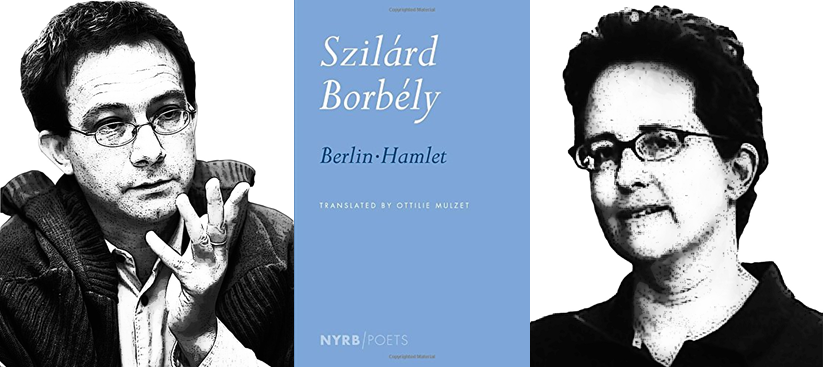

Translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet.

21. [ Kurfürstendamm ]

At the time I had no answering machine, so

I couldn’t call myself. Ludicrous, perhaps,

even morbid, how secure it made me feel to know

at any time I could hear my own voice. There is a voice, however

mechanical, which is mine. I have nothing else, if I think

hard about it, which is certain, just this distant voice

which comes from a machine. And the fact that at any time,

from anywhere, I can eavesdrop on it. There is a room, where

I live, and in it is a little black machine, which

speaks in the empty room. It makes clicking sounds. Now

spinning forward, now back. It switches on, then off.

It devours the room. But then I still had no

machine, and there was no one whom I could

have called. Who would have spoken to me, and I would not

have to feel ashamed for needing this voice. Just to hear

someone speaking to me. I concealed my faltering, whimpering voice,

my mask-like face with its wayward mimicry.

Perhaps it was on the KuDamm that I saw it in a shop window, reflected

back for the first time. What I could say

to it. Since then I have a machine, sometimes I call myself.

I patiently wait until the end of the message, and after the long whistling sound

I leave these words: “I will outlive you, you pipsqueak!”

25. [ Tiergarten I ]

The names of the streets, like the arid branches of the trees

in the park, which today is a labyrinth,

my path leads me across the Bendler Bridge,

Friedrich Wilhelm and Queen Louisa,

they too were here, but I have come too early,

chill circles dissolving into each other,

the Hofjägerallee is a disappointment,

amongst the foliage the maiden Ariadne,

then she disappears again behind a kiosk,

if I could only be Louis Ferdinand,

the prince of the narcissus and of the crocus,

Luise von Landau has invited me

to tea, on the banks of the Lützow, then

across the bridge, facing the gardens,

where friezes stand on the facades of the houses,

caryatids, Atlases, stair-carpets,

the cherubs and the Pomonas, the stained-glass windows,

the door-knockers, the battered threshold gods,

all admit me, the veil of Ariadne

flutters here, the silent seeds planted

thirty years ago in this garden and the paths

covered with thicket and now there too

are the Lernean Hydra and the Nemean Lion

somewhere, near the Grosser Stern, while

the rising breeze from Europe’s past

slowly propels with the dreams of the Hesperides

the laden vessels upstream

on the Landwehr-Canal, and the sailors’

hearts are filled with the anguish of times gone by,

as they moor at the bridge of Heracles.

39. [ Fragment VIII ]

I can no longer bear the aggressiveness of poetry,

and I do not wish my deeds to be investigated.

I would like to be an opened knife: the inscrutable.

A razor-wielding murderer. With a tongue oozing flattery, who drips

poison into your ear. Who makes you mute, so you cannot

scream. As the guards turn into the corridor,

I count five steps. Now is the time to cry out. Before

they throw themselves on me. Then in the stillness, there are no sounds.

Szilárd Borbély is widely acknowledged as one of the most important poets to emerge in post-1989 Hungary. He worked in a wide variety of genres, including essay, drama, and short fiction, usually dealing with issues of trauma, memory, and loss. His poems appeared in English translation in The American Reader, Asymptote, and Poetry. Borbély received many awards for his work, including the Attila József Prize. He died in 2014.

Ottilie Mulzet is a Hungarian translator of poetry and prose, as well as a literary critic. She has worked as the English-language editor of the internet journal of the Hungarian Cultural Centre in Prague, and her translations appear regularly at Hungarian Literature Online.

Photo: Szilárd Borbély, The Missing Slate

Photo: Ottilie Mulzet, Private

This excerpt from Berlin-Hamlet is published by permission of NYRB Poets. Copyright © 2003 Szilárd Borbély. Translation copyright © 2008 Ottilie Mulzet.

Published on December 1, 2016.