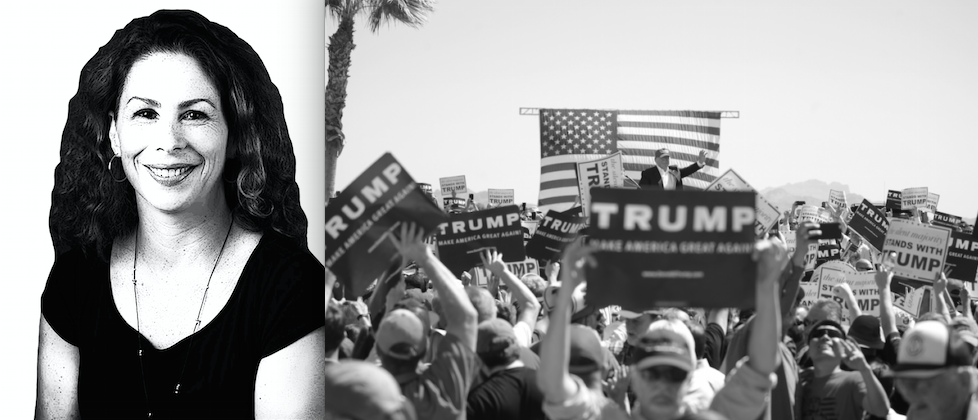

In the aftermath of the U.S. election, I sat down with Sheri Berman, professor of political science at Barnard College and chair of the Council of European Studies (CES). We discussed some recent transformations in European politics, and the possibility of creating sustainable political parties. Sheri had served as the discussant for an event at Columbia University’s European Institute on “Illiberal Populism in Europe,” which was the basis for our discussion.

—Jake Purcell for EuropeNow

EuropeNow The themes of the 2017 International Conference of Europeanists are sustainability and transformation. One transformation that you’ve spent a lot of time on recently is the current prominence of populist movements in Europe and the U.S. For our readers who missed the European Institute event, one definition of populism includes: anti-establishment tendencies (a rejection of elites, big banks, groups with privileged access to political power), a charismatic leader, and retrenching nativism that produces an “us vs. them” mentality. Following Brexit, in particular, commenters seem to explain populism as either a response to post-industrial economic insecurity or as a cultural backlash against newly influential progressive values. Pippa Norris argued in favor of the cultural backlash thesis, which, interestingly, also seemed to be the conclusion of many historians participating in a discussion on Brexit that EuropeNow covered recently. What do you think is the transformation the rise of populism highlights or reveals? And why is this change in the relative place of populist politics happening now?

Sheri Berman Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart have written an excellent paper on the relative import of economic insecurity and cultural fears in the rise of populism. Clearly, both issues or trends are important, especially having come together so powerfully since 2008. We must understand populism as a reaction to or consequence of the failure of mainstream politicians, leaders, and parties to offer significant sectors of their citizenries convincing solutions to their problems and responses to their fears. Populists thrive, in other words, only when traditional parties are unable to hold on to or respond to the challenges facing their societies. Especially problematic has been the decline of the center-left since it is their traditional voters, particularly members of the white working and lower middle class, and the less educated, that have provided disproportionate support for both Trump and populist parties in Europe.

EuropeNow How might we create a sustainable center-left, or stable political parties more generally? Or, is some kind of fragmentation inevitable when a party is faced with a challenge like incorporating a much broader demographic range and range of ideological perspectives?

Sheri Berman This is a very difficult and important question. In some ways, the economic issues are easier to grapple with than the social/cultural ones. Clearly, many voters hunger for a more forthright grappling with the downsides of trade and globalization than the center-left has provided in the past years. Center-left parties need to convince voters that they take seriously the downsides of globalization while not killing the goose that lays the golden egg, i.e. giving in to isolationism, over-regulation or other policies that will significantly dampen growth. That there are ways to do this in the twenty-first century is evinced by the relative success of some countries in getting through the last decade or so in fairly good shape, most notably Canada and Scandinavia.

The social and cultural issues are harder for the left to deal with, since here the fragmentation on the left is of longer standing and the differences between different voting constituencies harder to overcome. Since the 1960s the rise of progressive values has driven a wedge between younger, more liberal voters and older more traditional ones. The center-left has been more accommodating, programmatically, of the former, with its policies often ignoring or denigrating the concerns of the latter. It is clear that this is problematic electorally and democratically, since these older, traditional voters have been flocking to the populist right in both Europe and the U.S. The left must figure out ways to stay true to its inclusive and non-racist heritage, while also responding to the legitimate concerns of voters who feel society is changing in ways that they don’t fully understand or feel comfortable with.

EuropeNow In a TEDxNewYork talk you gave about a year ago, you make the point that it takes democracies a long time, and more than a single try, to achieve anything that resembles stability. I don’t mean to conflate the rise of populist political parties with the collapse of democracies into military rule, the latter of which was actually the subject of your TEDx talk, but I do think the comparison raises some useful questions. How great is the current deviation from the status quo of party politics, and what might the consequences be for democratic institutions within individual countries? How far do events like Brexit in the UK or the election of Trump in the U.S. strain institutions?

Sheri Berman It’s important to remember that like history more generally, democracy develops cyclically rather than linearly. What we are experiencing now in the West is a period of real democratic discontent, perhaps even “deconsolidation.” Existing institutions are not working well, mainstream parties are losing support, extremism is on the rise, and illiberalism is enjoying growing support. For those of us concerned with Europe or democracy more generally it is important not just to assume that things will automatically get better. We need to figure out ways to make democracy more responsive and efficient or people will increasingly consider alternatives to it.

EuropeNow I was recently perusing the October issue of the Journal of Democracy, which was dedicated to populism in Europe and to which you contributed an essay. I noticed that the journal was particularly insistent that populism is not new, to the extent that previous issues of the journal had been devoted to the subject in both 2012 and 2014. Is there anything substantially different about the shape of populism now? Is the conversation about populism different in 2016?

Sheri Berman Populism has grown increasingly prominent over the past decades but it is a phenomenon that has been brewing for quite a while. The “traditional” party systems of the postwar period were changing already by the 1970s, i.e. during this decade we already saw a decline in class voting, support for parties of the center-left and right, and the rise of new parties (e.g. the Greens). So what we are seeing today is the high point of a trend that has been underway for a while. The question is whether there is any going back or if populism is here to stay.

EuropeNow Now that a political movement that shares many features with European populism has obtained political power in the U.S., what does it mean for how traditional party politics operates?

Sheri Berman I think we can expect to see significant changes in both the Democratic and Republican parties. As with their counterparts in Europe, they will have to grapple with the growing anger and discontent evident in large parts of the electorate. If they don’t, they will just continue to lose support to other, probably populist-style parties and movements on both the left and right.

Sheri Berman is a professor of political science at Barnard College and the chair of the Council for European Studies. Her main interests are European politics and political history, democracy and democratization, globalization, and the history of the left. Her two books have examined the role played by social democracy in determining political outcomes in 20th-century Europe.

Jake Purcell is the History in Action Research Associate at the Council for European Studies and a Ph.D. candidate in medieval history at Columbia University.

Published on November 11, 2016.

Photo: Sheri Berman, Barnard College

Photo: Donald Trump with Supporters, Gage Skidmore | Flickr