This is part of our special feature, The Gender of Power.

Adua, the titular character of Igiaba Scego’s Adua, does not lay claim to her name. Her identity—and the very crux of her appellation—are ruled by the people designed to love her. The novel begins in an impoverished state in Somalia before Adua finds a permanent home in Italy. The men who occupy the years of her life are Zoppe, the father, and the husband she nicknames “Titanic.” Scego’s close examination of these relationships—mirrored in the divergence of their control—is framed against an urgency for autonomy. Both men, introduced to us at the beginning of the novel, immediately offer the dichotomy through which Adua’s narrative evolves. Of her father, she states, “To me, my father was ‘the one who brought me into the world’ or ‘the man who impregnated my mother’ or ‘the person who tore me away from real life’” (20). Of her husband she is similarly removed: “My husband, the boy I married, I never talk to him. I don’t even know why we got married. He was a Titanic, someone who’d risk drowning at sea to come here…” (21). With her heightened disconnect emerges all of the ways in which her men have failed her; apathy she uses to deflect a myriad of disappointments.

Before Zoppe, she was raised by a man she identifies as “papa” and a mother she calls “mama.” Her mother, known as “Asha the Rash,” died in childbirth. On the day Zoppe comes to claim them, Adua resists, asserting that papa is her father and mama is her mother. The emotional weight that is attached to these names—Asha The Rash, mama, papa, Titanic—is a singular way in which Scego allows the characters to place meaning to the people who are unknowable to them. Zoppe, the most unknowable, immediately becomes a dictator. It is in Adua’s desire to escape for a better life that she finds herself tacked to the tyrannical oppression of others in the most dire circumstances. The distinct pattern in this repetition is that Adua’s gender provides her with the deepest repression.

Italy, Adua tells us, is freedom:

“I wanted to dream, dance, fly. I wanted to escape. Italy was everywhere in my life. Italy was kisses, holding hands, passionate embraces. Italy was freedom. And I so hoped it would become my future” (67).

Scego skillfully encapsulates Adua’s independence to a country—the irony lies in the country, a place laden with fascism. But this Italy does not exist in Adua’s mind. Adua dreams of a place where the taboos surrounding sex, romantic idealism, and uninhibited aesthetic pleasures are not censored or damned. Her idealistic portrait of Italy is what drives her into reckless stardom. Her film, Femina Somala, is a box office success in 1977. She tells us about her director Arturo and his wife Sissi, a controlling and abrasive woman who appropriates Somali culture. She dresses Adua in traditional Somali clothing, perching her on a plastic baobab; “like Jane from Tarzan” (112).

It is Sissi who wants Adua “at all costs;” (113) who continues to degrade Adua to a “negress” whose long arms she touches in flight, signing fascist songs to her as they fly from Somali to Italy. Adua describes her assault with a particular regard for detail—her Italy does not equate to freedom. Adua is wasted, cold, aware that they are after her body (116). Sissi, the puppeteer, demands Arturo undress her: “‘Arturo, she’s yours, do whatever you want with her,’ Sissi said in a hard military voice that froze my blood” (118). We can hear the brittleness in Sissi’s voice; the way it stills Adua inside. The moments that follow are violent, removing Adua from herself. What is most compelling is not the gratuity of the scene, but the fact that it is Sissi who orchestrates the rape. Other men will touch her, but it is striking that in this first assault, a woman forces Adua open. A woman controls the heat of Adua’s blood. What Scego does here is unnerving, but it speaks volumes: Arturo, passive and unremarkable, is the director of a prominent film. Sissi is his wife, and in an industry at a time where women were not afforded those same opportunities as men, she finds ways to measure her own brand of sovereignty. If Arturo is given public glory, then Sissi sulks between shadows, playing conductor where she can. In a narrative where the women struggle to regain some semblance of independence, Sissi breaks through the glass ceiling in a manner that is truly horrifying, corrupting a young girl in order to rupture through the paralysis placed on her gender. For Adua’s part, the assault she endures follows her through the duration of filming, and Somali continues to seep into her life.

There are subheadings in which Zoppe speaks to Adua. Entitled “Talking-To,” these sections span the duration of the novel, and in these sections Zoppe criticizes every vein of his daughter. One section describes the genital mutilation he imposes on Adua without empathy or regret:

“Now you’re free, Adua, just think about that. You don’t have that damned clitoris that makes all women dirty. Snip, it’s gone, finally! Thanks be to God. The pain will pass. The pain is momentary. Whereas the joy of this liberation, Adua, endures” (84).

His deliberate control of her sex and the callous way in which he refutes her pain is perhaps the most obvious example in the text of a man suppressing a woman—here, he literally hacks away at her femininity, cutting the cord of her womanhood. The irony is this notion that he has somehow freed her, a conviction that feels even grimmer when we remember that Adua desires nothing but her independence. Later, when she is forced by Sissi to open herself to Arturo, the stitches that hold her amputated body are exposed. In a rare moment of profound assertion, Adua tells her story: “They do it to all the girls in my county. They cut our siil, the part that hangs down” (118). Then, there is a reference to scissors. She is cut apart, again, but nothing about the unraveling of her stiches feels liberating At her point of violent penetration, her hymen is forced from her, too, and nothing in her biology belongs to her. She is cut and sewn; ripped and maimed over and over again, slowly losing every inch of her being. Soon she has nothing of herself, reduced to cheap stardom and neglect.

Later, when Adua has aged and is left with her memories, she still faces subjugation. Scego skillfully rounds the narrative, ending Adua’s story at the same place it began. She looses her turban while with her husband, and it is then symbolically torn by a bird. A seagull picks at the fabric until it is too damaged to repair. Rather than appease Adua’s distress, her husband declares, “You looked terrible with that dull rag on your head. Right over there, at Habshiro, they sells scarves from the Emirates, the latest fashion. Now my wife will be beautiful and chic too” (168). Adua laments that it was her father’s turban. She reflects on the strain of her relationship with Zoppe, mourning years of turbulent grief. The turban, she maintains, represents her slavery. Her shame. The yoke she chose to “redeem herself.”

Further sections that stem from Zoppe’s point of view give us insight into his remorse. There is some mending between them, empathy and regret that is felt before and after his death. Despite the nuances that define her relationship to Zoppe—to her husband, and Arturo, and Sissi—some solace is found. These moments depicting pain soon followed with redemption are sometimes slight, as simple as the remorse felt over broken cloth. Or they angle over decades, the years fraught with pride. Some sympathy is found for Zoppe, but the bulk of our grief is felt for Adua. The girl who is stitched and cloaked. There are moments, too, (although they are few and far between) where she finds herself at the mercy of herself. She exudes a subtle autonomy when she speaks of her mutilation; or when she touches on her past, articulated with a dimension of detachment that is made of absolution rather than regret. Scego does not feed us these nuances. They are salted into the prose, through Adua’s telling of her life. They are between the lines, intricately weaved into a nostalgia that is not romantic, but potent in mourning.

Ultimately, Adua is a product of her time and her homeland and in the repressed duality of both things. We examine the will in her survival; a strength she harnesses. What the novel is, then, is an ode to that survival. The ways in which Adua resists the limitations placed on her gender; the first place she calls home. Repeatedly she fails; in different countries, in different homes, but she tries. Unabashedly she tries.

Yasmin Roshanian holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia University. She is currently writing a novel surrounding a family of Iranian immigrants. She lives in New York.

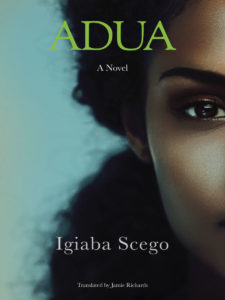

Adua

by Igiaba Scego, translated from the Italian by Jamie Richards

Publisher: New Vessel Press

Paperback / 185 pages / 2017

ISBN: 978-1939931450

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on July 6, 2017.