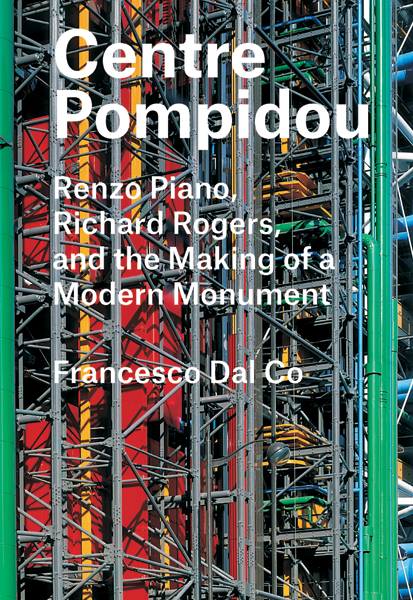

Centre Pompidou: Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and the Making of a Modern Monument by Francesco Dal Co

This is part of our special feature on Tourism: People, Places & Mobilities.

This handsome book is a notable first contribution to the new Yale University series “Great Architects/Great Buildings.” In his illuminating preface Dal Co begins with Virginia Woolf’s essay, “How One Should Read a Book,” published in the Yale Review in October 1926, where Woolf observes that a book is always “an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building.” Casting himself in the role of Woolf’s “fellow-worker,” he complements this approach with Walter Benjamin’s ideas about “the Italian style of argumentation,” invoking the plight of a “lost puppy;” and the powerful concept of “invented tradition” introduced by Hobsbawm & Ranger (1983). This leads him to the view that the invented tradition of the Pompidou Centre “has contributed not only to the building’s extraordinary success but also to an obfuscation of its real nature” (though “real nature” appears to contradict the author’s philosophy of historical research, which seems based on the idea of different narratives). Thus: “liberating Beaubourg from this invented tradition was one of my goals in writing this book” (Beaubourg is the area where it is located). The narrative evolves through six lively chapters, a portfolio of more than forty pages of spectacular photographs and drawings, and a ten page personal “Bibliographic Note” (a bibliography and an index would also have been welcome). The book is replete with excellent illustrations, political and architectural.

Chapter 1, “Paris 1968: ‘Reform Yes, Masquerade No’” refers to the infamous incident on 29 May 1966, when Georges Pompidou was Prime Minister of France and revolution was on the streets. President de Gaulle had fled to Baden Baden and on his return had proclaimed to his ministers (according to Pompidou) “La reforme oui, la chienlit [shit in bed/ dog’s dinner] non.” Pompidou became President in June 1969, and set about modernizing France and its economic and cultural institutions. In private, Pompidou had said that de Gaulle did not leave a monument. Dal Co, strangely, makes no mention of Mitterand (or the Mitterramses obsession) and his grand projets, which would have made an excellent comparison. With André Malraux (the minister of culture from 1959 to 1969) Pompidou set about creating a great center of culture in the context of what we could label competition for top spot in the hierarchy of global cities, in this case, Paris versus New York. However, Dal Co says nothing on the much-researched issue of global cities and their architecture, nor does he reference Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber whose book Le Défi Américain (The American Challenge, 1967), sold 600,000 copies in France alone, plus translations in fifteen languages. However, for architects and urbanists less interested in the socio-political backstory, these omissions will be more than compensated by the attention to fine architectural detail in this chapter as well as subsequent chapters.

Pompidou, Dal Co demonstrates, was a “man of culture,” as was his wife, interested in the historical embellissement stratégique (strategic beautification) of Paris in the tradition of Napoléon III and Haussmann. The market at Les Halles (built in the 1850s) a victory of tectonics (iron) over stereotomy (stone) and the principle of weight reduction, as in the Eiffel Tower prepared the ground for the Pompidou Centre on the site, despite hard-fought opposition from the traditionalists. Again, Dal Co fails to make an obviously interesting comparison with many other architectural icons, including the Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York – all were roundly criticized when they were being built, but all soon became unique examples of what is now commonly referred to as iconic architecture (see Sklair 2017). Dal Co seems totally oblivious to the now vast literature on iconic architecture and the related phenomenon of starchitecture (see Ponzini & Nastasi, 2016), but more about the significance of this later. The paradox that the beauty of Paris is the by-product of continuous changes may not be as unnoticed as Dal Co suggests, but the point is certainly valid for Paris and perhaps most other major cities. Learning from the traumatic events of 1968, Pompidou decided that the competition for the new building that would become the Pompidou Centre after his death would be open to all and that youth was no bar to success: the goal was an “architectural and urban ensemble that represents our time.”

Chapter 2 offers a meticulous chronicle of the main influences on those designing, engineering, and managing the building of the Pompidou Centre. The cast of characters is long and impressive: in addition to Piano and Rogers (hereafter P&R), Dal Co carefully credits Arup (including Structure 3, Ted Happold, Peter Rice), Lubetkin, Saarinen, Utzon, Frei Otto, Tange, Fuller; Banham, Sant’Elia, Vkhutemas, Makowski, Candela, Jenkins, the Fun Palace of Cedric Price/Joan Littlewood/Alastair McAlpine, Archigram, Newby, and Herron’s instant city. During construction the key input of Alan Stanton (leader of the team responsible for ‘non-programmed’ work) should also be noted. While P&R acknowledged the influence of Fun Palace and Archigram, Dal Co also notes their projects based on standardization and constraining construction methods. His conclusion is the conventional wisdom that the Pompidou Centre is a monument (though, as I argue below, “monument” may no longer be part of the conventional wisdom) for a society of consumption, with a pop aesthetic and the garish coloring of commercial advertizing to the fore. Dal Co attempts to historicize this by claiming that the “Centre Pompidou is like a gigantic arcade in the tradition of Parisian arcades,” the implication being that Walter Benjamin is “present as the inner essence of what has been” – another rather essentialist argument.

Chapter 3 addresses the contentious issues around the competition. Submissions were due by June 15, 1971 and the jury selected 681 projects for consideration. P&R, to their own surprise, were announced winners. It could be argued that Pompidou’s greatest practical contribution to what was to become the Pompidou Centre was the appointment of Robert Bordaz, the man who had organized the evacuation that ended France’s war in Vietnam, run the French version of the BBC, and the Cannes Film Festival. Georges Pompidou died in 1974 while still serving as President of France, and was succeeded by Giscard d’Estaing, not a “whole-hearted supporter,” who cut funding to the extent that, as Dal Co suggests, the completion of the project was in serious doubt. It is at this point in the narrative that Dal Co introduces his theory that the Pompidou is best regarded as an “involuntary monument,” mobilizing the words of P&R that the competition guidelines were too “formal and monumental,” the opinion of the jury (whose deliberations are pictured and dissected) that the project should not be a monument, and the Denkmalkultus (cult of monuments) theory of Alois Riegl (first published in 1928 and translated into English in Riegl 1998). While the Pompidou was being built, the director of its Department of Arts proclaimed, in the spirit of ’68: “We need to take the uniforms off the guards and the culture.” We might interpret this cynically in terms of the critique of “transparency” in architecture, which Fierro (2003) discusses in the context of the grand projet. This was in an environment when every major French city was to have its own Maison de la Culture. Inaugurated by Giscard d’Estaing in 1977, Dal Co sees the Pompidou as a pale shadow of the Maison de la Culture idea, a travesty of the aspiration that France could become the cultural leader of the world. He labels it a fetish (from Agamben), a monster (from Baudrillard), a building that has escaped its programme (like Frankenstein).

The concluding two chapters narrate the story of how, 250,000 drawings later, P&R rewrote the rules of architecture in France. This involves much technical discussion of the engineering challenges of the building, especially how Peter Rice solved the problem of the internal structure via the mighty gerberettes (floor trusses, the saddles or hinges, named for a German engineer in the 1850s) – another example of the maxim that the past never disappears from the present and the present is never free from the past. The main design compromise was that large luminous screens on the west façade (we could label them ‘“Archigramish” or “Fun Palatial”) were replaced with a long escalator – the famous tubes. Dal Co describes this as a rhetoric-free aesthetic. He notes that the Krupp logo was erased from the girders by Algerian laborers to appease opposition from nationalists. He also takes aim at the architectural profession in France, charging that unlike the “sketch architects” in the École des Beaux-Arts tradition of the “architect goes home early” (never getting involved with business) P&R were hands-on practice architects. Their “huge machine” was put together bit by bit, just like the original Les Halles. Dal Co dismisses criticism of the Pompidou in a leading French architectural journal (L’Architecture Aujourd’hui, 1977) by an assorted group of architects as “overlooking the true essence of the building” (more essentialism?) and proclaims: “I have devastating news for the aesthetes: Old Paris was once new” (after Karl Kraus).

Theoretically, this admirable book stands or falls (like many actual monuments) with its central idea, namely the “involuntary monument.” Monumentalism in architecture, it needs hardly be said, appears to be in terminal decline. Sociologically, the idea of iconicity is rapidly replacing it as the dominant trope, if not among high art architecture critics, but certainly among everyone else. If we define an iconic building as one that is famous (for a city, for a “nation,” or globally) and one that has aesthetic/symbolic significance (these two characteristics feed off each other) then I would argue, contra Dal Co, that the Pompidou Centre is an example of iconic architecture par excellence and that this designation tells us more about the building and the society in which it is located, than any kind of monumentality. This is still highly contentious within architecture, but is becoming less so for interested parties outside the architecture profession and most other cultural fields. Many major architects and architect firms designate their own buildings as iconic, and the term is now widely used to perform the theoretical and pragmatic tasks that were once the terrain of the monumental.

On a recent visit to the Pompidou, I picked up the official Map. In it the building is described in French as “un monument emblématique,” in English as “an iconic twentieth century monument.” In Milan, visitors to the Accademia Ambrosiana will see two plaques in the square, one in Italian and one in English – both referring to Icon Leonardo. And in Milan’s wonderful Novecento Museum exhibiting Andy Warhol’s “Last Supper,” Leonardo’s original is also referred to as “iconic” in the English, cellebrima in the Italian. Times are changing.

As the Pompidou triumphantly celebrates its thirtieth birthday, let me conclude by quoting the words of the architect Richard Rogers: “We said that we will put the building not in the middle of the piazza, but actually on one side because that will give people a place to meet… The idea was that you had a public space, and you’d go up the facade of the building in streets in the air with escalators floating across it, so the whole thing became very dynamic. People come to see people as well as to see art; people come to meet people. So we wanted to practice that as theatre” – surely more icon than monument.

Reviewed by Leslie Sklair, London School of Economics and Political Science

Centre Pompidou: Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and the Making of a Modern Monument

by Francesco Dal Co

Publisher: Yale University Press

Hardcover / 168 pages / 2016

ISBN: 9780300221299

References:

Fierro, A. (2003) The Glass State: The Technology of the Spectacle. Paris, 1982-1998. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hobsbawm, E. and Ranger, T. eds. (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ponzini, D. & Nastasi, M. (2016) Starchitecture: Scenes, actors, and spectacles in contemporary cities. New York: Monacelli.

Riegl, A. (1998) The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and its Origins. In Hays, K.M. ed. Oppositions Reader. New York: Princeton Architectural Press: 621–51 (translated by K.W. Forster and D. Ghirardo).

Sklair, L. (2017) The Icon Project: Architecture, cities, and capitalist globalization. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.