Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman.

Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman.

The captain was named Umrug. His life had started somewhat chaotically. His father, Choem Mendelssohn, was a bird, and his mother, Bagda Dolomidès, was Ybür.

Choem Mendelssohn and Bagda Dolomidès worked at the Brussovanian Colony, a forestry complex where they slaved away, he as a foreman for the logging area and she as a supervisor for timber shipments by water routes. As a bird, Umrug Batyushin’s father wasn’t appreciated by his bosses or by the convicts in the brigade under his watch. He repeatedly escaped falling trees that were somewhat suspicious and, twice when he had come back from an executive meeting to his house in the black of night, strangers had carried him away between the shacks and beaten him up, breaking his nose and teeth, shattering his ribs, and, finally, pissing on him. Bagda Dolomidès, Umrug Batyushin’s mother, complained to the authorities, objectively presented the facts as well as the medical reports and the X-rays clearly showing the broken cartilage and bones, but, in the absence of witnesses and motives for the crime, the investigation came to the conclusion that there had been a simple drunken brawl like the ones that broke out every day in this place, and the complaint didn’t result in anything. When Umrug Batyushin’s father was attacked a third time, he didn’t get back up.

Having buried her husband, Bagda Dolomidès decided to leave the hellish world of the complex and to seek her fortune elsewhere, even if that meant risking all the dangers of a flight through the taiga. She had more energy and steadfastness than Choem Mendelssohn, she could set aside her womanly weaknesses when she had to confront adversity, and she would have already left without a second thought if she hadn’t been caring for little Umrug Batyushin, who wasn’t capable of making any efforts or sacrifices himself just then. Umrug Batyushin was going on three years old, but he was rather sickly and wouldn’t have trotted more than a kilometer without trouble. He would have held his mother back if she’d dragged him along, holding his hand. Bagda Dolomidès bound him to her bosom, which was large, and she balanced her charge with a backpack in which she had put, aside from dried food, a pistol that she had filched from a guard after getting him drunk.

The taiga didn’t scare her; she was used to its contact, its smell, its oppressive darkness, its endlessness. She was an orphan and the people who had found her lived in a small outcrop surrounded by forest, where the inhabitants were, aside from the representatives of the authorities, mostly hunters and workers for sawmills, furniture factories, or logging companies. Then she had gotten transferred to the Broussovonian Colony where her contract specified that she had to stay a good ten years, and once again she lived very close to the trees and very close to the black limits beyond which the world changed, beyond which the world only obeyed the laws of vastness, twilight, and wild animals.

Right after bypassing the complex’s gates, she slipped past the first lines of pines, reached a cluster of larches, and immediately put as much distance as possible between herself and the Colony, which stretched out a great distance in every direction, but which had major gaps in its network of roads and pathways. She was counting on this weakness in the infrastructure to keep everyone from giving her trouble after her first day of walking and, for fifteen hours straight, she didn’t stop for even a minute to catch her breath. Umrug Batyushin sat quietly against her breast without whining. She hadn’t given him anything to drink before leaving so that she wouldn’t have to undo the straps to let him pee, and, realizing that in any case he was tightly strapped to his mother’s chest for the tedious journey, the little boy was steadfastly silent and slept as best as he could.

Eventually they had to cross several streams, ponds, and even shallow lakes, which Bagda Dolomidès knew the names of, because for years, having been put in charge of delivering wood by floating it down various waterways, she had constantly been studying her maps. The second day, she caught a fish close to Kuduk, another one close to Ulakhan. She didn’t meet anyone, she never heard dogs barking. It was the middle of summer and the wolves had gone hunting farther south. By Charang, after ten days of walking without any surprises, she was attacked by a bear. It reared up ten meters in front of her, showing its teeth with a throaty growl that didn’t leave any doubt as to its intentions. Bagda Dolomidès set aside her fear for later, didn’t lose her cool, and, while talking at the bear in a shrill voice that surprised it, she slipped her hand into her backpack, pulled out the pistol, and emptied the cartridge clip into the animal. It, more scared than wounded, took flight. Bagda Dolomidès couldn’t stand on her two legs anymore. She sat on the ground and breathed frantically for several minutes. Umrug Batyushin whined and sniffed beneath her chin. Bound against her as he was, he hadn’t even seen the bear.

The echo of gunshots reverberated deep into the silent forest, and it caught the attention of a small group of bandits. They, five of them, set eyes on her trail. They quickly surrounded her and, after collectively raping her, suggested that she join their group and go with them to a place called Mudugan where they had a base and where, according to them, she could safely leave the little Umrug Batyushin, such as when she went with them on expropriation raids or to assassinate local capi- talists. Bagda Dolomidès wasn’t taken with the idea of being the shared female in a group of robbers, and besides she knew nothing about this place called Mudugan that they had mentioned and which they bragged was calm and relatively comfortable, so she expressed reluctance and hesitated for several minutes. But since night was coming and Umrug Batyushin was still crying unhappily, and since aside from being criminals and rapists they seemed to be brave; she made the decision and followed them. Deep down she realized that in spite of what had been the best time to escape, the warmest months, she wouldn’t have managed to cross the taiga all on her own, and meeting these men seemed providential. She would never have said it out loud, for fear of giving over her allegiance so pitifully, but she suddenly felt that they had saved the two of them, the little Umrug Batyushin and her.

The group was made up of three young hotheads and two older men who had plenty of common sense. The older ones were in charge. They were fifty or sixty years old, and on their arms were tattoos in blue ink, with motifs of intertwined snakes, barbed wire, and faces of angelic girls like those that bandits had dreamed of for centuries. At night by the fire, they took part in gang rapes with the same loutish and morose energy as the younger ones. When they came to Mudugan, Bagda Dolomidès negotiated with them for periods of intimacy and rest, which they gracefully allowed her, since they were so happy to have found their base again, where they could finally wash and sleep without having to be on constant lookout. And besides, over the course of their days traveling in the forest, they had adopted her as one of their own.

Mudugan was a typical village of thieves, built in the middle of the forest in a gap that barely deserved to be called a clearing, so tightly did the trees encircle the log houses. There weren’t any paths that had been marked to get there and it was inaccessible to anyone who didn’t know exactly where the ravines and undergrowth were. That was where Umrug Batyushin learned to live his life as a self-sufficient child, there where he learned to shoot rifles, to carve up elk, and endure cold and hardship, as well as bear the howling of the wolves that were rare in the Brussovanian Colony’s area, but which every winter came right up to the house and prowled on the doorstep or sniffed the edges of the little windows once night had fallen. In the houses, not a lamp was lit after the evening meal, to economize and because the idea of staying awake by the wood-burning stove with a book in hand barely occurred to the bandits. However, there were a handful of books at Bagda Dolomidès’s place, souvenirs of fruitless expeditions to unlikely hamlets or encounters with unknown corpses, always inexplicably far away from everything. Aside from collections of official lyrical poetry, there were two manuals for Bordigist agronomy and a thesis on the application of egalitarianism in extreme climactic conditions or even after death, off-putting opuscules that couldn’t have intrigued anybody, but which allowed Umrug Batyushin to study his alphabet and learn a few new words. The little Umrug Batyushin heard the wolves clawing and whining on the other side of the wall and it never bothered him in the least. He was often alone, whether because his mother was keeping this person or that person company, or because she had left with the others for a raid. So as not to be found, the band did their work far away from its base, and Umrug Batyushin could easily end up the sole inhabitant of Mudugan for weeks without having to be on constant lookout. And besides, over the course of their days traveling in the forest, they had adopted her as one of their own.

Then there was an early summer marked by a long wait for the bandits to return, then a middle summer. The weeks went by. Eight, then nine. Umrug Batyushin had gotten sick twice after eating large and appetizing mushrooms from tree stumps, but, after several days of diarrhea, he got better. He ate hare meat, squirrel soup, crow soup. The days were interminable and he ended up filling them by haltingly reading the books that had taught him how to read. Aside from the swarms of flies and mosquitoes, a tiny audience gathered to listen to him, two or three furry caterpillars, several ants, sometimes a few fox cubs that still had everything to learn. From the doorstep of his cottage, Umrug Batyushin went back over the basics of what he knew. He taught lessons on the necessity of collective discipline in the tundra, he discussed the ways of eradicating the idea of individual profit when there was nothing but lichen to eat and the temperature was below negative forty Celsius. It was during one of these conferences that his existence changed. Uncle Ioura, the oldest of the thieves, broke past the first larches darkened and out of breath, then he said that the raid had gone bad, that self-defense militias had ambushed them, that all the others had been killed, including Bagda Dolomidès. And that, although he had shaken off his pursuers for about ten days, they had to leave Mudugan.

The oldest of the thieves had a sense of responsibility. He liked Umrug Batyushin, but he couldn’t hang onto him for the years to come; the boy’s training as a bandit hadn’t culminated yet, and besides, enough proletarian morality subsisted in Uncle Ioura’s heart for him to realize that the existence this child was promised could be something other than a suicidal mixture of taiga, violence, and illegality. Which is why, after having bundled up a rudimentary pack for the boy, he guided him through the trees to a fuel depot close to Yuunkiy-yur, where Uncle Ioura had once lived with his family. Crossing the trees took them six weeks and, when they knocked on the door of the old man’s distant cousins, the road had just been turned white by the autumn’s first snow. The old man greeted his parents, explained the situation to them in a few sentences, said good-bye to Umrug Batyushin, and went back into the forest.

From that day, Umrug Batyushin’s daily life and future changed dramatically. The fiftysomething couple he had been entrusted to comprised two excellent people, communists gifted with generosity and compassion. Although delighted by the prospect of safeguarding the future of a child who had fallen out of the sky like this, the two of them had enough common sense not to let him languish with them, cut off from the world and in the extremely limited environment of the gasoline distribution base at Yuunkiy-yur. Once they had established a proper relationship with Umrug Batyushin, and started to take visible pride that their adoptive son was well-versed in tundra ideology and official versification, they sent him to board at the secondary school in the nearest city, Somodiokh, which was easily accessible in the winter, when anybody could trundle on the river ice to cross the three hun- dred kilometers separating it from Yuunkiy-yur.

In Somodiokh, Umrug Batyushin, who could have failed school and been a hooligan given the way he had spent his formative years, became a model student. He was doubtlessly somewhat coarse and overly quiet, and his comrades saw him as someone who could slice up squirrels, imitate barking wolves, and describe the copulations between his mother and the bandits, but his teachers talked of him as a healthy and hardworking student, attracted to the natural sciences, certainly clumsy when he was justifying his enthusiasm for the Bordigist prin- ciples in agriculture, but able to recite by heart a certain number of paragraphs on basic dialectical materialism. When people teased him, about his assassinated bird-father, about his Ybür mother turned whore in the taiga, about his lawless uncles or his adoptive parents who stank of fuel, he only hit once, but so hard that the teasing stopped. After a test the semester after the fight, he earned the right to wear the Pio- neers’ Scarf, then the years went by, and as a mustache darkened his upper lip, he began to go to the Komsomol meetings.

Everything went well for him, and, one summer when he went up the river in a boat to embrace the two old Yuunkiy-yur communists, he told them that he had been admitted to a technical school in a department that would prepare him for a career in lumber, and then a professional career that would bring him back to the taiga. They were all overjoyed, his adoptive parents most of all, because now he wouldn’t just be useful to the society he was giving the best of himself to, but he could also move closer to Yuunkiy-yur, get hired at one of the various local lumberyards and, when he visited them at the fuel distribution base, receive their affection and moral and material support. The couple was starting to get old and, despite resisting every petit-bourgeois and egotistic tendency, wanted to have Umrug Batyushin nearby and dreamed of family meals, jars of mushrooms offered as they said their good-byes, lazy Sunday walks along the river between the warehouses and the tanks.

For Umrug Batyushin, a peaceful existence as a worker seemed preordained, but the global situation had gotten worse and, in the area as elsewhere, the consequences could be felt. People thought they had been crushed forever, but the enemy summoned up its strength, resurged everywhere, and had already turned into an ever more devastating cyclone. The Second Soviet Union headed full steam toward its collapse. The wars that had been dormant violently broke out again. The omnipresent nuclear power plants everyone had counted on to help do away with the State and give the most distant regions total energy autonomy didn’t fulfill their promises. Most of them broke down, creating immense strains on all five continents that nobody could even hope to clean. Unnerved by the prospect of humanity’s end, the populations lost all their loyalty to collectivism, and were seduced by all sorts of political monstrosities, if they provided even a slight contrast to their bleak present.

The Orbise called for help. Umrug Batyushin enlisted for its defenses at all costs, and instead of following a carpentry or logging course, he left with a volunteer regiment toward the capital, where he learned to handle weapons he’d never even heard of until then, learned to fight and to obey catastrophic orders without arguing, learned bitterness, learned to survive in the midst of bloody defeats, and, when the Orbise after decades of resistance collapsed miserably and he himself was killed, learned to wander through the irradiated zones and to go farther with the others, whoever the others were, and however far the distance remained for him to go before closing his eyes for good, or at least before finding concentration housing that suited them.

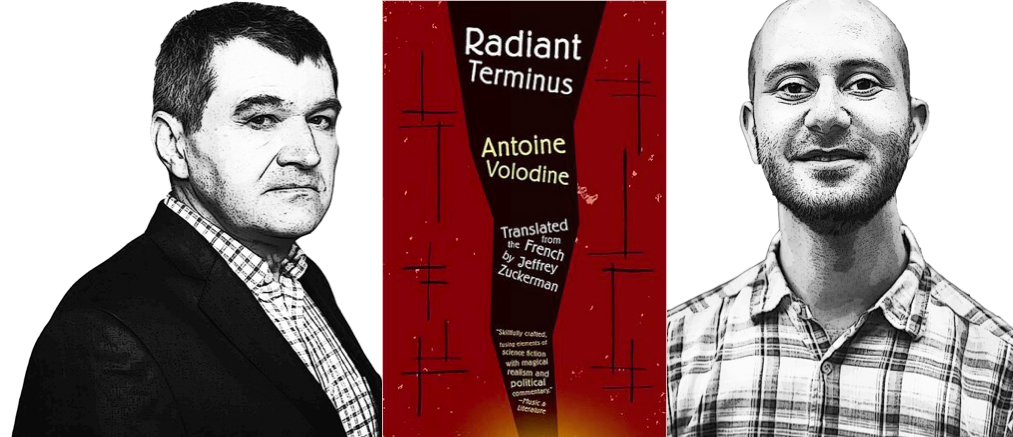

Jeffrey Zuckerman is digital editor of Music & Literature Magazine. His translations from French include Ananda Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins (Deep Vellum, 2016) and Antoine Volodine’s Radiant Terminus (Open Letter, 2017) as well as numerous texts by Marie Darrieussecq, Hervé Guibert, Régis Jauffret, and Kaija Saariaho, among others. A graduate of Yale University, his writing and translations have appeared in Best European Fiction, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Paris Review Daily, Tin House, and Vice. He is a recipient of a 2016 PEN/HeimTranslation fund grant for his translation from the French of The Complete Stories of Hervé Guibert.

Antoine Volodine (a.k.a. Lutz Bassmann, a.k.a. Manuela Draeger) is the primary pseudonym of a French writer who has published more than 40 books, over 20 under this name. Seven of his titles are currently available in English translation, including Minor Angels, Bardo or Not Bardo, and Post-Exoticism in Ten Lessons, Lesson Eleven.

This excerpt from Radiant Terminus is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2014 Editions du Seuil. Translation copyright © 2017 Jeffrey Zuckerman.

Photo: Antoine Volodine, Cultural Services of the French Embassy

Photo: Jeffrey Zuckerman, Authors & Translators

Published on January 5, 2017.