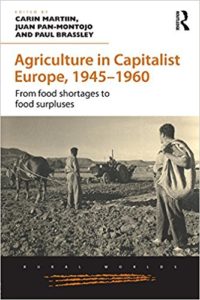

Agriculture in Capitalist Europe, 1945-1960: From Food Shortages to Food Surpluses Edited by Carin Martiin, Juan Pan-Montojo, and Paul Brassley

This is part of our special feature Facing the Anthropocene.

This book aims to address a gap in scholarship on European rural history. Specifically, it tackles a dearth of academic work on the emergence of modern agriculture in Western Europe, which occurred rapidly following World War II. The temporal focus in these collected chapters on the years between 1945 and 1960 also coincides with a dramatic transition from post-war food shortages to a situation of food surplus. In pursuit of its aims, this book hoped to answer three key questions: why changes in agriculture which occurred after World War II were so different to changes which took place after World War I; how, if and why technical and structural change happened; and why policies in support of agriculture were so common and how effective these policies were. This highly complex area is examined through a variety of lenses, not only social, political, and technical, but also economic and structural, and this approach was certainly successful in achieving the aims of this edited collection.

Agriculture in Capitalist Europe is organized around four themes, each addressed by three chapters. In Part 1 (International Politics), Juan Pan-Montojo opens the section with an explanation of the rise and evolution of international organizations and institutions, which facilitated post-war agricultural change in Western Europe. The next chapter, written by Emanuele Bernardi, explores the role of the European Recovery Programme (the “Marshall Plan”) and the Cold War on post-war agricultural development. This section is completed by González Esteban, Pinilla, and Serrano’s examination of international agricultural markets in this period. Together, the three chapters in this section provide a clear and detailed snapshot of the political context affecting agriculture in this period.

The first chapter in Part 2 (Market Regulation) centers on Greece, with author Scorates D. Petmezas exploring the productivist turn in Greek agriculture and the market measures impacting this. Britain is the geographic focus of the next chapter, in which John Martin examines the status change from food shortages in 1947 to food surpluses in 1957, and the role that various administrations may have played in this. The third and final chapter in this Market Regulation section is by Thomas Christiansen, who writes on his native Denmark, explaining that the situation there with regard to food supply was quite different to the rest of Western Europe. The juxtaposition of diverging geographical market contexts in this section successfully reveals the complexity of post-war European agricultural modernisation.

Part 3 (Technical Change) begins with Auderset and Moser’s account of the evolution of moto-mechanisation in European agriculture, with a particular focus on the role that draught animals played. Agricultural change in the context of both Iberian countries’ dictatorial regimes is the subject of the following chapter (Lanero and Fernández-Prieto). The relatively slow spread of tractorization in France is the topic of the final chapter in this section, with the author Herment, explaining this was due to a number of very practical and pragmatic barriers. This third section works well to elucidate how technical change happened differently in different parts of Europe, depending on underlying social, political and economic contexts.

Part 4, on Rural Society, begins with Karel and Segers examination of the different approaches taken by Belgium and the Netherlands to post-war agricultural challenges. Gesine Gerhard, in the next chapter, charts how Germany transformed its food system in a short period of time, and without conflict among the farming population. The third chapter in this section, written by Carin Martiin, provides an account of the sharp decline in Swedish farm labour and rural dwellers after World War II. This final grouping of chapters work together to reinforce the notion that a high level of state involvement lead to the successful restructuring of the countryside in four Northern European countries.

Despite bringing together work from a diverse group of authors, this collected edition manages to achieve cohesion. Each chapter presents a different perspective on post-war agriculture from the devastating food shortages in Greece (Chapter 5) to food surpluses in Denmark (Chapter 7) and Sweden (Chapter 13). The shifting focus across chapters on different jurisdictions and the approaches taken to agricultural modernization therein make for a lively and interesting read. Beginning with examinations of the international political context in Part 1 provides a strong grounding for considering the findings presented on market regulation (Part 2) and technical change (Part 3), and the effects these had on rural society (Part 4). In bringing together this research, Agriculture in Capitalist Europe has managed to identify common threads running through the measures adopted across Western Europe. One chapter that I found particularly engaging was Juri Auderset and Peter Moser’s examination of Mechanization and Motorization. Their focus on the role of draught animals as natural resources and how the use of “organic motors” (146) created tensions with the notion of an ever growing economy was thought-provoking.

While the notion of modernization of agriculture is central, there is no mention of the sustainability implications of this shift. Granted, the effects of this on rural populations are given adequate attention in the final section, but the ecological implications of intensifying agricultural production through the use of synthetic fertilisers, moto-mechanisation, the removal of hedgerow habitats and selective breeding, and of increasing food exports, are never mentioned. However, I understand that this is a work of history and not one of environmental studies, and that such an approach is beyond the purview of this work. The same comment could be made about my second criticism: while the Common Agricultural Policy is mentioned briefly here and there, there is no explanation of what exactly CAP is, and why it may be relevant. It seems remiss for even a short paragraph on CAP to be absent from the conclusion of this book.

It is surprising that the topic of an entire continent transitioning from a situation of food shortages to food surpluses in a matter of fifteen years should have been so neglected to date, which makes Agriculture in Capitalist Europe an important text to address this gap in knowledge. In addition, it is a valuable historical text per se, in that this review of the past helps bring greater understanding on how to deal with the current extraordinary political context that we face (CAP reform, free trade agreement negotiations (TTIP, CETA), Brexit and the presidency of Donald Trump), and how this may affect food supplies in Europe.

Reviewed by Brídín Carroll, University College Dublin

Agriculture in Capitalist Europe, 1945-1960: From Food Shortages to Food Surpluses

Edited by Carin Martiin, Juan Pan-Montojo, and Paul Brassley

Publisher: Routledge

Hardcover / 280 pages / 2016

ISBN: 9781472469656

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on May 2, 2017.