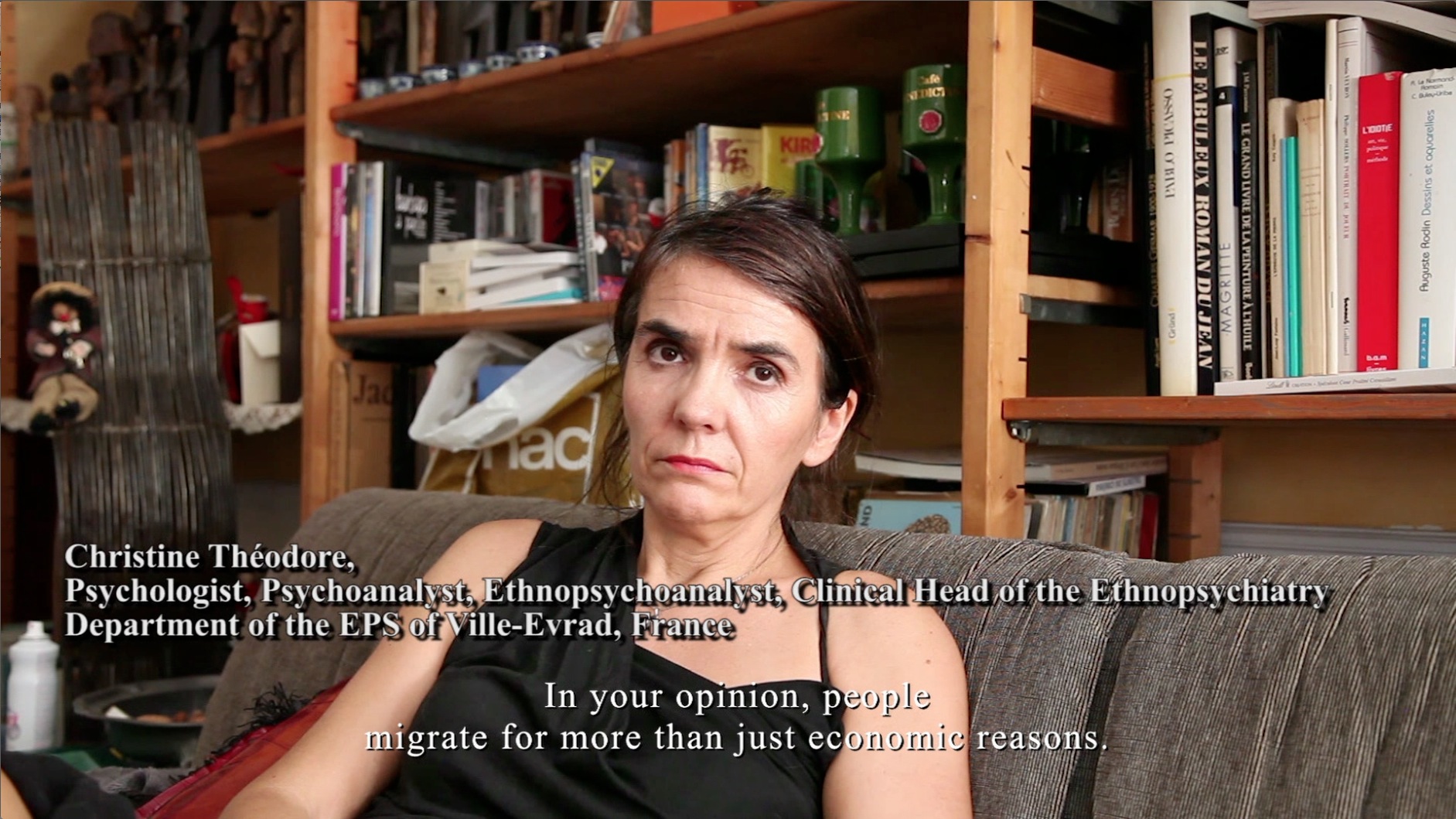

Kader Attia In your opinion, people migrate for more than just economic reasons. What do you mean by that? It’s an interesting point.

Christine Théodore Well, I think that the journey is hard, and if you look at people’s backgrounds, you can see they have problems with social skills, with how they function among other people. These people all have a different story, and we’ve seen that it’s not natural for them to follow certain rules.

I can think of one particular case; it’s not a clinical example but an assessment I made. I assessed a young woman who lives near here. A very pretty woman from Senegal, five foot nine, wearing a miniskirt, really beautiful, who said she had been the victim of an attempted rape. It happened on rue Mirat at two in the morning. She went to this guy’s place on the pretext of fixing his TV decoder. He was a bit drunk, they lay down on the bed, he tried something, she fought back, and the guy didn’t get what he wanted. But what happened had badly affected her.

I usually meet with people three times to talk with them. This young woman’s father had a significant social status and had a lot of authority over her. She’d had her first child before she was married, then she got married according to her country’s tradition. She experienced it as gang rape. This woman was not resigned to accepting tradition, when, for example, on the wedding night everyone waits outside the bedroom door …

This young woman arrived in France claiming it was to pursue her studies, but we realized that she left her country to escape her situation, and she bears the weight of her country’s tradition on her shoulders. She talked of experiencing an attempted rape in France, a modern country. If I hadn’t questioned her three times and talked to her for a long while, her story would have sounded like a case of true rape. If another woman had ended up in the same situation, she wouldn’t have reacted like that, but this woman really experienced it as rape.

Madjid Belaid In my work, I personally do not adhere to this idea that there are pathologies which are specific to migration or caused by it. I often see that a lot of these people already suffered from psychopathological problems even before emigrating. Before the migrating process, a person is a part of a group or society, and people don’t tend to leave this group without a reason. It’s not a coincidence. Even if politics force people to be categorised, in my opinion it is not economic migration. They are seen as refugees, asylum seekers. I think the act of emigrating is related to personal ethical issues that these people are trying to resolve through exile. I am one of those who emigrated, partly because of my position in society, partly because of my roots. There are also cases where there is a lack of support or is isolation that these migrants must deal with when they arrive in France, their new home. The lack of cultural references, as well as the lack of a cultural and sociological model that they would have followed for years, especially if they are from a rural background, makes it so that they no longer have their bearings, and this can provoke certain disorders. And this imbalance may precipitate psychological decompensation and cause pre-existing disorders to appear.

Kader Attia With the political situation in the region and the conflict taking place on the Lebanese borders, do you treat any patients from Syria?

Resident Yes.

Kader Attia Are they suffering from delirium caused by politics or religion?

Resident Yes, hugely. There are a lot of Syrian refugees, mostly people who are suffering from depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as people in a state of delirium. These people were already ill in Syria before they arrived here. The delirium is mostly political; they feel persecuted by ISIS, the Syrian army. It has to do with politics rather than religion. We see more patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder than patients who are truly depressed.

Kader Attia Do you ever try to find out if these people really are persecuted by ISIS or the Syrian regime?

Resident Yes, of course. Plenty of times they are telling the truth. They are often truly persecuted, but if we assess their delirium, they tend to dramatise and exaggerate the reality. The majority have been evicted from their houses and their region, but they haven’t suffered oppression directly. In their delirium they go much further; they believe it is their duty to fight ISIS, take part in the conflict, to fight the occupying force. The delirium goes far beyond the reality. You have to remain objective, but it’s not that difficult.

Abdelhak Elghezouani It concerns workers alone, the subject of Tahar Ben Jelloun’s first book. It affects workers who migrate alone and experience extreme solitude because they’ve left their families, wives and children in their home country to come and work. These people often suffer from certain pathologies which sometimes turn out to be mental illness. We have had more cases of psychological suffering than mental illness, although some do suffer from mental disorders.

But we do often wonder if these pathologies are caused by migration or if they were brought on by the migrating procedure. The debate is ongoing.

Today, the situation for migrants arriving here in Switzerland is that there is a cultural, civilisational, social and family divide so great that they struggle to adapt. Adapting is even harder for this type of migrant because they haven’t been invited and there’s no room for them. There is no work, nothing. It’s even worse than it was for the immigrants who arrived in the 1950s and 1960s. Another thing we observe, in terms of how the mind works or regarding psychiatry, is that these people have travelled for six months, a year, two years, and they show an outstanding resilience and a capacity to withstand hardship. The arrival conditions make them decompensate, often developing an illness they wouldn’t have had in another context.

Kader Attia How?

Abdelhak Elghezouani One diagnosis is often cited, and I don’t personally support it: post-traumatic stress disorder. It makes it seem as if the trauma had taken place before they arrived, whereas in reality the trauma was triggered upon arrival. Migrants are extraordinarily resilient. Those who have left are the strongest of their group. Because they are capable of making plans for a future and they refuse the status quo that they are given. But it is the disappointment they feel upon arrival; the difference between the hope they had and the reality facing them is what makes them suffer. It’s how they are treated when they arrive that makes them sick, not what they have experienced in the past.

Madjid Belaid: Assistant psychiatrist, Ethnopsychiatry Department of the EPS of Ville-Evrad, France

Kader Attia Exile is a geographical notion, but it is also psychological. The Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish said, ‘We can be exiled in a foreign land, we can be exiled in our own country, we can be exiled in our village, home and bedroom.’ Have you diagnosed this ambiguous and omnipresent exile? Is it a pathology you see regularly here in your practice?

Madjid Belaid As for exile and the various degrees of it and how it is expressed in psychiatric practice, I am going to talk about the first exile I discovered as a psychiatrist, which is the exile of the psychotic patient. It is irrelevant whether or not the patient is a foreigner. Because of the situation he is living in, there is a fundamental lack of comprehension. The patient feels misunderstood when he is confronted with neurotypical people like you and me. The first form of exile I could describe is the exile felt by psychotic patients. This is somewhat related to the first question, which is to find out if the exile itself could be the source of pathologies. I would answer by saying exile is the result of a process. We can see similarities between the teenager locked up in his bedroom and the immigrant worker living in a migrant hostel who hasn’t managed to fulfil the duty to his family of finding a job and sending money back home. There is a big difference between the two.

To sum up, this first form of exile I encountered really shocked me and encouraged me, among other things, not to become interested in psychiatry but rather to persevere with this discipline. At the beginning you often wonder if you’ll continue to work in this field. It was encountering the psychotic form of exile that made me stay. For me, this is the greatest form of exile there is. We are alone against the world.

Momar Gueye I think that this notion of exile you are talking about is something we often see. One of my predecessors, Professor Diop, did some interesting work on this concept, mentioning the uprooted Africans that end up in another country, confronted with other cultures, in particular in Paris. Diop explained how these people managed to reorganise themselves and tried to adapt to a new society. Exile or emigration is something that is sometimes difficult to live with, especially when you must adapt to a new context. When you arrive in a new society, you have to adapt. We can see that some immigrants try to shut themselves in a cocoon, keeping to themselves and living in groups, forming communities. As you said, some of them feel forsaken in their daily lives. This is why, for good mental health, we need to be integrated in a social group. When you say that we can even be exiled, I think this is very close to schizophrenia. Lots of African authors have said that schizophrenia doesn’t exist in Africa. I believe the opposite: it exists, but society’s tolerance is such that certain behaviours that might be considered pathological are sometimes tolerated by the social group. People with mental illnesses are not systematically hospitalised. Everyone knows there’s always the village lunatic in African villages. This man would stay with the group, and he would not be systematically labelled and hospitalised anywhere specific like a psychiatric clinic. Everyone would know that his behaviour was a little off, but the social group would see it as something that was part of us, that we couldn’t get rid of but rather learn to live with.

Abdelhak Elghezouani The syndromes or sets of symptoms that we can see in most of our patients have already been interpreted in psychiatry, but this doesn’t take into account the patients’ experiences, because the victims, these refugees who come to our country, have other more pressing problems. They don’t experience the symptoms described in psychiatry handbooks.

They have other forms of suffering, like nostalgia for what they’ve left behind, for their family, their land, their hometown, their friends. For everything they’ve left throughout their journey. These journeys go on and end in disaster. We’ve all heard about migrants drowning in the Mediterranean, others in Morocco and Spain. Tens of thousands of people have drowned, and the same number again or more have died on the roads, on the roads that leave from Senegal or Eritrea to Libya, from Afghanistan to Turkey or Greece. One of the reasons for their suffering is that they have witnessed death. The pain that they are feeling is because of the tragedy they have lived through.

Kader Attia (b. 1970, France), grew up in both Algeria and the suburbs of Paris, and uses this experience of living as a part of two cultures as a starting point to develop a dynamic practice that reflects on aesthetics and ethics of different cultures. He takes a poetic and symbolic approach to exploring the wide-ranging repercussions of Western modern cultural hegemony and colonialism on non-Western cultures, investigating identity politics of historical and colonial eras, from Tradition to Modernity, in the light of our globalized world, of which he creates a genealogy.

For several years, his research focuses on the concept of Repair, as a constant in Human Nature, of which the modern Western Mind and the traditional extra-Occidental Thought have always had an opposite vision. From Culture to Nature, from gender to architecture, from science to philosophy, any system of life is an infinite process of repair.

In 2016, Kader Attia founded La Colonie, a space in Paris to share ideas and to provide an agora for vivid discussion. Focussing on de-colonialization not only of peoples but also of knowledge, attitudes and practices, it aspires to de-compartmentalize knowledge by a trans-cultural, trans-disciplinary and trans-generational approach. Driven by the urgency of social andcultural reparations, it aims to reunite which has been shattered, or drift apart.

Recent exhibitions include The 57th Venice Biennial, “Sacrifice and Harmony,” a solo show at Museum Für Moderne Kunst, Francfort, “The Injuries are Here” a solo show at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux Arts de Lausanne, “Culture, Another Nature Repaired,” a solo show at the Middelheim Museum, Antwerp, ‘Contre Nature,’ a solo show at the Beirut Art Center, ‘Continuum of Repair: The Light of Jacob’s Ladder,’ a solo show at Whitechapel Gallery, London, ‘Repair. 5 Acts’, a solo show at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, ‘Construire, Déconstruire, Reconstruire: Le Corps Utopique,’ a solo show at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Biennale of Dakar, dOCUMENTA(13) in Kassel, ‘Performing Histories (1)’ at MoMA, New York, and ‘Contested Terrains,’ Tate Modern, London.

Kader was the recent recipient of the 2016 Prix Marcel Duchamp, France’s most prestigious art award.

Published on October 2, 2017.