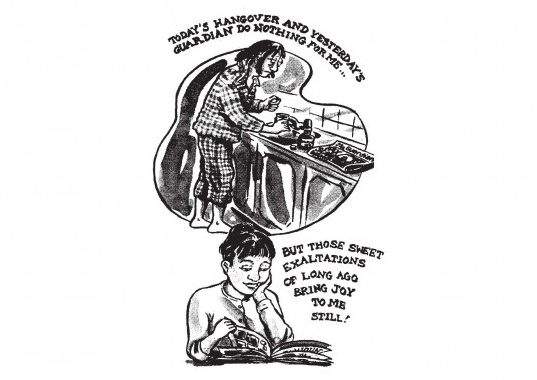

Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood by Mel Gibson

In focusing on the readership patterns of comics among British girls in the second half of the twentieth century in her monograph Remembered Reading, Mel Gibson recuperates a richly textured subject that has, by her account, “been largely neglected as a research subject within the academy and in popular accounts of youth culture” (2015, 175). This neglect emerges not only from the fact that she studies girls in a field known for marginalizing female experience, but also from her focus on Britishness.

This neglect emerges not only from the fact that she studies girls in a field known for marginalizing female experience, but also from her focus on Britishness.

While European comic cultures like France receive wide acclaim and scholarly interest, British comics are often overlooked—a fact echoed in other accounts of British comics, like James Chapman’s British Comics: A Cultural History (2011). In her own work, Gibson pinpoints this disregard in the reading practices of the women she studies. For some of these women, Gibson shows how foreign-produced comics, particularly American, at times captivated them over and above British comics. Due to this neglect, Gibson’s project becomes not simply an account of this topic, but also a study of why this area has been ignored and how this undervaluing erases lived experience and makes this research difficult.

Although Gibson covers a range of domestic and foreign comics that British girls read across the postwar period, she particularly focuses on domestic girls’ comics. This industry, active from the 1950s to the 1990s, produced titles like Bunty and Jackie that were about and aimed at young British girls. Despite the popularity of these titles in their time, and the nostalgia for them in the years thereafter, Gibson contends with the rarity of these comics today—in fact and in discourse. To contextualize why comics in general have been sidelined by criticism, Gibson spends the third chapter surveying how a range of academic fields have treated comics, chronologically moving through historic treatments—like 1950s-era moral panics and 1970s feminism—to more contemporary considerations (2015, 71–96).

To contextualize why comics in general have been sidelined by criticism, Gibson spends the third chapter surveying how a range of academic fields have treated comics, chronologically moving through historic treatments—like 1950s-era moral panics and 1970s feminism—to more contemporary considerations (2015, 71–96).

She ends this chapter by discussing the growth of research on girls’ culture within media and cultural studies, the space within which her main interlocutors—Martin Barker, Angela McRobbie, Valerie Walkerdine—have produced earlier accounts of girls and comics (2015, 91–96). Parallel to Gibson’s work, McRobbie’s research has been pivotal to the recent formation of girls’ studies; Mary Celeste Kearney uses McRobbie’s co-written essay, “Girls and Subcultures” (McRobbie and Garber 1976), as a point of departure in her study of contemporary American girls’ culture, Girls Make Media (2006), and in her later essay about the field, “Coalescing: The Development of Girls’ Studies” (2009). And, yet, despite this heritage, neither Kearney’s writings nor a more popular contemporaneous account of the field, Elline Lipkin’s Girls’ Studies (2009), discuss comics as an object of research. This lack of attention within the field most hospitable to Gibson’s work demonstrates the need for this work not only here, but across the multitude of fields that Gibson positions her research.

In the other four chapters, Gibson considers her topic from multiple perspectives, balancing the biases against comics in general and against girls’ comics in particular, which she identifies in the third chapter and elsewhere throughout the book. In surveying past assessments of British girls’ culture in her first chapter, Gibson posits, “The coverage illustrates how girls’ relationship with popular culture is typically rewritten, excluding them from certain areas and containing them within others. In effect, girls’ culture is simultaneously criticized for ‘not going far enough’ and encouraged not to go too far” (2015, 27). She counters this attack on all sides that girls’ culture often faces by wielding a range of methods throughout—integrating feminist research on memory in the first chapter, historiographic accounts of the girls’ comics industry in the second chapter, and ethnographic analyses of female readership of girls’ and other comics in the fourth and fifth chapters. Within these frames, she allows for multiplicity, even-handedly considering often-conflicting positions, thereby showing that there is far more nuance in this subject that has been heretofore allowed. She deploys this tactic with particular deftness when analyzing the accounts of childhood comics readership that she gathers from interviews with over fifty women, showing not only that “there was not a monolithic set of experiences of the girls’ comic” (2015, 135), but also—through her intersectional analysis of issues of class, gender, generation, etc.—that there exists no truly unified experience of girlhood.

This technique of marshaling multiple perspectives is a hallmark of the evolving field of comics studies, within which Gibson’s work also belongs. Interdisciplinarity has been championed in recent field-defining texts like Charles Hatfield’s essay, “Indiscipline, or, The Condition of Comics Studies” (2010), and Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith’s anthology, Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods (2011), where over twenty academics consider comics from multiple disciplinary perspectives on matters of form, content, production, context, and reception. Given her wide-ranging approach, it makes sense that Gibson is a contributor to this anthology (2011), penning a chapter on the subject that she explores in greater depth in Remembered Reading. Her scope is also evident in special issues in the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics that she has recently co-edited, including “Audiences and Readership” (Weiner and Gibson 2011) and “Watch This Space: Childhood, Picturebooks and Comics” (Gibson, Nabizadeh, and Sambell 2014). These special issues and others she has co-edited demonstrate how her own research has the ability to nuance debate on a variety of topics—both within comics studies and in other fields, as her survey of disciplines in the third chapter conveys.

Alongside this breadth, the depth of her contributions to advancing research on British girls’ comics cannot be overstated. While she reveals that her work was initially hindered by the difficulty of obtaining the comics themselves, which led her to embracing memory and readership as her major approaches, her book facilitates future research in this area. In particular, her second chapter skillfully surveys the development of the British girls’ comics industry from the 1950s to the1990s, and she includes an appendix that lists over 100 girls’ comics titles and nearly 100 oft-remembered recurring stories in these titles, providing publication information and dates for these works. Overall, Remembered Reading is a masterful achievement on an underserved topic, supported by many years of research and varied approaches.

Reviewed by Margaret Galvan, City University of New York

Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of Birtish Girlhood

by Mel Gibson

Leuven University Press

Paperback / 272 pages / 2015

ISBN: 9789462700307

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on November 9, 2016.

References

- Chapman, James. 2011. British Comics: A Cultural History. London: Reaktion Books.

- Gibson, Mel. 2011. “Cultural Studies: British Girls’ Comics, Readers and Memories.” In Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods, edited by Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan, 1 edition, 267–79. New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, Mel. 2015. Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood. 1 edition. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Gibson, Mel, Golnar Nabizadeh, and Kay Sambell. 2014. “Watch This Space: Childhood, Picturebooks and Comics.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 5 (3): 241–44. doi:10.1080/21504857.2014.943013.

- Hatfield, Charles. 2010. “Indiscipline, Or, The Condition of Comics Studies.” Transatlantica 1.

- Kearney, Mary Celeste. 2006. Girls Make Media. 1 edition. New York: Routledge.

- Kearney, Mary Celeste. 2009. “Coalescing: The Development of Girls’ Studies.” NWSA Journal 21 (1): 1–28.

- Lipkin, Elline. 2009. Girls’ Studies: Seal Studies. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press.

- McRobbie, Angela, and Jenny Garber. 1976. “Girls and Subculture.” In Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain, edited by Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson, 209–22. London: Harper Collins.

- Smith, Matthew J., and Randy Duncan, eds. 2011. Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods. 1 edition. New York: Routledge.

- Weiner, Robert G., and Mel Gibson. 2011. “Editorial.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 2 (2): 109–11. doi:10.1080/21504857.2011.629668.