An introduction to our special feature on Rurality in Europe.

In the EU, 44 percent of the total land expanse is considered “rural,” with an even higher percentage in EU-N13 member-states (thirteen most recent). In a few countries―Slovenia, Romania, and Ireland, for example—the majority of the population is considered to be rural.[1] Moreover, an increasing number of Europeans now dwell in hybrid, intermediary, and liminal spaces where the very notions of rural and urban are challenged, such as the peri-urban, suburbs, peripheries, or urban villages. In spite of these statistics, the “rural” has been rather absent from European Studies. In the June 2020 issue of EuropeNow, I asked “Where is the rural in European studies?” Based on the observed dearth of papers presented on rural topics at Europeanists’ generalist conferences, I pointed to the stark invisibility of the rural as object of study in European Studies and the apparent void in rural research among Europeanists.

In spite of a favorable terrain for a productive cross-pollination and the existence of a few active organizations grounded in specific disciplines―such as the European Rural History Organisation (EURHO)[2]―few research agendas seemingly emerge explicitly at the intersection of European studies and rural studies. This special feature is an attempt at remodeling disciplinary epistemologies and tasking the field of European studies to remedy this lag. It seeks to encourage a more engaged representation of rural areas and rural populations in the study of Europe and to interrogate how interdisciplinary rural scholarship and its interconnecting realms of inquiry can help frame key questions about contemporary Europe that transcend the boundaries of the rural. Through their respective examinations of a particular rural topic, contributors in this feature not only delve into specific and often place-based issues, but also help to delineate new research paths that disrupt established assumptions in European studies, showing that the rural matters in seeking solutions to the always shifting global challenges today’s Europe faces.

The purpose of this collective effort is not to cover the innumerable relevant issues pertaining to rural Europe, but to position the rural on the map of European studies, anchor it in Europanists’ research agendas, and highlight it as a possible nexus where interdisciplinary and specialized research domains converge. Additionally, as it questions the validity of the habitual rural-urban dichotomies, the special feature aims to debunk a vision of rural Europe that is divorced from the urban. In opposition to the city, too often the rural is perceived as a static, passé, lagging-behind, and nostalgia-driven space that is bounded through a public imagination overly focused on emotions, quaintness, and pretty landscapes (the so-called rural idyll). Instead, scholars, artists, and NGO officers come together here to portray a rural reality different from that monolithic vision, one that is plural, multi-shaped, dynamic, inventive, in flux, based on varied local histories and contexts, relational, interconnected, and often transnational. The pieces included in the feature underscore the many social, political, and artistic undertakings being carried out in the rural in sync with the great quandaries of the contemporary world and contributing to addressing them.

Is the customary rural-urban dichotomy useful in a spatially hybrid Europe?

Several contributions in this feature tease out the nature of “rural,” what and who constructs it, how it might converge with or diverge from “urban,” and with what consequences on people and places. In his article on rural Crete, Aris Anagnostopoulos discusses the rural-urban divide as a cultural norm on the island and how villagers conceive of their own ruralness within an ambiguous political context, where the rural is at the same time valued for its past and its hyper-modernity potential. Angela Cacciarru points to important historical issues of access to land in Italy to explain how agrarian reform has shaped class relations between landowners and renters since the post-war period―a key moment in the transformation of the rural in Western Europe―showing that, within apparently same spaces, different rurals are rooted in differentiated impacts of legislative and economic policy―whether national or international (such as the Marshall Plan)―and uneven rights to resources. Also looking through a historical lens and starting in the same time period as Cacciarru, Gesine Tuitjer tells the story of a research project that took place in stages over several decades in Germany. Her article highlights the ways in which the rural is constructed also by those who study it and that the idea of the rural co-evolves with the choices made by scholars over subject matters, theoretical approaches, and methodologies. Her piece is an eye-opener into the role of the researcher in shaping an object of study in the long-term. It is also efficient in underscoring the necessary plasticity of the scientific inquiry that must echo the demands and compelling social questions of its time. Finally, focusing on the rural Netherlands, Twan Huijsmans analyzes whether an urban-rural divide can be measured by identifying political attitudes. He exposes the incidence of cosmopolitan vs. nationalist worldviews by juxtaposing urbanization index with attitudinal measurements such as Euroskepticism levels and acceptance of minorities. His results uncover that while it is clear that rural spaces are increasingly mutable and heterogeneous and that the urban-rural spatial binary categorization has become problematic in many instances of social, political, and economic life, where urban and rural can no longer be mutually exclusive, there is indeed a widening of a rural-urban gap in the Netherlands. Although he suggests that more conclusive intra-spatial analysis involving additional factors of spatial socio-demographic composition may be needed to compensate for these aggregate results lacking scalar refinement, the conclusions drawn are indications of important socio-cultural trends.

Rural as creative space: from renewed agriculture to the arts

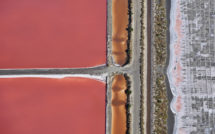

The second theme of this special feature focuses on the ways in which European rural areas are part of innovative Europe. Although agriculture is still a crucial component of the rural economy in some countries, rural areas for the most part have become multi-functional. No longer entirely restrained by productivist pressure, rural areas have taken on new roles as spaces of consumption, tourism, and leisure. Tom Mordue et al. explore the conflicts that can arise when a normative apprehension of landscapes runs into sustainability goals in Northumberland. His article unveils how the windfarm clean energy industry collides with attachment to place and points to the incompatibility of legislations occurring at different levels of governance. In Mordue’s study, the productive and aesthetic values of the rural landscape find themselves at odds. Conversely, art photographer Magali Chesnel demonstrates that this tension does not always have to be. In her exhibit “Painting-Like,” the salt marshes of Aigues-Mortes and Giraud foster an alliance between material resource exploitation, striking visual impact, and emotion triggered by the layering of colors, palpable temporalities of sedimentation, and awe in the face of natural processes that defy the imagination. In many places, the rural remains a place where the land is envisaged as part of a productivist cycle. But even agriculture has ventured into new territories and displayed its innovativeness as it adapts to the problems of climate change and loss of biodiversity that shape our relationship with natural and rural areas in the twenty-first century. Recent EU food and farming Eurobarometer statistics revealed that 95 percent of Europeans think that agriculture and rural areas are important for our future, 80 percent think that the EU is fulfilling its role in ensuring food security, and 76 percent believe that the Common Agricultural Policy benefits all citizens. In this special feature, Wyn Grant, Elizabeth Jones, Michaela and Arielle DeSoucey, and Evy Vourlides participate in a roundtable on “Changing Agriculture in Rural Europe” to highlight some of the ways in which food and wine producers are attempting to refashion the sector to be more holistic, more inclusive, and greener in the context of a changing Common Agricultural Policy that mirrors sustainability exigencies dictated by wider European platforms. These new EU agendas are increasingly championed by networks of activists, who, in their critique of late capitalism, are constantly putting pressure on the EU to abide by environmental ideals. The book review by Tracey Heatherington of the edited volume Food Values in Europe contributes to this conversation by casting light on how food movements are “coalescing around human rights and social justice, health and food safety, and finally, sustainability and environmental impacts.”

Finally, the rural must not be seen in isolation from cultural trends. Two pieces in the feature look at complementary aspects of the innovative cultural encounters taking place in the rural. Corinne Geering looks at the ways in which rural crafts have long been part of global markets and how the rural has diffused its culture outward through the circulation of local commodities and know-hows, generating emulations and imitations at a distance through “transregional transfer of ideas and practices, the mobility of objects and people, and the connections forged between them across the globe at the turn of the century.” On the flip side, in his interview, Ralph Lister explains how the world of culture is invited into the rural through touring projects and how the performing arts can transcend themselves by breaking urban boundaries in the search for new publics. As artists develop meaningful relationships with rural dwellers, art-making recovers a deep social function that may no longer find an effective expression conduit in the city.

Rural as interdisciplinarity

One last theme in this special feature on rural Europe is the value of interdisciplinarity and the fruitful intersecting of different “studies,” from women’s and gender studies, to migration studies, or social movement studies. Last October 15 was “Rural women’s day” ―an opportunity to take notice that in Europe the share of farms managed by women ranges from five to 45 percent across member-states, with many more women participating in the rural economy as agricultural laborers or other roles in the rural workforce. Jeremy MacClancy’s and Victoria Brown’s articles forge an explicit connection between rural studies and women’s studies. MacClancy describes the role of women in the “Empty Spain” dynamic and how rural emigration is also shaped by gender issues and the ways in which women and their social and labor contributions have been understood and represented in rural Spain. Speaking from the “Plastic Sea” of the greenhouses of El Ejido, Victoria Brown explores rural antifeminism and “how the Spanish far-right draws on moral idioms of ‘equality’ to muster support for women’s erasure” and in doing so perpetuates the everyday violent exploitation and oppression of women as a class. Also interested in rural social movements, José Duarte Medeiros Ribeiro writes about peasant activism in twenty-first century Turkey, the ways in which AKP’s neoliberal developmentalism and authoritarian populism have shaped access to public resources in rural areas, and how resistance has organized in response.

Migration studies is another “studies” that creates an opportunity for fecund intellectually cross-pollination with rural studies. Positioned at the intersection of rural and migration studies, Ruth McAreavey shares her research on immigration in rural communities in Northern Ireland, collecting stories from workers in the agri-food sector, refugees, and asylum seekers. She shows how their experiences “are embedded in the socio-economic history of Northern Ireland, from which can be identified some of the perceived main challenges associated with migrants’ integration.” Also addressing the question of integration and migration is John Bowen’s book review of Britain’s Rural Muslims that conveys that rural Muslims are not only a diverse group, but that they are very much creative actors of their “rural fortunes.”

In this special feature, EuropeNow not only expects to convey the richness and variety of the scholarship on rural topics, but also to advocate that studying the rural is central to a better understanding of Europe as a whole. In recognizing that the rural is a place of hybridization and ambiguities, contributors to the feature manage to expand the confines of rural Europe to make it relevant for all Europeans and thus craft new horizons and new futures for European Studies. It has been a very rewarding experience working with this collective. I am grateful for their engagement and commitment in times of great struggles. Beyond COVID-19, during the making of this issue, authors here faced devastating fires at their doorstep in the western United States, loss of electrical power after a rare meteorological “medicane” phenomenon, storm-induced flooding, and even―to end on an optimistic note—a new baby. Braving all obstacles, this dedicated community of scholars is yet another evidence that there is a will for the rural in European Studies.

Hélène B. Ducros is a human geographer (PhD University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill). She studies lived space, place-making, attachment to place, and landscape change and perception. Her research has inquired into rural transformations and rural-urban dynamics through an understanding of heritage preservation. Her latest publications appear in The Routledge Handbook of Place (2020), where she looks at the intersection of public art and memory of place and in Les labels dans le domaine du patrimoine culturel et naturel (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2020), where she examines transnational networks of rural communities through place-based labelization. At CES, she chairs the Critical European Studies Research Network (@CESCritEuro) and the EuropeNow Campus and Research Editorial Committees.

Research

- “Whither the Rural? Reflections on Rural Landscapes in Late-Capitalist Crete” by Aris Anagnostopoulos

- “The Agrarian Reform in Italy: Historical Analysis and Impact on Access to Land and Social Class Composition” by Angela Cacciarru

- “Reclaiming Rural Skills: Crafts from the European Countryside in the Global Market” by Corinne Geering

- “Changing Ruralities in Germany” by Gesine Tuitjer

- “Immigration to Rural Communities in Europe: A Necessary Evil or a Transformative Social Process?” by Ruth McAreavey

- “The Urban-Rural Divide in Political Attitudes in the Netherlands” by Twan Huijsmans

- “Environment, Landscape, and Place in the Windfarm-Tourism ‘Conflict’” by Tom Mordue et al.

- “Where Are the Women in ‘Empty Spain’?” by Jeremy MacClancy

- “Of Feminazis and False Accusations: Vox, ‘Gender Ideology,’ and Backlash in Rural Spain” by Victoria Brown

- “Peasantry and Rural Social Movements in Twenty-First-Century Turkey” by José Duarte Medeiros Ribeiro

- “Creative Economy, Policy, and the Pandemic in Scotland’s Island Communities” by Siún Carden

A Roundtable on Changing Agriculture in Rural Europe

- Introduction by Hélène B. Ducros

- “The Common Agricultural Policy: An Overview” by Wyn Grant

- “With the Grain: Food Sovereignty in Europe in the Age of COVID-19” by Elizabeth Jones

- “Bottle Revolution: The Emerging Importance of the Wine Industry in South Moravia” by Michaela and Arielle DeSoucey

- “Practicing Regenerative Design in Greece” by Evy Vourlides

Visual Art

Interviews

Book Reviews

- Britain’s Rural Muslims: Rethinking Integration, reviewed by John Bowen

- Food Values in Europe, reviewed by Tracey Heatherington

A Roundtable on Maastricht University Student Research

- Introduction by Patrick Bijsmans

- “Post-Political Populism as the Elephant in the Room: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Greta Thunberg’s Public Speeches on Climate Change” by Dominik Schmidt

- “Women “Going Native” During the Early Victorian Age: The Case of Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (1776 – 1839)” by Johanna Hvalic

- “Delegating, but How? A Comparison between the EU and the UNFCCC as Principals in Public Climate Finance Implementation” by Kirstin Herbst

Campus Monthly Round-Up

Editor’s Pick

References:

[1] For details on typologies, see Eurostat Methodological Manual on Territorial Typologies, 2018 Edition https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/9507230/KS-GQ-18-008-EN-N.pdf/a275fd66-b56b-4ace-8666-f39754ede66b

[2] For more information about EUHRO, visit https://www.ruralhistory.eu/

Published on November 10, 2020.