference—but they decided to travel to Italy together, and at the border they met an American woman who noticed the extra spot in their car and wanted to join them. Now there was an American sitting next to the Austrians. Having spent three weeks in America, she was busy readjusting; she kept referring to jet lag in English, but the Austrians couldn’t understand the American because she had a French accent. You can get used to an accent, of course. They arrived in Genoa, those Genoans.

As he was speaking, three women from newspapers and two from magazines stood next to him, taking notes and waiting for the interview that would follow, while the artists’ wives were also waiting and pinning up their hair, and then the photographers came. But things hadn’t gone that far yet, it was a very long process. It must be said that his speech made his listeners feel at home: the gallery owners were nodding, the women from the newspapers and magazines took more notes, and the artists listened. fte artists had arrived almost on time, so they had been able to catch the beginning of the speech, and even their wives, insofar as they had come with their wives, were listening—it’s a woman’s job to listen—and the women from newspapers and magazines naturally took notes so as to later ask relevant questions in their interviews with the artists; the talented gallery owners were silent, and the speaker spoke in such a way that even the artists listened, as well as their wives, insofar as they had come with their wives; the art historian was there, as well as the gallery owners, remaining silent about their own talents, while the women from the newspapers and magazines took some notes, and that’s when the photographers came, while the artists listened cautiously, their faces turned toward the speaker, who was slowly arriving at the end of his speech, and their wives, insofar as they had come with their wives, were laughing—it’s a woman’s job to laugh—pinning up their hair, when the photographers arrived, and as the master of the room slowly got to the end of his speech, it struck him that one of the artists’ wives was pretty to look at, and all that while the women from the newspaper were cautiously noting down what he said, waiting for the interview to begin, while the artists, standing next to the gallery owners, bowed their heads, so that the gallery owners looked at the wives . . .

Next to the door stood a man who had nothing to do with this crowd and didn’t feel at home among them; he looked as though he would rather be elsewhere; he was easy to overlook, which is to say that he didn’t blend in, he blended out, a man with a southern face, probably a Roman. She lay on a slate slab, propping herself up with one elbow, and for some reason she put up her hair with her other hand, the woman from Hamburg. In the meantime she looked into the milky sun, barely aware of her own feelings. ftree men, artists, were hard at work doing portraits of her.

Of course Europe is a collection of languages as well as wrinkles, and love is part of every collection. In this sense Europe is a love story too.

Despite her age, and despite the fact that no one wants to look into her bitter face, she’s never considered backing down. Her rightful place is where she’s standing, as she pointed out recently at a demonstration where many women gathered.

It isn’t true that Europeans don’t want to be loved; Europeans want love, and when this desire isn’t fulfilled, war breaks out. ftis desire is never fulfilled.

Whenever Europeans are bitterly unloved, they go shopping, and then they can see: that’s where love has gone. In Spain at least there are bullfights, people ask themselves where the bull comes from and look at him, and that’s interesting; it’s very European (which is to say: very much Europa), you can hardly imagine Europa or Europe without bulls.

But the story of the bull goes way back. Although much has changed since then, many women still have a bit of Europa in them (which means they’re either afraid of bulls or love them, Hemingway has already said everything else there is to say about these powerful animals).

In this wrinkled collection of a continent certain words remain unintelligible. If those words are translated anyway—and it’s one of the most wonderful of European accomplishments that they so often are—the view becomes clearer, and now you can see a huge, green, mossy, steep field, beneath which there are streets running through the mountains, and cows and bulls grazing separately on the fields. Cows, bulls, mossy fields. As it flies over the landscape from east to west, trailing a dark shadow far beneath it, the plane makes the landscape smaller.

fte fact that so much is translated is one of the most wonderful European accomplishments, even though translation so often leads to misunderstanding.

Not long before the outbreak of the war in Yugoslavia, a young Slovene found a package somewhere near Sarajevo. In an attic. It contained several notebooks and loose bits of paper, probably Europa’s latest notes and diaries. ftey were fragmentary, unpublished private jottings. Here follows an excerpt from this material:

I very much doubt that European languages will simply drift apart. Quite the contrary. When else have there been so many words that mean the same thing in every country, even if they don’t mean much on their own? Everyone understands the words stop, go, and okay, as well as so many other signs, signals, symbols, icons. I only wonder how it’ll ever be possible to talk about these symbols. Right now this is the most pressing question I have.

It makes no sense to appear as a bull when people are expecting a swan, but he had to attempt to appear as a bull. And it wasn’t honest of him to be passing himself off as a bull, he made a dishonest start, since he was only imitating the sort of bull that remains a bull under all circumstances.

Being a real bull, which he certainly wanted to be, would have been more honest.

According to my name I’m a European and I have no intention of backing down. On the contrary, I want to name everything after me. In the beginning only a tiny stretch of eastern Europe had my name, but the term spread westward, into the sunset, until my name stretched from the Urals to the ocean. ftat wasn’t how it was in the beginning: the somewhat hidden root of my name is actually Erev, meaning sunset, the evening laying itself down upon the earth, the sun setting toward darkness. Erev, calls the young man at the bar; I’ll never let him go; I know what I’m entitled to, and he knows all too well that the darkness and sunset he’s been dreaming of won’t stop at the ocean, it’ll cross over to the next continent, where they also speak my languages; America has long belonged to me, and I will proceed further westward, across the next ocean, westward to Asia, where I’ve already arrived, till I end up where I’m from. (Or rather, something that started with me will end up there, but I don’t claim to know precisely what.)

And I think there’s also a technical way of describing this: My name is Erev, and my memory remains good as I keep going, full of wrinkles and folds, all the way back to Asia. fte young men will keep that in mind, talented as they are, while the young women will turn resolutely away in disgust, but they too will grow old and so grow either subdued or talented. fte women from the newspapers and magazines stand on one side with the first wrinkles, and the men stand on the other side. And over there, on the other continent, they speak my language, and during my speech, which is still about the powerful or about power or sometimes also about bulls, the gallery owners are pinning their hair up, and the artists and their wives, or at least the ones that came with their wives, are listening attentively. I go on speaking, my speech is currently about Geneva—I am Genovese—I’m speaking calmly to artists and women on the subject of rubble, collecting rubble in Switzerland, on the dialectical disintegration of languages and of other collections, I’m pinning my hair up and waving with both hands at the young man over there, while here, in this place, it grows dark, night has come.

I have to get a facelift. It’s not that I used to be much better looking when I was younger. Ancient crones are hideous, I know, at least some of them are, but gradually, gradually, they can begin to look less ugly.

A thought looks like a knot. Just like Kipferls or buns, thoughts have a certain correct form, a real form that has neither beginning nor end and is visible from every angle. And the form of a thought, although thoughts all look different, doesn’t really have a beginning, thoughts run their course, they run in different directions, even if they will always be knots, and besides, even Europe has an external form without beginning or end, as Europe runs westward toward Asia.

I feel at home in Asia. I just took a look in the mirror, I don’t like that young man anymore, and I absolutely must collect myself.

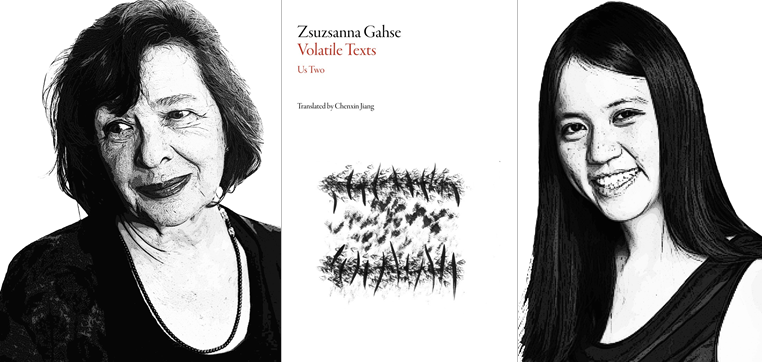

Zsuzsanna Gahse was born in 1946 in Budapest, from which she fled with her parents to Austria during the 1956 revolution. She grew up in Vienna and Kassel, and currently lives in Switzerland. She has published twenty-five books, and has translated the works of Hungarian writers such as Zsuzsa Rakovszky und István Vörös into German. Recent works include JAN, JANKA, SARA und ich (Edition Korrespondenzen, 2015) and More Than Eleven, an opera libretto for mezzosoprano. She has received numerous prizes for her work, including the Aspekte-Literaturpreis (1983) and the Adelbert-von-Chamisso-Preis (2006). Since 2011 she has been a member of the Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung.

Chenxin Jiang is a literary translator based in Chicago and Berlin. She translates from the German, Italian, and Chinese; recent and forthcoming translations include French Concession by Xiao Bai for HarperCollins, The Cowshed by Ji Xianlin for New York Review Books, and Volatile Texts: Us Two by Zsuzsanna Gahse for Dalkey Archive Press. She has received a PEN Translation Fund grant as well as the 2011 Susan Sontag Prize for Translation, an annual award made to one translator under the age of 30. Her writing and translations have appeared in Words Without Borders, The Nation, Pathlight, Poetry London, and on the BBC. She is a senior editor at Asymptote.

This excerpt from Volatile Texts: Us Two is published by permission of Dalkey Archive Press. Copyright © 2005 Zsuzsanna Gahse. Translation copyright © 2016 Chenxin Jiang.

Photo: Zsuzsanna Gahse, Ansichten

Photo: Chenxin Jiang, Paper Republic

Published on December 1, 2016.